Even the type face was ahead of its time...

50 years ago this month mankind was basking in the celebratory afterglow of Apollo 11’s return to earth following the first Moon landing.

Meanwhile, in rehearsal rooms across the UK, 21 conductors prepared to take one small step into the unknown themselves: ‘Spectrum’ had arrived.

Touchdown for them would be on September 6th 1969 at the King’s Hall, Belle Vue, Manchester.

In one giant leap of his own making Gilbert Vinter had freed bands from the musical tethers binding them to the earthly soil of contesting history. His composition might as well have landed on their stands from outer space.

Looking back half a century later you are left with the same feeling of admiration and bewilderment about his achievement as that in finding out that Apollo 11’s epic trip was backed by the computer power of a modern mobile phone.

However, what the end result of it all was, much like those pioneering lunar missions is now open to debate.

One thing is for certain though - nothing was ever the same again.

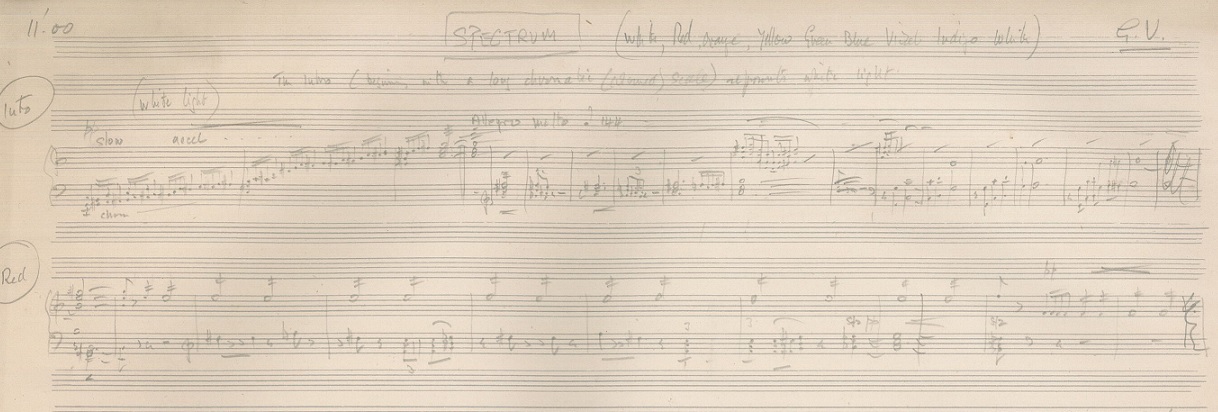

Pencil, paper and piano

Vinter drew up the plans to launch the test-piece into the firmament on a blueprint created by a pencil, paper and piano keyboard template that would have been familiar to Percy Fletcher or even Charles Godfrey before him. In 1969 Sibelius was still a name associated with a Finnish composer, not a music notation software programme.

The announcement of ‘Spectrum’ as 1969 British Open set-work was made by Jack Fearnley, the Director & General Manager of Belle Vue, from the stage of that year’s May Spring Festival in Belle Vue.

It was something of a coup.

The man who took the first step... Gilbert Vinter

The piece was earmarked for the 1968 National Championships, but Vinter was deeply upset that the organiser Vaughan Morris had accused him of being unprofessional in making available ‘John O’Gaunt’ for the 1968 British Open.

Hurt by the unfounded accusation (“You’re my composer” he allegedly told him) he withdrew the work and subsequently offered it to Harry Mortimer.

The piece was earmarked for the 1968 National Championships, but Vinter was deeply upset that the organiser Vaughan Morris had accused him of being unprofessional in making available ‘John O’Gaunt’ for the 1968 British Open.

Although there was no written announcement in the 1969 Spring Festival programme, the news would surely have tweaked the interest of three of the adjudicators there on the day; George Thompson, Alex and Rex Mortimer.

The conductors of Grimethorpe, CWS Manchester and Foden’s were to enjoy very different experiences on ‘Spectrum’ though.

A week later ‘The British Bandsman’ reported that the news would be met with “general approval and enthusiasm”. The British Open had, “inspired another major work from a composer of outstanding gifts”, which “will immediately conjure up music which is colourful and sensitive to changes of mood.”

They weren’t wrong.

Boycott

However, rumours started to surface that in some bandrooms it was also a mood of dismay and that a number of well known conductors were downright hostile to the work. It was claimed that the music was “too difficult” and that there was the possibility of some boycotting the event.

