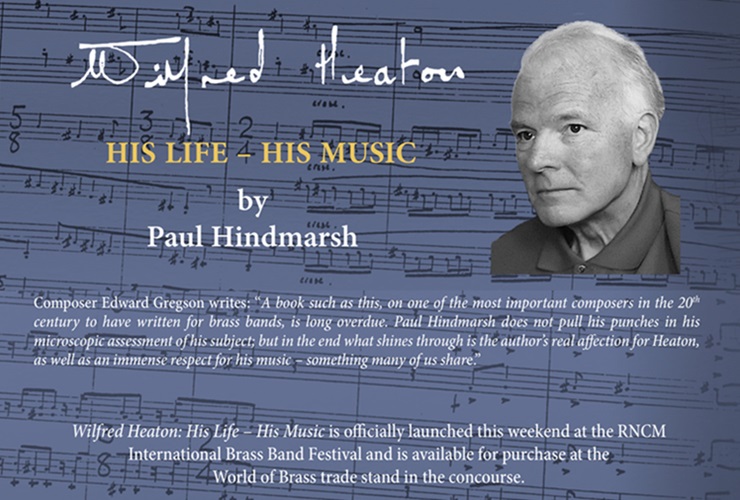

Paul Hindmarsh’s much-anticipated biography of the composer, conductor, pianist and teacher Wilfred Heaton (1918-2000) is launched on Friday 24th January at the RNCM International Brass Band Festival in Manchester.

Over 15 years in the making, 'Wilfred Heaton: His Life – His Music' charts this unique composer’s creative struggles, from youthful impulse and instincts to a life-changing decision to call a halt to serious composition in his mid-30s to his decision to compose again, in his 70s.

These extracts from the biography, follow Heaton’s early life from childhood in The Salvation Army at the Sheffield Park Corps until his initial encounter with the writings of Rudolf Steiner that at the age of 29 were to transform his life.

1. Sheffield and The Salvation Army

“I had a strong urge towards composing music since childhood.”

“I can’t remember a time when I didn’t want to compose,” confessed Wilfred Heaton in what turned out to be our final telephone call towards the end of March 2000.

His reflective mood had been prompted by a determined effort to finish what is arguably his most personal and certainly his longest opus, 'Variations for Brass Band'. He had not attempted anything as substantial as this from scratch since the early 1950s and had all but completed a draft short score when we spoke. There was a sense of relief in Wilfred’s voice that this task had been achieved after almost a decade of struggle.

I suppose the creative instinct never really leaves you

His next statement was even more intriguing. “I suppose the creative instinct never really leaves you,” he said. There was a question in his inflection, but the telephone conversation ended on this ambivalent note.

He died 10 weeks later with many questions raised by this chance remark left unanswered.

Strong urge

In 1997 Wilfred drafted a long letter to Howard Snell, whose persuasive powers had led him to end a long creative silence some years earlier. In it he reflects how difficult he had found over a long life, “to rationalise, let alone justify [my feelings about] the whole compositional thing. I had the strong urge towards composing music since childhood, and it did not begin to diminish until my early thirties when I encountered Rudolf Steiner’s Anthroposophy.”

This encounter was to prove life-changing, the catalyst for an extended period of “drastic personal re-orientation.”

As he confessed in one of many notes scribbled to Howard Snell on a page of the Variations sketch, “I lost the impulse to compose. Such activity seemed to be unimportant compared with the spiritual impulses provided by Steiner.”

Wilfred experienced an increasing tension between composition and total immersion in Steiner’s spiritual philosophy that, “seemed to dry [me] up.” As he confessed in one of many notes scribbled to Howard Snell on a page of the Variations sketch, “I lost the impulse to compose. Such activity seemed to be unimportant compared with the spiritual impulses provided by Steiner.”

Youthful ambition

Wilfred’s youthful ambition had been to compose full-time. He worked with diligence to acquire the skills and musical breadth to realise it.

His gifts as writer, cornetist and pianist were recognised early in The Salvation Army, through which he became a published composer at the tender age of 14. His creative gifts, which he regarded as God-given, were nurtured within the protective embrace of the Sheffield IV (Park) Corps where his large extended family worshipped. It was no surprise that much was expected of him given the talent that was soon to emerge.

