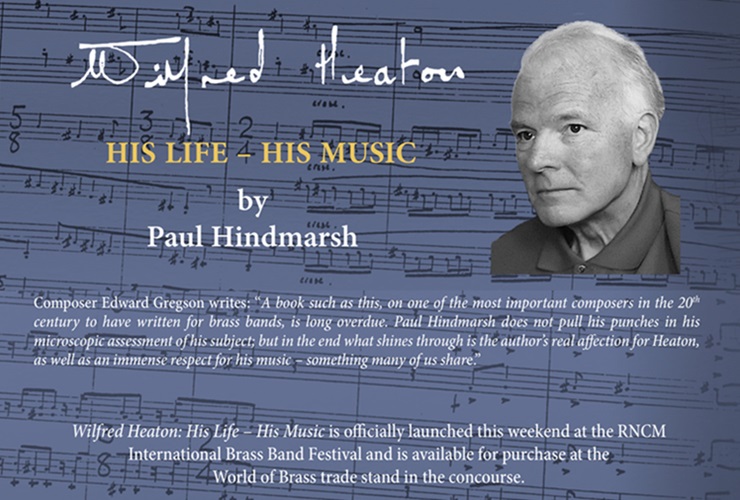

In the second of a four-part series of exclusive extracts from his biography of Wilfred Heaton, author Paul Hindmarsh explores the emerging years of the enigmatic composer.

2. The Apprentice Pieces…and all that jazz

“Jazz doesn’t do any good at all” (Bramwell Coles, 1925)

Wilfred Heaton was a studious teenager for whom ‘tooling up’ with the skills fit for purpose within The Salvation Army was a serious business.

That is not to say that the results of his labours were always serious in intent. The exuberant bravura of the cornet solo ‘I will follow Thee’ and the gentle bucolic air of two secular songs reveal a lighter side to his musical personality. His creative gifts had been identified by the musical gatekeepers at The Salvation Army’s Music Editorial Department before he left school. By the outbreak of war six years later he had composed most of the SA music now regarded in the brass band world as quintessential Heaton.

Bramwell Coles

From 1936 until 1952, discovering and nurturing gifted young musicians, “for the sacred charge of conveying their thoughts to the people (and) winning men for God,” was the goal of Bramwell Coles (below) in London.

Having recognised potential in Wilfred, Coles kept in touch with his family and encouraged the talented teenager to submit appropriate items.

He would write encouraging letters, or arrange meetings with promising writers, to discuss latest offerings. Having recognised potential in Wilfred, Coles kept in touch with his family and encouraged the talented teenager to submit appropriate items.

However, as far the Heaton family is aware, Wilfred never considered full-time ministry, unlike his sister. Hilda was accepted for training as an SA officer in 1939 and entered William Booth College in Denmark Hill, South London, just three weeks before war was declared.

Bumpy ride

In later years Wilfred described his relationship with Bramwell Coles as, “a bumpy ride, from my side at least.” This tension between them was rooted in matters of musical language. In his late teens Wilfred discovered contemporary music and jazz, about which the usually restrained Coles was completely dismissive.

“Jazz doesn’t do any good at all,” Coles said to the music critic of the Toronto Daily Star in 1925, during his time as the SA’s literary editor in Canada, adding, “Good music must have a moral purpose.”

All good music has a message, and I am not talking of jazz. Jazz has as much relation to good music as a tin can tied to a cat’s tail has to an organ in a cathedral

We can assume that he considered jazz immoral and its associations with night clubs, dancing and dance bands lacking in any spiritual value. Speaking at the SA’s Winnipeg Music Councils the following year, he opined that, “Our service as (SA) bandsmen is a mission, and we should regard it seriously and reverently and have a clear vision of our calling. All good music has a message, and I am not talking of jazz. Jazz has as much relation to good music as a tin can tied to a cat’s tail has to an organ in a cathedral.”

The freedom and spontaneity of jazz, the allure of blues and the syncopations of ragtime were clearly anathema to Coles, for whom the plain-speaking message of a hymn tune and the uplifting spirit of the march were more congenial.

First attempt

Hilda Heaton recalls Wilfred’s first attempt at a march, now long destroyed, was in 6/8 time, quoting the devotional song 'Take Time to be Holy'. “I don’t know whether (Coles) sent it back,” Hilda recalled in 2001, “but they told him that they couldn’t have a tune like that in a march.”

this second attempt, entitled simply ‘Praise’, was full of the syncopations of jazz and the sounds of the circus rather than the quasi-military conventions of an SA march. It did not go down well and was returned for revision.

Sometime in 1937, Wilfred tried once again. Taking his cue from the chorus popular at Sheffield Park, ‘Praise, O Praise Him’, this second attempt, entitled simply ‘Praise’, was full of the syncopations of jazz and the sounds of the circus rather than the quasi-military conventions of an SA march. It did not go down well and was returned for revision.

