The first issue...

The decision to stop producing a weekly on-line version of British Bandsman magazine in June this year marked the end of the final chapter for a publication that for 135 years served the brass banding world with distinction.

The name will survive thanks to the efforts of Rob Tompkins, a brass band enthusiast who will maintain it as an on-line presence, but its format is no longer one that retains its position (according to the Guinness Book of Records) as the world’s oldest weekly musical periodical.

Battle

It was the somewhat predictable outcome to an ongoing battle fought against the progress of technology and of changing reading habits, investment needs, increasing production costs, lowering advertising revenues and above all else, time.

In a print age that has grown increasingly digital and ever more immediate, it simply did not have the ability to change quickly enough to adapt. In that it is has not been alone, and thankfully the title remains in circulation.

It was the somewhat predictable outcome to an ongoing battle fought against the progress of technology and of changing reading habits, investment needs, increasing production costs, lowering advertising revenues and above all else, time.

However, it is now (although hopefully it can find its niche to flourish) a reminder of a publishing past – that much like the printing of the updated two paged historical results sheet at the British Open for audience to take home with them after the contest, may never return.

But what a past.

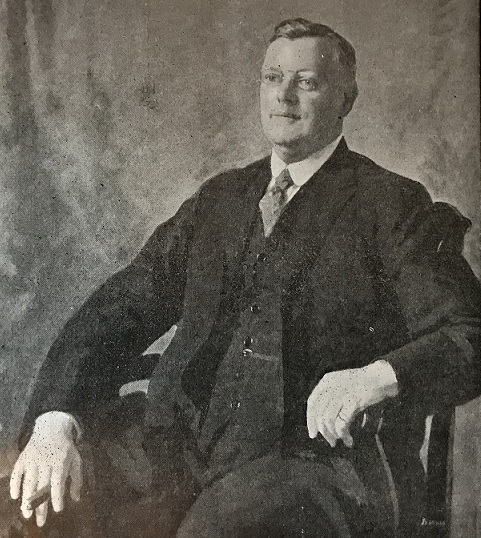

The first Editor: Samuel Cope

The Bandsman

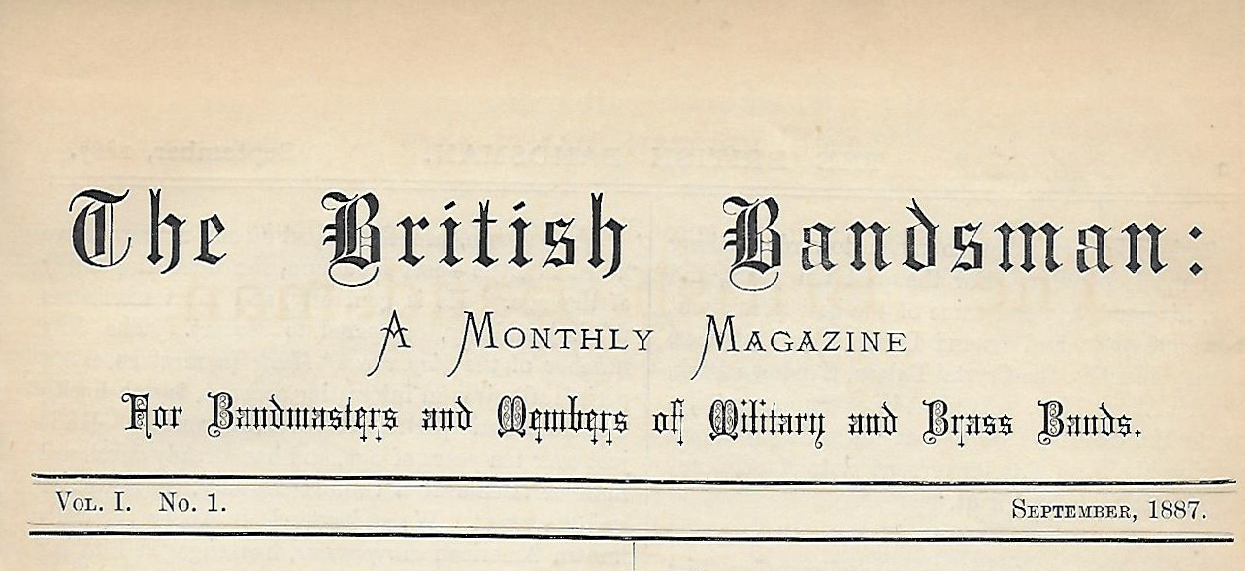

The publication was founded by Sam Cope in September 1887 as ‘The British Bandsman: A monthly magazine for Bandmasters and Members of Military and Brass Bands’; a rather ungainly title that readers soon shortened to ‘The Bandsman’ or ‘BB’.

