Historians have long debated the dates of the chronological time frame of the first, and perhaps only, ‘Golden Age’ of the brass banding movement in the UK.

A remarkable social phenomenon certainly occurred in the late Victorian era that combined mass production and retail innovation with a communal sense of moral rectitude that brought music making to working class communities from South Wales to the north east of England, the villages of Kent to the Clyde shipbuilding yards of Glasgow.

Caesars

That era ended in the trenches of the Western Front, whilst the lineage of great conductors such as Gladney, Owen, Swift and Rimmer, who moulded its competitive destiny like omnipotent Claudian Caesars was by then already consigned to the history books.

The years between the World Wars perhaps saw the last great displays of a mass participation movement; boosted by a short series of works by noted composers, the emergence of radio as a means of national musical entertainment and the final generation of personalised brass band industrial philanthropists.

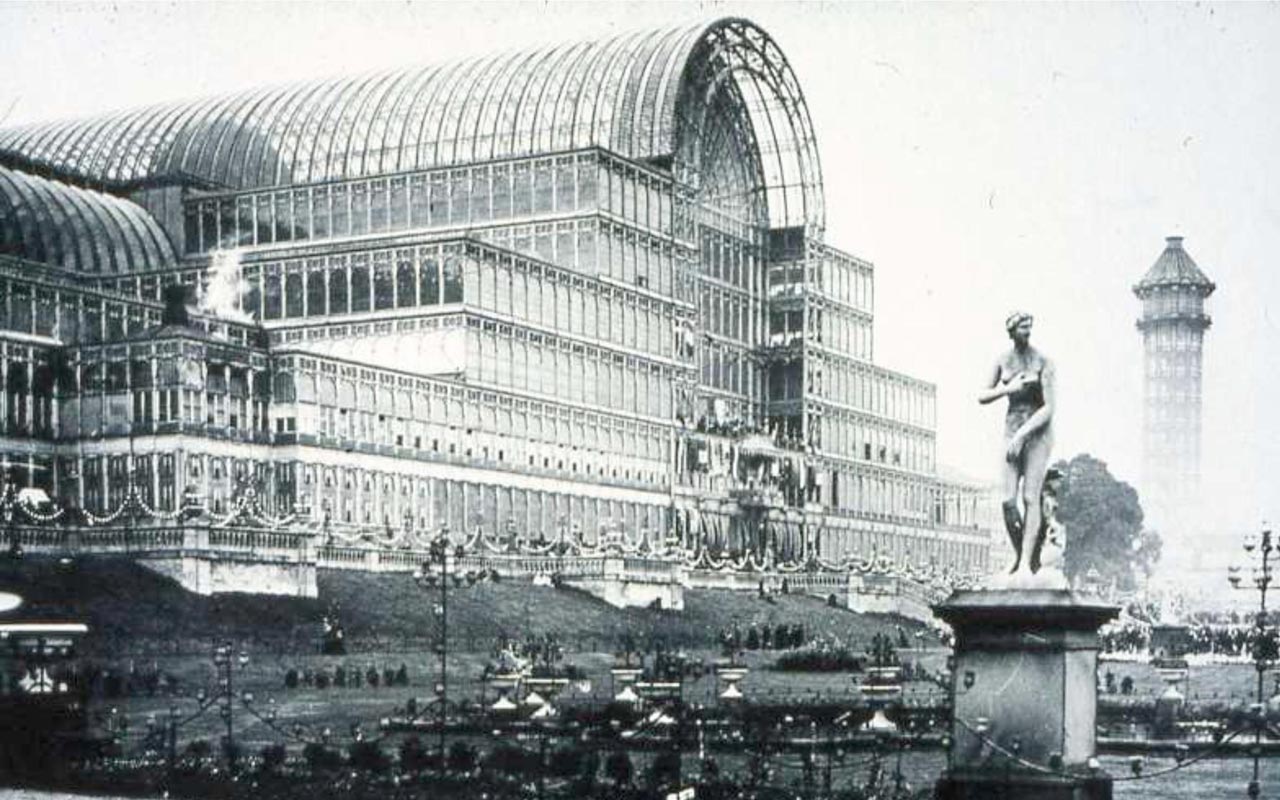

That era ended in the flames that engulfed The Crystal Palace in November 1936 - a metaphoric Götterdämmerung; a destructive conflagration of glass and iron seen glowing in the skies of London that was to be repeated in more sinister fashion in the years to come.