In retrospect, few would have seen anything like it: At the Grand Shield, Thoresby Colliery qualified for the British Open by playing ‘Peddar’s Way’ by Kenneth Wright.

Recalling the events with others some years later in Arthur Taylor’s book ‘Labour & Love’, Les Beevers of Brighouse & Rastrick said that ‘Spectrum’ “...didn’t half cause convulsions in some quarters”.

However, despite the grumblings (especially about the use of percussion), the British Open organisers held firm. The front man may have been H.F.B ‘Eric’ Iles, but it was Harry Mortimer who held the musical reins: And he was not for showing any sign of weakness.

However, despite the grumblings (especially about the use of percussion), the British Open organisers held firm. The front man may have been H.F.B ‘Eric’ Iles, but it was Harry Mortimer who held the musical reins: And he was not for showing any sign of weakness.

Not surprisingly, any insurrection died with a whimper, although it later transpired that Vinter was deeply upset that the work had caused such a response.

Of the 1968 participants, four dropped out. In came Brighouse & Rastrick, Cory, Carlton Main, City of Coventry, GUS (Footwear) and Thoresby. It was to be the strongest British Open field for many years.

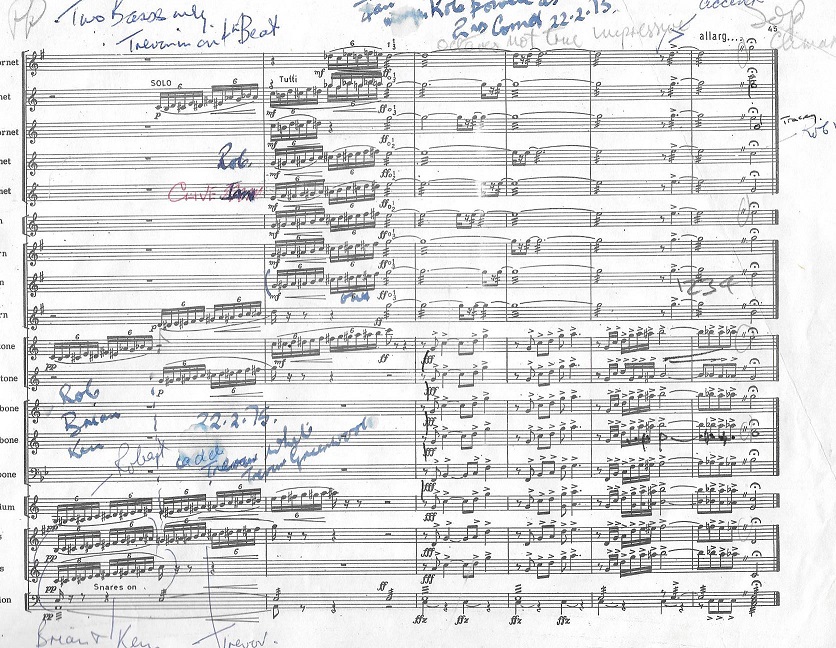

The score held challenges to be marked for conductors right up to the last chord

Enthused

At Grimethorpe meanwhile, George Thompson was enthused.

“’Spectrum’ had a tremendous impact on me,” he later recalled. “It did present problems, but it had a melody and a meaning behind it all – in spite of the little rhythmic difficulties. There was a pattern to the music - a message.”

It also struck a chord elsewhere. A young Ray Farr was shown the score by the composer before the event when he played under him at the BBC Midland Light Orchestra. “I remember we used to talk to Gilbert about his brass band compositions and he showed me ‘Spectrum’,” he said.

“He asked me what I thought, and I said, ‘Bongoes? Claves? You’ll never get brass bands to play with those instruments. When I heard it, I thought it was terrific - a wonderful piece.”

New ideas

There is little doubt of that today, but in 1969 the conductors were faced by 11 minutes of craftsmanship brimming with new ideas and textured colours.