Cope was an astute, quick-witted Cornishman who recognised an opportunity to make his mark on a thriving cultural phenomenon. The last decades of the Victorian era were arguably the last expansionist times for the banding movement – one that was still largely unregulated and randomly reported.

He had also experienced first-hand the pernicious attitudes that he felt could undermine the foundations of a banding movement still growing in exciting, but rather feral directions.

Marshall opinions

After discussion with friends, he conceived the idea of a magazine “to chronicle events and marshall opinions.”

It was the latter that set it apart from Brass Band News, first published since 1881, as he set about broaching wider topics such as issues on teaching, musical philosophy and progressive, regulated direction.

It was a template, tempered by Cope’s brave editorial advocacy (alongside joint editor James Waterson) that soon made it a success and defined the approach that future editors and owners had to meet.

It was a template, tempered by Cope’s brave editorial advocacy (alongside joint editor James Waterson) that soon made it a success and defined the approach that future editors and owners had to meet.

In one of its earliest issues in a review of the latest music for bands it both welcomed the euphonium solo ‘True till Death’ as being one “we are anxious to see more music published for this instrument”, whilst the ‘Messiah Sacred Quickstep’ was in the critic's view “perverted to suit the exigency. Some some things are too hallowed to brought into profane use - and this is one of them…”

Issues had solos published on a regular basis

British

The original title changed over time – from ‘The British Musician’ to ‘British Bandsman and Contest Field’, but in 1906, it became ‘The British Bandsman’. The definitive article disappeared in the 1970s, returned, but was dropped for good in 1987.

Cope observed there were many German bands busking in the streets of London, and so, decided to call his magazine “British” to avoid any identification, as he said, “with these foreign gentlemen.”

Oddly, the decision to claim the epithet ‘British’ has a resonance today – although it regularly reported on overseas news – including the death and sale of items from the estate of the composer Jacques Offenbach, who was described as an “ephemeral character” who was “the idol of the Parisians”.

Cope observed there were many German bands busking in the streets of London, and so, decided to call his magazine “British” to avoid any identification, as he said, “with these foreign gentlemen.”

Title

He also considered naming it ‘The British Army Bandsman’, but somewhat contradicted his aim of it successfully broadening its appeal to be bought by a civilian banding public.

As for giving it a non-gender specific title? This was 1887.

Cope was to enjoy three stints as Editor, including preceding and then succeeding Herbert Whiteley who enjoyed a 24-year tenure from 1906 – 1930, and a short period under James Browne (1895-1898).

The legendary John Henry Iles

Monthly to weekly

Cope’s tenure after the magazine had been acquired alongside R Smith and Co by the entrepreneur John Henry Iles was perhaps the most significant in its history.

Iles turned ‘The Bandsman’ from a monthly to a weekly publication in 1902, cleverly employing a robust sales pitch to subtitled it, ‘A newspaper devoted to brass bands’.

His monopolistic desires (he owned the National Championships and later took over the running of Belle Vue), eventually destroyed him, but his contribution to all three was immense.

Immense contribution

Publication costs swallowed up the cover price of 1 penny, but advertisers soon flocked to get their names and products in print to a growing readership. Despite occasional financial uncertainties, it soon turned a regular, healthy profit.

Flamboyant, egocentric, and occasionally rash, Iles later became Editor from 1942 - 1951.

His monopolistic desires (he owned the National Championships and later took over the running of Belle Vue), eventually destroyed him, but his contribution to all three was immense.

A very British publication...

Free to the troops

For instance, during the First World War, when issues were at times reduced to just eight anaemic pages of news, Iles subsidised the postage of hundreds of free copies to troops overseas.

The return of peace saw ‘The Bandsman’ as the undeniable ‘voice of the movement’, and although it was one that had been decimated by the slaughter of the conflict, it soon revived.

The return of peace saw ‘The Bandsman’ as the undeniable ‘voice of the movement’, and although it was one that had been decimated by the slaughter of the conflict, it soon revived.

Iles kept the cover price at tuppence, but it was decided to cease publishing largely unedited and unreliable contest reports, which Whiteley (with perhaps a prophetic eye to a century ahead) considered, “a relic of the past”.

Advertisers knew the value of success

Strife

The inter-war years were also marked by strife – although of an industrial kind.

In an echo of what was to be felt half a century later in the 1970s, paper costs increased enormously. The miners strikes and General Strike of 1926 impacted on the circulation figures and, as repeated in the mid-1970s, some issues were never published.

The magazine at times survived by the skin of its teeth.

