Part one: Finding a voice

When composer Philip Sparke decided to secrete themes from Wilfred Heaton’s ‘Contest Music’ in ‘Variations on an Enigma’ (1986) for brass band, little did he or anyone else know that Heaton may have hidden tunes of his own below the surface of his work.

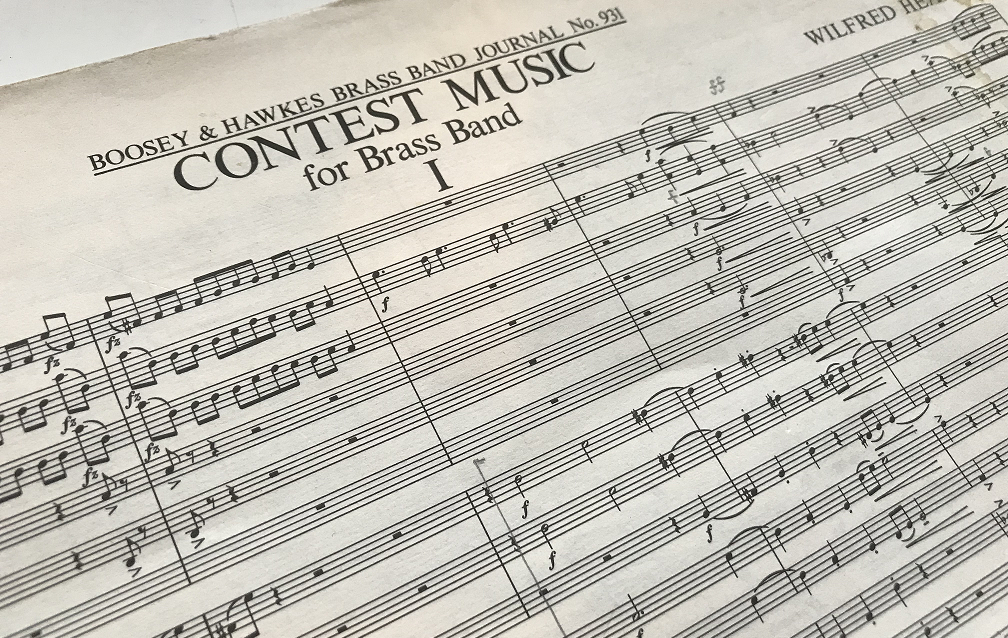

Since its publication for the 1982 National Finals it has become a classic of the band repertoire, widely admired for its consummate craftsmanship and expressive range.

Heaton would likely baulk at the idea of any emotional context for ‘Contest Music.’

Yet there is no denying the austere beauty of the slow movement and the humour of the finale, during which he introduces what sounds like ‘Old Uncle Tom Cobley and All’ on horn and euphonium following the big climax.

It never fails to raise a smile. There is nothing gratuitous in his music and he was certainly not one for cheap laughs.

So why is it there?

Heaton the conductor

Heaton was a private man and rarely disclosed anything about the inner workings of his music or the nature of his inspiration.

Prior to the 1988 Open Brass Band Championship, when ‘Contest Music’ was selected as the test piece, conductor and composer Bramwell Tovey travelled up to Harrogate to visit the composer.

Uncle Tom Cobley

When asked about the ‘Old Uncle Tom Cobley’ reference, Heaton declined to be drawn.

A few days later Tovey guided his Rigid Containers players to a memorable British Open victory. Heaton later confirmed to a friend from Harrogate Town Band that the reference was a signal that he had put his ‘all’ into the piece - ‘Old Uncle Tom Cobley and all’!

Every note has its place in a taut series of musical arguments. I am doubtful that he would have paraphrased such a familiar ditty without a sound musical rationale.

Having spent years delving into every detail of Wilfred Heaton’s music and researching as much about his life as his reticence made possible, I was convinced that the quotation held a key to unlocking hidden depths.

‘Contest Music’ is one of Heaton’s most considered scores.

Every note

Every note has its place in a taut series of musical arguments. I am doubtful that he would have paraphrased such a familiar ditty without a sound musical rationale.

I believe it is far from a random gesture, as I hope to demonstrate.

Bramwell Tovey made enquiries before leading Rigid Containers to a British Open victory

Basis

Back in March 2000, in what turned out to be our final telephone conversation before he died a few weeks later, Wilfred let slip that ‘Contest Music’ was based on three compositions sketched in the early 1950s, over 20 years before Geoffrey Brand’s invitation to provide a test piece for the 1973 National Brass Band Championship finals.

Wilfred told me that they weren’t written as a single entity but as exercises in various techniques of thematic metamorphosis. He’d been encouraged in this direction by one of the most in-demand teachers of the era, Hungarian émigré Mátyás Seiber (1905-1960).

Wilfred let slip that ‘Contest Music’ was based on three compositions sketched in the early 1950s, over 20 years before Geoffrey Brand’s invitation to provide a test piece for the 1973 National Brass Band Championship finals.

In the immediate post-war years, after returning from wartime service in the RAF, Heaton was determined to expand his horizons and fulfil a childhood ambition of a life as a professional composer and conductor away from the band world.