That era ended in the flames that engulfed The Crystal Palace in November 1936 - a metaphoric Götterdämmerung; a destructive conflagration of glass and iron seen glowing in the skies of London that was to be repeated in more sinister fashion in the years to come.

Crystal Palace: Before Götterdämmerung

The immediate post war period was one of retrenchment and reorganisation. Thereafter the 1950s were locust years of inactivity and planning, the 1960s an illusion to former glories, the 1970s offering only occassional spasms of hope.

Each decade marked a further diminishing in participation and influence. A once rich seam of musical gold, mined and crafted througout the UK had long since been exhausted.

Then came the 1980s.

Huge change

In the UK it was decade of huge social and economic change – brutal at times in imposition and effect. Working class communities in particular paid a heavy Thatcherite price; the industries that provided the very basis of their existence cut, closed and demolished before their eyes.

Changes in education policy and welfare dependency also unraveled the hitherto close-knit weave of the social fabric of communities that had proudly supported their own provision of artistic endevaour – Welfare Halls and Institutes, community centres, libraries and sporting clubs.

Changes in education policy and welfare dependency also unraveled the hitherto close-knit weave of the social fabric of communities that had proudly supported their own provision of artistic endevaour – Welfare Halls and Institutes, community centres, libraries and sporting clubs.

Jolted into life

Nothing was the same again in a “get on your bike“, “loads of money“ culture that seeped insidiously into homes through red top newspapers and breakfast television screens.

Despite this hinterland the brass band movement was somehow jolted into life – like a critically ill hospital patient given an emergency form of musical CPR.

The 1984/85 Miners' Strike was both brutal in imposition and effect

Although it did not signal a resurrection to the gilded splendour of Edwardian certainty, a rejuvenation was certainly made.

New names

Notably it marked the emergence of compositional talent that provided the foundation on which major contest repertoire was built for the next 30 years.

New names started to make their name on the rostrum, an exciting generation of performers emerged from the halls of brass band learning at Salford University and the RNCM in Manchester.

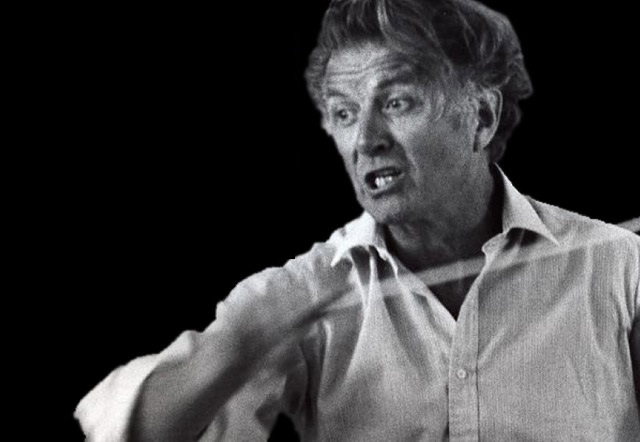

Although unable to attract the likes of a 1980s Holst or Elgar, the steady flow of inventive works from Edward Gregson, Philip Sparke, Philip Wilby, John McCabe and Derek Bourgeois was supplemented by occasional interventions by the likes of George Lloyd, Joseph Horovitz, Arthur Butterworth, Ray Steadman-Allen and Elgar Howarth.