Praise

Wilfred recalled in 1971 that, “the original I sent to London was jazzier compared with the published version.” Without the original manuscript of ‘Praise’ as a reference, it is not possible to assess how deep the jazz influence penetrated. However, there are enough points of difference in the published version from the conventional SA march to suggest that the jazzy style must have been pronounced. The definitive version, eventually released in July 1949, has become a brass band ‘classic’– in effect the Heaton signature tune.

The definitive version, eventually released in July 1949, has become a brass band ‘classic’– in effect the Heaton signature tune.

Albert Jakeway (above) was the first interpreter of 'Praise' and a supporter of Heaton

Whether his 18-year-old self ever heard the jazzy original played by his father’s band before it was published is uncertain. This is possible as Hilda Heaton remembers her brother asking if their father could play a march through at band practice but, “Father didn’t really have his heart in it. I think this was because he didn’t want Wilfred in any way to get big-headed, but to keep him humble.” John Heaton was unbending in observing the SA rule that any unpublished music could not be performed without the permission of the SA’s International Music Council.

Coming of age

There was tradition in the Heaton family for the ‘coming of age’ 18th birthday to be marked with a gift of a gold watch. Wilfred asked if he could have a selection of music scores instead, reflecting a new enthusiasm for the rhythmically charged and brusque energy of the music of William Walton (1901-1983).

There was tradition in the Heaton family for the ‘coming of age’ 18th birthday to be marked with a gift of a gold watch. Wilfred asked if he could have a selection of music scores instead

How Wilfred discovered Walton (below) is unknown. It is unlikely that he went to the premiere of ‘Belshazzar’s Feast’ at the Leeds Triennial Festival (8th October 1931), but much more likely that he tuned into a BBC performance with Adrian Boult at the helm from London’s Queen’s Hall on the family radio. Study scores of ‘Belshazzar’s Feast’, ‘Suite No. 1’ from ‘Facade’ and ‘Symphony in B flat minor’ were all hot off the press.

Wit, parody and satire

We should remember that Walton, then just 35, was still an enfant terrible within the musical establishment. He courted controversy when Façade was first performed in 1923, with Edith Sitwell narrating her modern verse through a megaphone concealed behind a screen. Thus inspired, Walton revealed his own gift for wit, parody and satire, for which the pulse of popular dance, the flavour of the music hall and the spontaneity of jazz were fair game. The jazzy rhythms, blazing fanfares and brilliant orchestral colours of ‘Belshazzar’s Feast’ and the ‘Symphony’ were profound influences on the young Heaton.

The birthday gifts were put to immediate use and became effectively a new tutor book. Constant Lambert’s piano duet version of the first suite from ‘Facade’ was a favourite that he sought to emulate in a miniature suite for piano duet of his own to play with Hilda, entitled ‘Three West Indian Melodies’.

Resonated

In place of the popular songs and parodies of ‘Facade’, he chose three songs that were popular in the SA as children’s action choruses.

The impact of Walton’s music, both light and serious, was decisive and long-lasting.

This clearly resonated with Wilfred, who followed his example in his own writing, recognising that it was possible to be witty, jazzy and vivacious while still retaining the fundamentals of a traditional technique

Behind Walton’s facade of mimicry and satire was a traditional technique built on inherited European symphonic traditions, as his major orchestral, choral and film music reveals. This clearly resonated with Wilfred, who followed his example in his own writing, recognising that it was possible to be witty, jazzy and vivacious while still retaining the fundamentals of a traditional technique.

When Wilfred came to write on a larger scale away from the SA after the war, the Walton influence stayed with him, as the gestures and rhythms of an orchestral suite (later to become ‘Partita’) and the opening melody of ‘Sinfonia Concertante’ attest.

Bandmaster George Marshall conducting massed bands in London

Invitation

As his 20th birthday approached, Wilfred received an invitation from Bramwell Coles to write a short piece for brass sextet. Coles hoped to take it on a tour of North America, including a visit to the Star Lake Music Camp in the summer of 1939.

The quartet ‘Scherzo’ had been written with Wilfred and his SA friends in mind. Music for brass sextet was in effect his first commission, albeit unpaid, with the prospect of performances in the USA by some of the SA’s most skilled musicians. However, as the storm clouds of war gathered over Europe, the tour was postponed and with it any immediate prospect of a performance. The tour eventually took place in 1948, but without Wilfred’s piece.

With perhaps an eye on its intended audience, Wilfred chose to base his work on the verse of a famous popular song from the United States, ‘Oh dem golden slippers’, which Herbert Booth had turned into a gospel song which begins, ‘Oh, the Blessed Lord he saved my soul’. Wilfred brought all that he had discovered of jazz and of parody in the ‘lighter’ fayre of Walton to this exuberant miniature.

Toccata

The manuscript of ‘Music for brass sextet’ remained un-regarded until Wilfred transformed it into ‘Toccata, Oh the Blessed Lord for brass band’.

The core of the original is so characterful that a wholesale re-write was not necessary. A myriad of small adjustments to melodic contours, textures and harmonic profile bring its big-band credentials into sharper focus.