Comfortable voice

In his teens, his precocious gifts had resulted in some of his best loved pieces, including the meditation ‘Just as I Am’, and first versions of ‘Praise’ and ‘Toccata’. Now, he recognised that he would need to harness his instincts with a stronger, more reliable technique and develop, as he described, ‘a voice in which I could feel comfortable’.

Typically, he aimed high and travelled down to London from his Sheffield brass instrument repair shop for sessions with Seiber.

How many lessons he paid for is not clear. Seiber was expensive and money was tight. His apprentice Herbert Cocking thinks that he couldn’t have afforded more than a handful.

Mátyás Seiber (credit: family archive Julia Seiber Boyd)

Heaton later acknowledged the value of Seiber’s ‘insistence on Bach studies above all’. He took all his pupils, however gifted, back to basics with a rigorous study of J.S. Bach’s two and three parts inventions, establishing the value of every note, every twist and turn of counterpoint.

Ideal

Bach became Heaton’s ideal of musical perfection. Before letting his pupils loose one their own work, Seiber followed up with a deep and meaningful exploration of Haydn’s classical forms and the contemporary ‘equivalents’ of his fellow countryman Bela Bartok, the pedagogical keyboard studies ‘Mikrokosmos’ in particular.

How transformative this experience was for Heaton can be heard in every bar of ‘Contest Music’.

Seiber was intent on offering a reliable technical grounding to whatever style his students chose to work rather than imposing a doctrinaire method. He encouraged all his pupils to begin with a fundamental theme.

Every bar

This could be any collection of organised pitches, from a simple tune to a 12 tone row, as long as the composer maintained an ‘obligation to the motif’, sifting for the nuggets from which to develop a musical argument.

How transformative this experience was for Heaton can be heard in every bar of ‘Contest Music’.

But that was 20 years away. How can we account for the chasm between initial inspiration and final outcome?

Wifred Heaton

The 1950s was a decade of personal transformation for Heaton - a ‘drastic re-orientation’, he called it, embracing a complete change in his personal circumstances, spiritual outlook and professional life.

By taking on an apprentice, he was able to spend more time away from his brass instrument repair shop, earning much needed extra income playing French horn, teaching and conducting.

The 1950s was a decade of personal transformation for Heaton - a ‘drastic re-orientation’, he called it, embracing a complete change in his personal circumstances, spiritual outlook and professional life.

In 1963 he closed the business, moving with his family to Harrogate for a fresh start as a freelance horn player, busy orchestral conductor and fully qualified instrumental teacher.

Open doors

Seiber also did what he could to open doors to the wider music profession in the south, recommending that Heaton submit some work to Society for the Promotion of New Music, which Seiber had established with Rumanian émigré Francis Chagrin (1905 - 1972) after the war.

Heaton submitted two compositions, ‘Rhapsody for Oboe and Strings’ (Op. 1) and ‘Three Pieces for Piano’ (Op.2).

They were accepted and received London premieres in 1954. With their post-concert discussion and in forensic critiques, it’s my guess that the reserved Heaton found these workshop sessions less than congenial and continued to work in the isolation of his music room without any further tuition or advice.

Trapped

However, composition proved an intractable problem. Heaton discovered through his exposure to the London scene, that he didn’t much like the cut and thrust, the networking and self-promotion that went along with being a professional composer.

‘I felt temperamentally unsuited to it’, he observed on one occasion.

So, he found himself trapped.

However, composition proved an intractable problem. Heaton discovered through his exposure to the London scene, that he didn’t much like the cut and thrust, the networking and self-promotion that went along with being a professional composer.

What he wanted to write was too ‘advanced’ for The Salvation Army of the day, but in his mind at least, he considered the voice he had found was too old fashioned compared with the avantgarde sounds emanating from music colleges in London and Manchester.

The National Championship had to wait until 1982 to premiere the work

Three decades

Heaton had decided in his teens that he would give up composing altogether if he could not break free from the band world.

By his mid-30s, he had all but stopped. He didn’t write anything brand new until he retired almost three decades later. All the major works that emerged in the intervening years, not just ‘Contest Music’, were reworkings of music composed or sketched half a lifetime earlier.

Brass bands didn’t really catch up with Heaton’s musical adventures until the late 1960s, when Toccata was eventually performed by the International Staff Band at a Royal Albert Hall festival for SA songster (choir) leaders.

Brass bands didn’t really catch up with Heaton’s musical adventures until the late 1960s, when Toccata was eventually performed by the International Staff Band at a Royal Albert Hall festival for SA songster (choir) leaders.

Geoffrey Brand was impressed when he heard it and, sharing SA musical roots, he approached Heaton about writing a National finals test piece when he took over the National Championships in 1972.

Four months

It took Heaton just four months to put ‘Contest Music’ together - from December 1972 to March 1973. Brand was surprised how quickly it was completed.

Of course, he was unaware that Heaton had exhumed material from his ‘unregarded corner’ as the basis for this his only commissioned work.

What happened to the piece thereafter, its rejection, occasional concert performance, publication and eventual National contest performance in 1982, has entered into the annals of brass band legend.

What secrets may lie beneath the brilliant surface of the music, I’ll endeavour to reveal when I go hunting for tunes.

Paul Hindmarsh