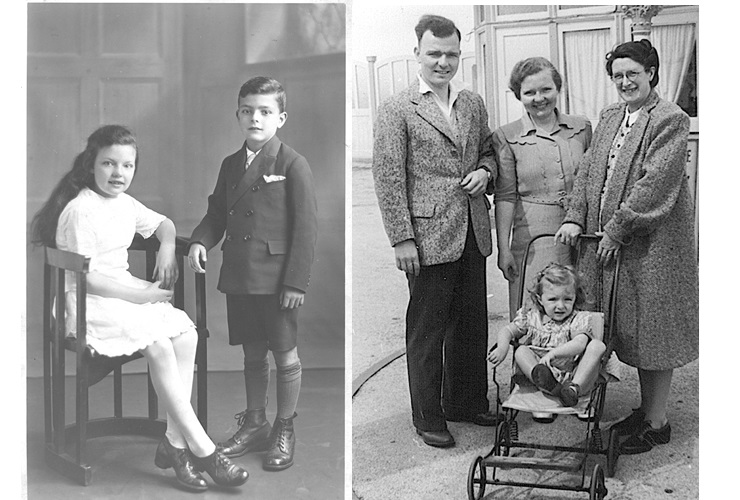

The Heaton family: With his sister Hilda and in 1948 (right)

John Wilfred Heaton was born on 2nd December 1918 in the family home, a terraced house in Blagden Street in Sheffield’s Park Hill district.

Park Hill was the poorest district of the city – a compact area of a few densely populated lanes around Duke Street, just over the brow of Park Hill from Sheffield Midland Station. Wilfred’s sister Hilda Heaton (1916-2012) remembered their little terrace dwelling as …a two-up, two-down house, with toilet up the yard and no bathroom of course. Bath time was every Friday night in front of the coal fire.

Everything was done in the one downstairs room; the boiler for the washing was there in the corner, then the sink and the big mangle and you were at the door. My father used to sit in the armchair in the corner by the fire. We only went into the sitting room, the front room as we used to call it, when we had company. We were always shivering because it 14was never given a chance to get warm. [Hilda Heaton, 2001]

Different

Wilfred and Hilda were brought up in the aftermath of the First World War and during the Depression, but they were sheltered from the worst of their deprivations by parents John and Miriam, and the wider Christian family of Sheffield Park Corps. Other than Sundays at the ’Army’ or Young People’s Band practise time, Wilfred was rarely to be seen out in the lanes playing with the other children. He would be upstairs reading, writing or practising. He already appeared ‘different’.

Wilfred was rarely to be seen out in the lanes playing with the other children. He would be upstairs reading, writing or practising. He already appeared ‘different’.

Another reason for this isolation was his delicate health. Infant mortality in Park Hill was the highest in the city. Wilfred often revealed his feelings of being ‘set apart’ to his youngest daughter Ingrid, who was something of a kindred spirit.

We talked non-stop really from when I was a teenager. Dad was passionate about his music right from a child, but he was often ill. Auntie Hilda called him 'sickly' and his mother and Grandma Heaton were very protective of him. He nearly died when he was quite young, and they didn't think he would survive. I remember him saying to me that at school he wished he could be like all the other boys, but he knew he wasn’t. And he wished he could be good at sport and always felt a bit of a weakling. He felt set apart from his peers, because his interests were so different from anybody else’s – about music and spiritual things – particularly from about 10 or 11. [Ingrid Lihou, 2012]

Musical genes

Wilfred and Hilda both inherited their uncle Richard Rawlins’s musical genes. He was one of the original ‘missionaries’ sent from Sheffield Citadel to establish the Park Corps in 1883. They shared a love of music and of spiritual matters, both of which were encouraged at home and within the extended SA family. Wilfred’s first cornet teacher was his uncle Freddie Rawlins, the Young People’s Band Leader. From the age of eight, Wilfred practised hard on the cornet and especially the piano. Both Hilda and Wilfred went to Mrs. May Bennett for piano lessons.

Wilfred’s first cornet teacher was his uncle Freddie Rawlins, the Young People’s Band Leader. From the age of eight, Wilfred practised hard on the cornet and especially the piano.

Also a Salvationist, Mrs. Bennett worshipped at Sheffield Citadel in the city centre, where she accompanied the Songsters which her husband directed. Under her maiden name, May Fantom, she enjoyed a successful teaching practice in Sheffield, with many local SA children among her pupils.

Hilda remembered her as, “an excellent pianist and a very good teacher for the piano, but she was a bit like we all were, ‘blinkered’ Salvation Army-7wise. I think the only reason we went to her was because she was in the Army.” It wasn’t long

efore Wilfred was writing down music of his own.

