On 1st September 1924 the British Open Championship changed forever.

As the world was getting used to seeing the first ever newsreel coverage of potential US Presidential candidates, a group of confident young Australians, with wooden chairs tucked under their arms, walked onto the King’s Hall stage at Belle Vue in Manchester to perform ‘Selection from Franz Liszt’ arranged by Thomas Keighley.

Out of the arc

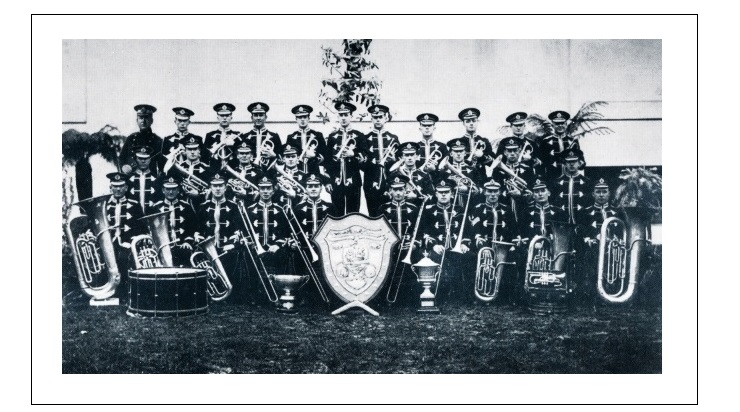

Sat in an arc formation like an orchestra in front of their conductor Albert Baile, the Newcastle Steel Works Band from New South Wales in Australia was on the cusp of being crowned 72nd British Open Champion.

After they played not even the soon to be announced news of the assassination attempt on Italian dictator Benito Mussolini or Malcolm Campbell setting a new land speed record of 146 miles per hour would cause a stir of such startled surprise – or for that matter, deflated hubris.

It was a stunning victory, made even more memorable in that much like their cricketing counterparts in winning the first ‘Ashes’ urn in 1882 on British soil, they were also presented with what was to become an iconic trophy (above).

It would be almost 30 years later that another non-British band would emulate them (the National Band of New Zealand in 1953), and over 90 until one from Europe (Valaisia in 2017) did the same.

It was a stunning victory, made even more memorable in that much like their cricketing counterparts in winning the first ‘Ashes’ urn in 1882 on British soil, they were also presented with what was to become an iconic trophy (above).

Enthusiasm not excellence

In 1924, few brass band supporters could even contemplate that the cream of British contesting champions could be beaten by colonial counterparts. Australian banding, unlike that in New Zealand, was thought of as being based on ex-pat enthusiasm rather than indigenous excellence.

Very little was known of the Newcastle Steel Works Band itself ahead of their six-month trip to represent Australia at the 1924 British Empire Exhibition at Wembley. The second-hand whispers were certainly not enough to frighten the crack ‘northern’ bands such as Wingates, Besses, Black Dyke Mills, Harton, Creswell and South Elmsall who dominated the Belle Vue prize list at the time.

Australian banding, unlike that in New Zealand, was thought of as being based on ex-pat enthusiasm rather than indigenous excellence.

Company grant

The band was formed in 1916 when workers at the giant BHP steel plant in New South Wales (above) developed a musical interest. They were helped in their endeavours with a company grant of £50, sufficient to purchase second hand instruments.

They soon began to thrive. Progress was first made under conductor J J Kelly, who emigrated to Australia from England in 1917, and from 1920 by the legendary figure of Albert Baile (1882-1961).

He had enjoyed success with Perth City Band, and soon after his appointment brought five of its players with him to Newcastle. It was the catalyst that soon saw them win B Grade and then A Grade New South Wales contests.

Motherland

Baile was determined though to make a mark far from home shores and by 1923 the ambition was to travel to the brass band motherland. Fund raising soon began, but their aim was finally met when they were engaged to perform at the 1924 Empire Exhibition in London - the six-month tour to be managed by George Porteous who had organised the antipodean legs of the famous Besses o’ th’ Barn world tour of 1906 - 1907.