The man who provided the musical apex: John McCabe

On top of this came enticing first and second-hand reflections by Michael Tippett, Richard Rodney Bennett, Peter Maxwell Davies and William Walton amongst others.

In 1982 there was long overdue acknowledgment of Wilfred Heaton when ‘Contest Music’ was finally used at the National Finals.

Contest change

The main contests also changed: The British Open finally moved away from its decrepit spiritual home at Belle Vue to the elegant refinement of the Free Trade Hall in Manchester.

The National Championships trimmed its cloth after demand for the Gala Concerts dwindled at a time when the cost of hosting the European, Lower Section and Youth Finals on the same weekend in the heart of Kensington soared (inflation was running at around 18% in 1980, ending the decade at 7.8%).

In tandem with what seemed to be the emerging power of the then European Economic Community (EEC) – it wasn’t until 1984 that Mrs Thatcher demanded “we want our money back” - the European Championships also headed across La Manche - never to return to Kensington Gore.

Acceleration mode

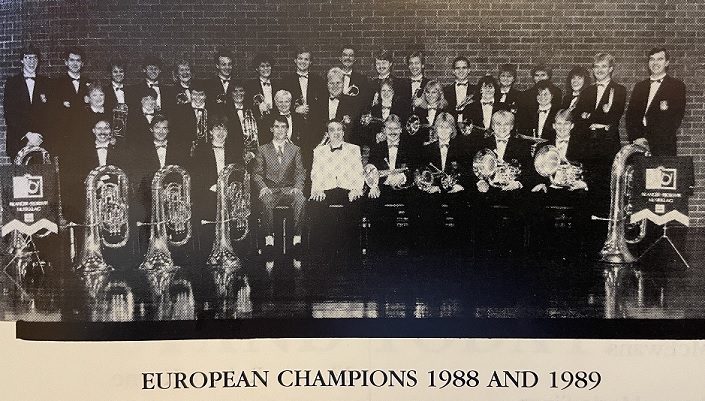

The 1980s saw European banding in acceleration mode. From Manger’s runner-up finish in 1982 to Eikanger’s first success in 1988, British pre-eminence started to show the first signs of long-term fissures to its ascendency. Further afield, numbers were dropping in the Empire outposts of Australia and New Zealand.

In contrast, the Swiss and Norwegian banding movements prospered with investment in organic musical soil, the Belgians and Dutch in more singular greenhouses of excellence.

European charge

In contrast, the Swiss and Norwegian banding movements prospered with investment in organic musical soil, the Belgians and Dutch in more singular greenhouses of excellence.

The changes brought consternation – especially from traditionalists, but in truth the writing had been on the wall for some time.

The British Solo Championships went into hibernation, television grew tired of Granada Band of the Year and BBC ‘Best of Brass’ (oddly at a time when the music provided by the likes of Howard Snell and others reached a golden zenith of its own), and the CISWO Miners Contest understandably became a shadow of its former self.

Howard Snell arrived but the Granada contest disappeared

Yet, the Pontins Championships remained hugely popular, Brass in Concert, Yeovil and other regional events such as the Joshua Tetley Open filled the contesting calendar.

Radio broadcasting still included regular slots with ‘Listen to the Band’, ‘Among Your Souvenirs’, Friday Night is Music Night’ and ‘Bandstand’. By the end of the decade local radio stations had begun to regularly feature their own brass band programmes.

Darwinian ethos

Despite the obvious challenges brought by a political wind of change that blew through brass banding heartlands with a Darwinian ethos, it still seemed like a new ‘Golden Age’ had miraculously appeared - touched by an unknown Croesus-like hand of fortune.

Even the number of bands that participated at the Area Championships took a turn for the better. In 1983, 520 performed, rising to over 590 in 1989. From then on decline - numbers dropping to 522 by 1997, spiralling towards 500 by the end of the century.