Earliest piece

Among his manuscript collection is a hymn tune, 'Norwich' – after the street on which the family lived. This is the earliest piece of Heaton that survives. He made such speedy progress that his father acquired an old upright piano. Even as a schoolboy, he seems to have set his sights on composing and arranging music suitable for publication in the SA’s range of brass band and choral journals.

Among his manuscript collection is a hymn tune, 'Norwich' – after the street on which the family lived. This is the earliest piece of Heaton that survives.

When he was 12, Wilfred composed a choral song entitled The Army’s Marching Song. May Bennett wrote the lyric. It is a bright, toe-tapping march, remarkably assured in its harmony and part-writing.

First publication

John Heaton proudly sent it off to the influential Head of the SA’s Music Editorial Department in London, Lt. Col. Frederick Hawkes, in the hope that it would be published. Hawkes was the first point of contact for any prospective contributor to a series of subscription-based journals. Wilfred recalled in conversation with Kenneth Downie that Hawkes sent “a charming letter” in return.

In May 1933 this lively little song appeared in an edition of The Musical Salvationist. At the age of 14 Band Lad J.W. Heaton had become a published composer within the Salvation Army system. This was just the beginning of what he hoped might be a life dedicated to composition.

Confident

In August 1932, with The Army’s Marching Song accepted for publication, 13 -year-old Band Lad Wilfred Heaton was confident enough to submit his next piece to Frederick Hawkes himself.

Wilfred “put together” a substantial air varié solo for cornet and piano based on the hymn 'I will follow Thee my Saviour'. It is a much more ambitious work than the little marching song. As it remained in manuscript, we can assume that it did not pass muster or was not deemed suitable as a solo with piano.

Whether permission was sought by John Heaton for Wilfred to play it himself from manuscript is not known, but unlikely. Hawkes filed the manuscript in what was to become a substantial collection of Heaton manuscripts over years to come. Although the location of many of them is now unknown, this one and the accompanying letter eventually came into the possession of composer and editor Kevin Norbury in the 1990s, when the SA’s Music Editorial Department was reducing its vast accumulation of manuscripts prior to relocation.

Future

When Wilfred turned 14 a decision had to be made regarding his future. He had passed the examinations necessary for him to follow his sister from Park Junior to Park County School next door, but money was always tight. John Heaton would not have been able to send both his children to secondary school while also paying for the music lessons he wished Wilfred to continue.

Hilda Heaton recalls. I went to the county school – not called a grammar school – but a pretty good one. And Wilfred could have had a place. But at that time there wasn’t much money going around. Wilfred was having money spent on his piano lessons with May Bennett and on harmony and counterpoint through correspondence with Bandmaster George Marshall and a local teacher. He was also going privately for cornet lessons with another local man, Mr. Grieve. My parents felt that I could have the advantage of going to the secondary school, where we had to pay for everything at that time, and Wilfred could have the advantage of the music. They made a wise choice. [Hilda Heaton]

Apprenticeship

As for employment, John Heaton decided that the security of a skilled trade was best for Wilfred. After one false start with a lens maker in Paradise Square, he eventually secured a music-related apprenticeship round the corner in Paradise Street at Cocking & Pace Ltd. This was a small, well-established maker and repairer of brass band instruments.

After one false start with a lens maker in Paradise Square, he eventually secured a music-related apprenticeship round the corner in Paradise Street at Cocking & Pace Ltd.

The owner’s son, Herbert Cocking (b.1935), was brought up above the shop. He became Wilfred’s apprentice in 1950 and was taught in exactly the same way as his father had taught Wilfred, to enable him to execute, “all types of work from a minor repair to the stripping-down and rebuilding of any instrument from trumpet to tuba.”

“Wilfred never really wanted to be an apprentice,” Cocking adds. “He was only interested in music. He just wanted to compose.”

An apprenticeship towards any skilled trade was not a path he would have chosen for himself. “Wilfred never really wanted to be an apprentice,” Cocking adds. “He was only interested in music. He just wanted to compose.”

This was confirmed five decades later in conversations between Wilfred and brass band composer Kenneth Downie: “He told me that he’d always wanted to write music – and by that he meant make a living as a composer – an ambition which he held fundamentally.”

It seems obvious, with the benefit of hindsight, that working as an instrument repairer was not the most appropriate occupation for this precociously gifted young musician.

Paul Hindmarsh

Extract from Wilfred Heaton: His Life – His Music by Paul Hindmarsh

PHM Publishing & Production, available from: https://www.worldofbrass.com/102200

Price: £30.00