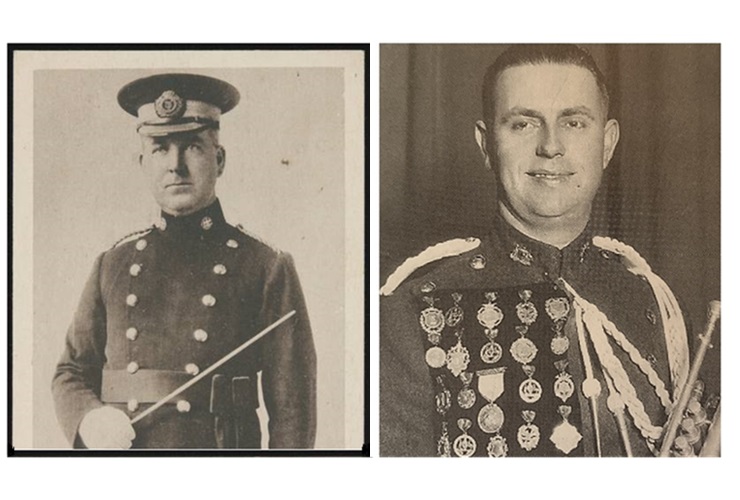

Baile (above) was under no illusion that his band required further strengthening - with the signing of Arthur Stender, (above) the outstanding Australian cornet player of his generation the key. With him on board others were persuaded to take the trip of a lifetime, although there were soon mutterings of well-known solo champions being ‘engaged’ simply to play secondary parts in some sections.

Grudging admiration

Soon after arriving in London the band toured the Midlands and the north of England, attracting large, curious crowds.

That soon changed to grudging admiration, and then, no little amount of fear, especially after they competed in a contest in Halifax where they beat a high quality field of rivals, including Black Dyke Mills, Foden’s Motor Works, Irwell Springs and Crosfields.

That soon changed to grudging admiration, and then, no little amount of fear, especially after they competed in a contest in Halifax where they beat a high quality field of rivals, including Black Dyke Mills, Foden’s Motor Works, Irwell Springs and Crosfields.

Word was out, and soon debilitating cases of ‘Australitis’ were being reported having been caught by some leading bands ahead of their appearance at the September British Open. Black Dyke Mills decided not to compete, stating they were “not fully prepared”. 1922 winner South Elmsall was also missing.

Darker mutterings

There were also darker mutterings that the Australians were not playing ‘fair’ - especially as the British Open rules stated that; “Every member of a band must be resident in the town or within a distance of 4 miles or thereabouts of the town from which the Band is entered’.

British Open rules stated that; “Every member of a band must be resident in the town or within a distance of 4 miles or thereabouts of the town from which the Band is entered’.

Stender was also deemed by many to be a ‘professional’, having “been engaged” to perform with the band.

The Australians cared little about the ‘whinging poms’ and were fighting fit – rehearsing the test-piece (which has been made available to the bands in the July) between their Exhibition performances (and they were giving up to three a day).

The winning formation

Monday 1st September (the Open was held on a Monday until 1938) dawned misty and damp, a hangover from one of the wettest summers of the century. Despite the chill, the Newcastle players were happy with their draw – 15th of the 16 contenders who had to impress the adjudication trio of Dr Thomas Keighley, Jesse Manley and Harry Muddiman.

Despite the chill, the Newcastle players were happy with their draw – 15th of the 16 contenders who had to impress the adjudication trio of Dr Thomas Keighley, Jesse Manley and Harry Muddiman.

Although they had already sat in formation at previous contests, the audience at the King’s Hall were still taken aback when the Newcastle Steel Works players arrived on stage – each carrying a wooden chair. They then proceeded to sit in the now ‘traditional’ formation before Albert Baile took to the stage.

Transfixed

The huge audience remained transfixed – as were the ‘overflow’ of those who couldn’t get in, and heard it relayed by Marconiphone to the nearby ballroom. Arthur Stender on principal cornet led the way, the ensemble playing bright and almost flawless in execution.

Although shocked by what Harry Mortimer later said was a “sensational” victory, the announcement was greeted with warm applause, the players immediately trying to get their pictures taken with the ‘new’ £2,000 Gold Trophy (top of page).