Elgar wrote in the Golden Era

Golden era

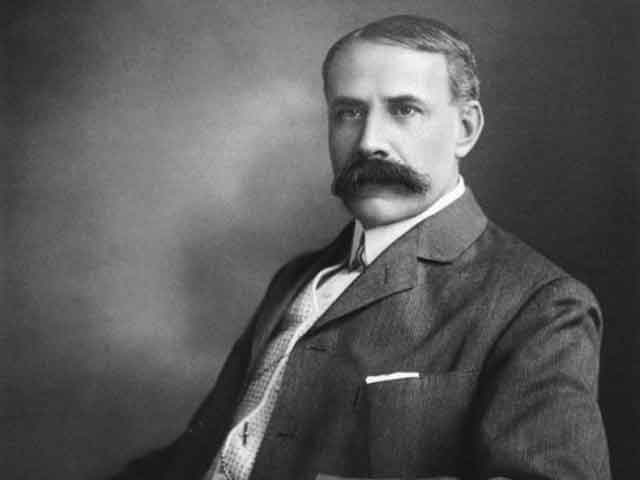

What would have been lost if it had gone under would have been incalculable – especially given our reflection on what was to be called ‘The Golden Era’ of brass band contest composition.

Up until the outbreak of the Second World War, a number of leading British composers wrote for the medium. Whiteley, through the columns of the paper, and his influence with Iles, deserves huge credit for that, as Whiteley’s daughter, Marjory Nicholas told Arthur Taylor for his book, ‘Labour and Love: An Oral History of the Brass Band Movement’.

“It was my father who chose all the test pieces by people like Cyril Jenkins, Henry Geehl, Hubert Bath, Dr Denis Wright and Sir Edward Elgar. He spent years begging and pleading with Elgar to write a piece for the bands.”

“It was my father who chose all the test pieces by people like Cyril Jenkins, Henry Geehl, Hubert Bath, Dr Denis Wright and Sir Edward Elgar. He spent years begging and pleading with Elgar to write a piece for the bands.”

Showman not a musician

She added, “I didn’t know John Henry Iles as well as these other people – the composers – but I got the impression that he wasn’t really all that interested in music. He was interested in what you might call the ballyhoo – he was a showman, not a musician.”

It is therefore a reasonable argument to make that without the British Bandsman and those behind it, the likes of Holst, Elgar, Ireland, Bantock, Howells and Bliss would never have written for the medium.

It is therefore a reasonable argument to make that without the British Bandsman and those behind it, the likes of Holst, Elgar, Ireland, Bantock, Howells and Bliss would never have written for the medium.

Whiteley’s retirement saw Cope return, but no longer possessed of the energy needed to devote his time to keeping the publication an essential part of the nation’s reading habits, he appointed Alfred Mackler as his assistant.

Mackler (who later left for war time service) was a journalist of integrity and insight, informed and clever. News features became more prominent, features were supplemented with photographs and the magazine was redesigned. He returned in 1963 as Editor.

The inter war period was the last great mass participation era

Bombed

Iles meanwhile was declared bankrupt in 1938, but despite his own financial woes the Bandsman carried on. Although ostensibly the Editor (taking over from Cope in 1942), it was his indefatigable secretary Frances Bantin, who carried the brunt of the work of ensuring the magazine was published, at times under the most appalling conditions.

Twice the offices at 210 Strand were nearly bombed out of existence as the Luftwaffe targeted the capital.

Twice the offices at 210 Strand were nearly bombed out of existence as the Luftwaffe targeted the capital.

Labour of love

Bantin took on the role with Iles in 1921 and it was therefore appropriate that she provided the front-page coverage of his death on 29th May 1951.

She wrote, “Everyone will agree that it has been his influence and work which have brought brass bands to their present position.

Since he took an interest in them in 1898 it has been a labour of love to him to do everything he could for their advancement.”

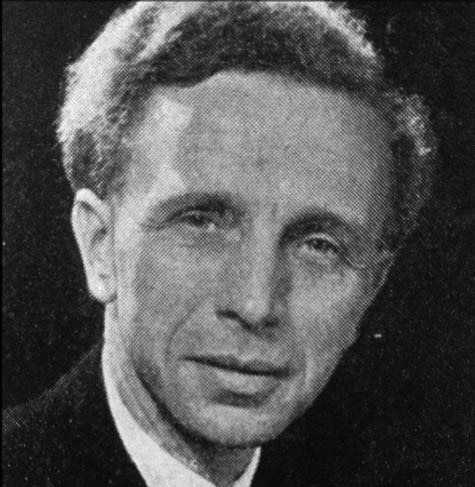

The new age with a new voice - Eric Ball

A new voice

Indeed he had, but in his later years (Bantin died in 1964 after giving the magazine 34 years of dedicated service) the magazine had lost its way – burdened in part by Iles’ own preoccupation for nostalgia and for a rather timid approach to reporting that remained in a time warp of deference.

Yet, as the new Elizabethan era blossomed the publication found a new zest under the editorship of Eric Ball (1951-1963 and 1964-1967).

With the likes of Edwin Vaughan Morris (wring under the name of David Neilson) able to provide an established network of news providers and with connections to the influential movers and shakers such as Harry Mortimer, now at the BBC, it found its voice again.

Tim Mutum