Despite the obvious challenges brought by a political wind of change that blew through brass banding heartlands with a Darwinian ethos, it still seemed like a new ‘Golden Age’ had miraculously appeared - touched by an unknown Croesus-like hand of fortune.

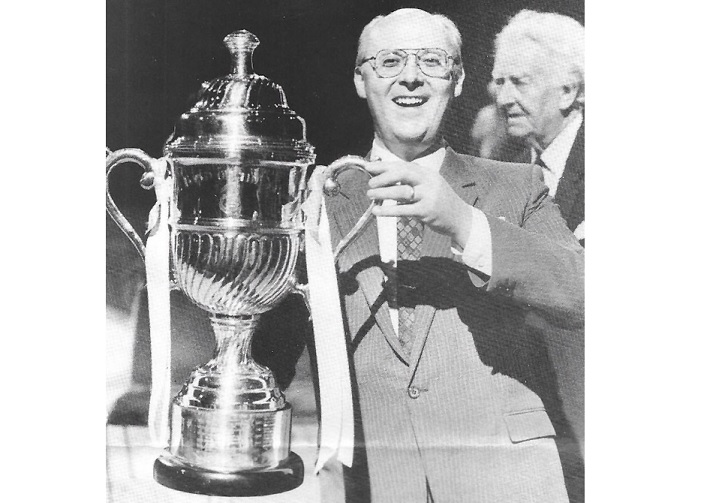

Peter Parkes: The commanding conducting figure of the 1980s

Apex

The musical apex, the most beautifully crafted piece of Faberge-like musicianship came at its mid-point: Black Dyke’s series of contest performances in 1985 under Major Peter Parkes (their own era ended in 1989).

It culminated in a truly memorable rendition of ‘Cloudcatcher Fells’ at the National Championships, which remains, like pure gold, untarnished by time.

The band (with Grimethorpe) appeared at the Proms in 1981 and again on their own in 1987 (although it was to be another 20 years before they returned).

It culminated in a truly memorable rendition of ‘Cloudcatcher Fells’ at the National Championships, which remains, like pure gold, untarnished by time.

However, despite their contest successes Black Dyke was still challenged by a host of other high class major title winning bands of the era – from Cory to Desford at London, Fairey, Imps and Grimethorpe at the Open.

Big beasts

The Championship Section was a hunting ground full of big beasts – and there were plenty of them from just about all corners of the UK: There was Whitburn in Scotland to City of Coventry, GUS and Jones & Crossland in a ‘hot-bed’ Midlands, the re-emerging Besses and Foden’s, Leyland and a vibrant Kennedy Swinton in the North West, Brighouse and Brodsworth in Yorkshire to Sun Life in the West, Newham in London to Ever Ready in the North.

European power: Eikanger Bjorsvik

No appetite for change

It couldn’t last - the banding movement itself (much like today) had no appetite for much needed, long overdue structural change. Self-preservation rather than musical self-advancement soon became an underlying ambition.

The advent of the First Section in 1992, meant to provide a stepping-stone to top-flight excellence, only led to the Championship Section becoming a bloated landscape of mediocrity.

Not then a Golden Age, but a period of golden moments nonetheless – even if historians may well hallmark it in the years to come as being 12 rather than 24 carat purity.

The obituary columns soon started to fill with once proud names – whilst others such as Foden’s, GUS, Leyland, Fairey, Stanshawe, Wingates, Yorkshire Imps and even Black Dyke Mills took on new identities to keep sponsors rather than patrician owners happy.

Others came and prospered, but far too many shone brightly only for a moment or two like an imitation Ratner’s ring (a man very much a product of the 1980s) before disappearing for good.

In retrospect the 1980s remain a remarkable period of resurgence against what was to become long term financial under investment in the arts, education and creative industries in communities that traditionally had so much to offer in terms of raw talent and material.

Not then a Golden Age, but a period of golden moments nonetheless – even if historians may well hallmark it in the years to come as being 12 rather than 24 carat purity.

Iwan Fox