Mature voice

The most audible of the changes occur at the climax to the end of the first section and the addition of a ‘full stop’ final chord. In its final form it bears all the ingredients of Wilfred’s mature voice – ‘glint in the eye’ humour, ‘wrong-footing’ syncopation, unexpected harmonies and strong thematic foundations.

Its first performance by the International Staff Band under Bernard Adams, during a Songster Leaders’ Councils Festival (12th June 1971, Royal Albert Hall, London), was both a surprise and a triumph.

Its first performance by the International Staff Band under Bernard Adams (below), during a Songster Leaders’ Councils Festival (12th June 1971, Royal Albert Hall, London), was both a surprise and a triumph. In this context it still appeared strikingly modern.

Thirty-four years earlier, precisely what Coles was expecting Heaton to deliver is unknown. It is safe to assume that something short and simple with a narrative derived from familiar hymns or SA songs would have been welcomed. What Coles received was daring in its originality for any era of SA music, not just the 1930s.

Too advanced

The ‘cut’ of the themes and the audacious ‘neo-classical meets jazz’ presentation of material must surely have mystified the SA’s Editor-in-Chief. 'Music for brass sextet' was too advanced and Praise too jazzy, but Coles nevertheless recognised Wilfred’s gifts. The simpler songs – ‘The Army’s Marching Song’, ‘On the Road’, the male voice item ‘Marred for me’, and the anthem ‘Our Glorious King’ – had already found their niche in The Musical Salvationist.

Perhaps as a young Salvationist composer’s ‘response to just criticism’, the next offerings provided the useful music with a message that Coles was looking for. Sometime shortly before the outbreak of war, Wilfred submitted a trio of devotional items, one in each of the conventional forms. The first was a selection of SA songs entitled 'Passing By', the second a setting of the 19th century hymn tune 'Martyn' (by American presbyterian minister Simeon Butler Marsh, 1795-1875) – both are modest, functional, but fluidly constructed arrangements.

Complete apprentice

The third work was the Meditation 'Just as I am', which is more ambitious in treatment – arguably Wilfred’s most complete apprentice piece.

Many years later, he gave an account of the circumstances surrounding its inspiration. It related to a weekend ‘campaign’ which the International Staff Band undertook at Sheffield Citadel SA in the city centre.

The third work was the Meditation 'Just as I am', which is more ambitious in treatment – arguably Wilfred’s most complete apprentice piece.

The Sunday evening meeting at Sheffield Park finished early to enable those who wanted to go down Park Hill and hear the ISB’s ‘wind up’ performances. Wilfred arrived early while the congregation was still at prayer. A small gathering was grouped around the Mercy Seat. In conversation with Alan Jenkins for a 1995 Brass Band World feature article, Wilfred recalled being “taken by the fervour” of their singing of Charlotte Eliot’s poem ‘Just as I am without one plea’ to the much-loved tune by William Bradbury (1818-1868).

Courting

Making the short trip down Park Hill to Sheffield Citadel after the Sunday evening meeting was by no means a rare event, as Wilfred was courting a songster at the Citadel, Olive Mary Fisher. She was four years older – quite an age gap in those days – and also a piano pupil of May Bennett.

“Dad knew Mum was the love of his life,” Wilfred’s youngest daughter Ingrid recalls, “and he felt this very strong connection as soon as he met her.” Their relationship blossomed, but any thought of marriage was put on hold until Wilfred had completed his apprenticeship at Cocking & Pace.

Eric Ball and the SP&S Band - the first to play through a Heaton piece in 1938

Tools of life

At the same time, he had been working to equip himself with the requisite tools for a life as a professional musical craftsman. Already a published composer for SA bands and songsters, much was expected of him in the future within the ‘Army’ organisation. He had composed many of the pieces that once published became enduring favourites in The Salvation Army and eventually beyond.

Wilfred was all too aware that being an articled craftsman, without the opportunity of further study at music college, was going to be a hindrance to the full realisation of his wider creative ambitions,

His cornet playing was much admired wherever he was invited to play. At Sheffield Park his creative touch at the piano delighted and moved the small congregation in equal measure. Gaining an LRAM at 18 for his piano playing was a measure not only of his proficiency and musicality but also of his capacity for hard work.

Wilfred was all too aware that being an articled craftsman, without the opportunity of further study at music college, was going to be a hindrance to the full realisation of his wider creative ambitions, as was his total lack of contact with the musical world beyond The Salvation Army.

However, all thoughts of his future as husband, professional musician, composer, or articled craftsman were put on hold when, at 11.15am on 3rd September 1939, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain fatefully declared, “This country is at war with Germany.”

Paul Hindmarsh

Wilfred Heaton His Life - His Music (Part 1)

https://4barsrest.com/articles/2024/2092.asp

Extracts from Wilfred Heaton: His Life – His Music by Paul Hindmarsh

PHM Publishing & Production, available from: https://www.worldofbrass.com/102200

Price: £30.00