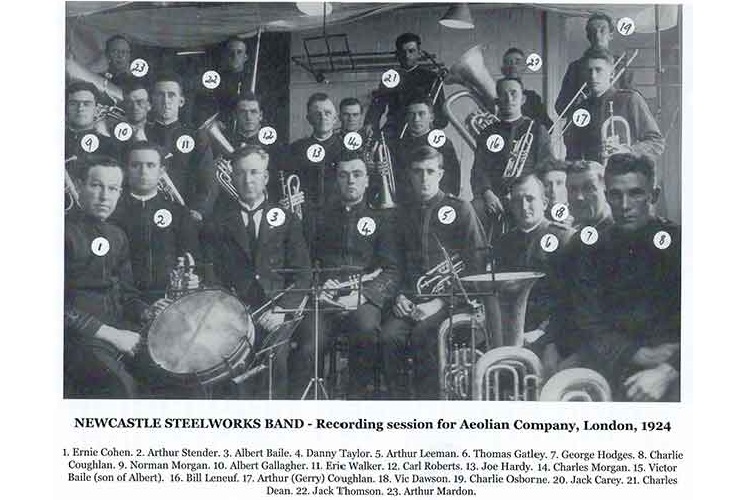

Buoyed by their success the band became an increasingly popular concert attraction, as well as being invited to undertake a recording session with the Aeolian Recording Company (below).

Underlying rancour

Some underlying rancour still existed though. The British Bandsman newspaper published an Australian article that said: “There is a desire in certain quarters in England as well as Australia, to discount A H Baile’s part in Newcastle Band’s big victories in England. The cry is that ‘so and so’ helped Baile put the polish on.

Is it wrong to ask the ‘helpers’ why they did not put a similar finish on their own bands?

The Newcastle Band’s victory shows up the weakness of English contesting methods, where one man may conduct any number of bands at one contest. It is strikingly evident that where a chain of bands place themselves under the charge of one man, that the result must be disastrous to the majority of the chain.

One man, many bands, is a method that makes for bad playing. Many conductors, mean numerous ideas – greater individuality, more originality, better bands.”

Crystal Palace

The band was subsequently invited to compete at the National Championships on 27th September at Crystal Palace.

Huge crowds once again attended the event, and although Besses o’ th’ Barn pulled out with yet another case of ‘Australitis' according to the anonymous British Bandsman northern correspondent, ‘Moderato’, Black Dyke had fully recovered. They were joined by the dominant St Hilda Colliery (winners in 1920 and 1921), Horwich (1922) and defending champion Luton Red Cross to reinstate British honour.

In addition, Arthur Stender performed his signature solo, ‘Zelda’ whilst Harry Mortimer was heard with Luton Red Cross playing his, ‘Shylock’.

And so it proved. Newcastle was placed third, behind St Hilda and Black Dyke – whilst as part of the evening Grand Festival Concert they performed ‘Life Divine’ under Baile’s direction.

In addition, Arthur Stender performed his signature solo, ‘Zelda’ whilst Harry Mortimer was heard with Luton Red Cross playing his, ‘Shylock’.

Packed to the chandeliers

Mortimer (above) later wrote that despite the press billing it, “as the champion of England and his counterpart from Australia”, it was “just overblown journalism”.

He added that in playing to a hall “packed to the chandeliers”, Stender, “…was brilliant. There was nothing of the element of competition between us. Arthur and I finished the evening as firm friends.” They were to meet again some 25 years later.

The famous Gold Shield did however return from ‘Terra Australis’ 12 months later – although in 1925 it wasn’t presented to the winning Creswell Colliery Band on the day of their British Open success. Due to a Customs oversight it was stuck in the hold of a ship moored on the Thames. They got their hands on it a week later.

No return

There was though to be no return for the newly crowned British Open champion to defend its title (although an ‘all-star' Australian Commonwealth Band with Stender in its ranks did perform in 1926).

The famous Gold Shield did however return from ‘Terra Australis’ 12 months later – although in 1925 it wasn’t presented to the winning Creswell Colliery Band on the day of their British Open success.

Due to a customs oversight it was stuck in the hold of a ship moored on the Thames. They got their hands on it a week later.

Pyrrhic victory

It was also to prove a pyrrhic victory for the Newcastle Steel Works Band. Much like modern day elite level champions, their success did not bring substantial cash reward.

When they finally returned to the port of Freemantle they were so short of money they sold their uniforms to the nearest brass band – Albert Baile’s former City of Perth.

The band itself was also exhausted by its adventure, and they only continued for a few more years, folding in 1932. The steel works after which it was named continued in production until 1995.

Now they are no more than a footnote in the history of the British Open Championship, although nothing will erase the magnitude of their success a century ago.

Tim Mutum