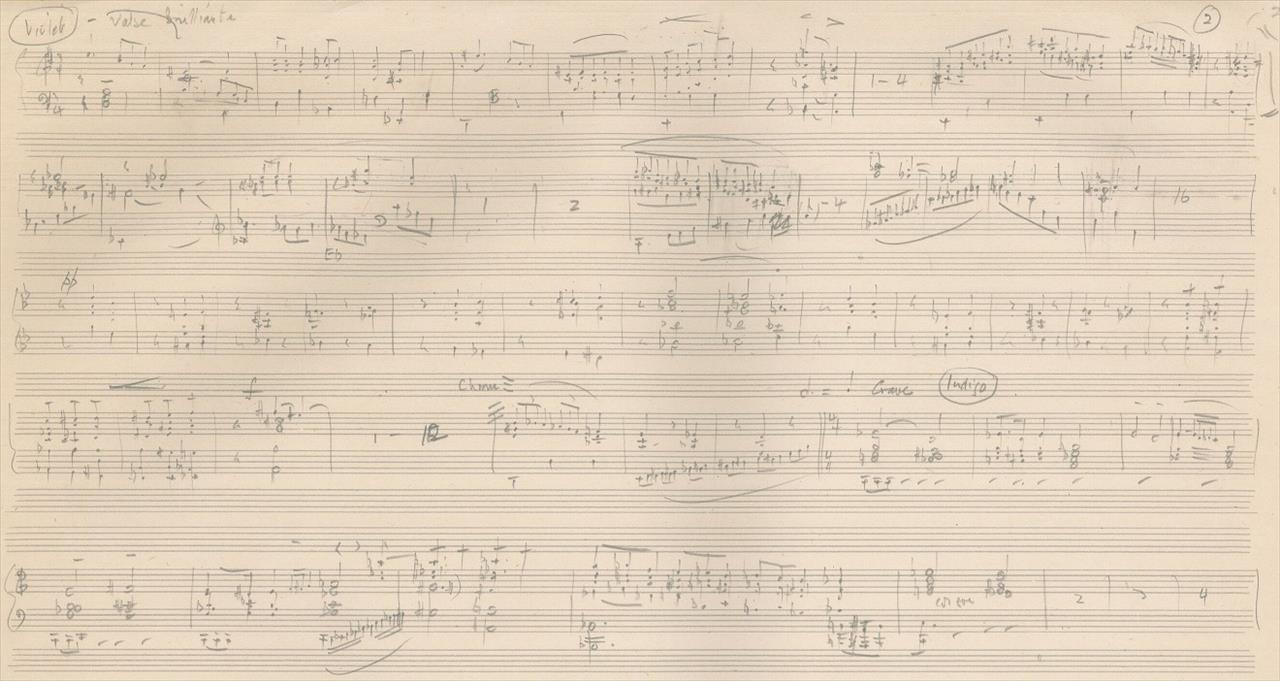

Today we known that they are Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Indigo and Purple, yet in his original 1968 short score sketches, Vinter opens and closes with the work with the colour White. The waltz was to be Violet and the final section, Indigo.

The short score is also annotated in his hand: “The Intro (beginning with a long chromatic (upward) scale - it presents white light.”

The opening was to build into a boiling point of colour

Vinter wanted it to represent the slow spiral effect of a kaleidoscope colour wheel - the ‘white light’ refracting emerging colours into the mind’s eye with increasing brilliance; a slow acceleration from standing start to pulsating boiling point - from a murky bubble of incoherence to a visceral primary splash of red.

Vinter wanted it to represent the slow spiral effect of a kaleidoscope colour wheel - the ‘white light’ refracting emerging colours into the mind’s eye with increasing brilliance; a slow acceleration from standing start to pulsating boiling point - from a murky bubble of incoherence to a visceral primary splash of red.

It was to be followed by a form of musical synaesthesia – variant wavelengths of the continuous spectral rainbow – red segueing into a languidly rhythmic ‘Orange’, a bright, brittle ‘Yellow’, a pastoral, flowing ‘Green’ and a playful, chilly ‘Blue’, the darkly playful 'Violet' waltz and dramatic, disturbing, 'Indigo'.

Vinter's original thoughts on the opening of Spectrum are shown on the score

Change of mind

So why then, the subsequent change of mind?

Much is made of Vinter’s final choice of ‘Purple’. By May 1969 he was terminally ill.

The same month, ‘The British Bandsman’ reported that he was on the 'sick list'; “...we echo the sentiments of bandsmen and musicians everywhere in sending our greetings and sincere wishes for a complete and speedy recovery.”

It was not to be.

Vinter's short score shows his original choice of colours for the final two movements

Perhaps conscious of his condition, but not wishing to directly signal the fact, he chose to use the Victorian colour associated with partial or ‘half’ mourning. It was a subtle but clearly personal intention.

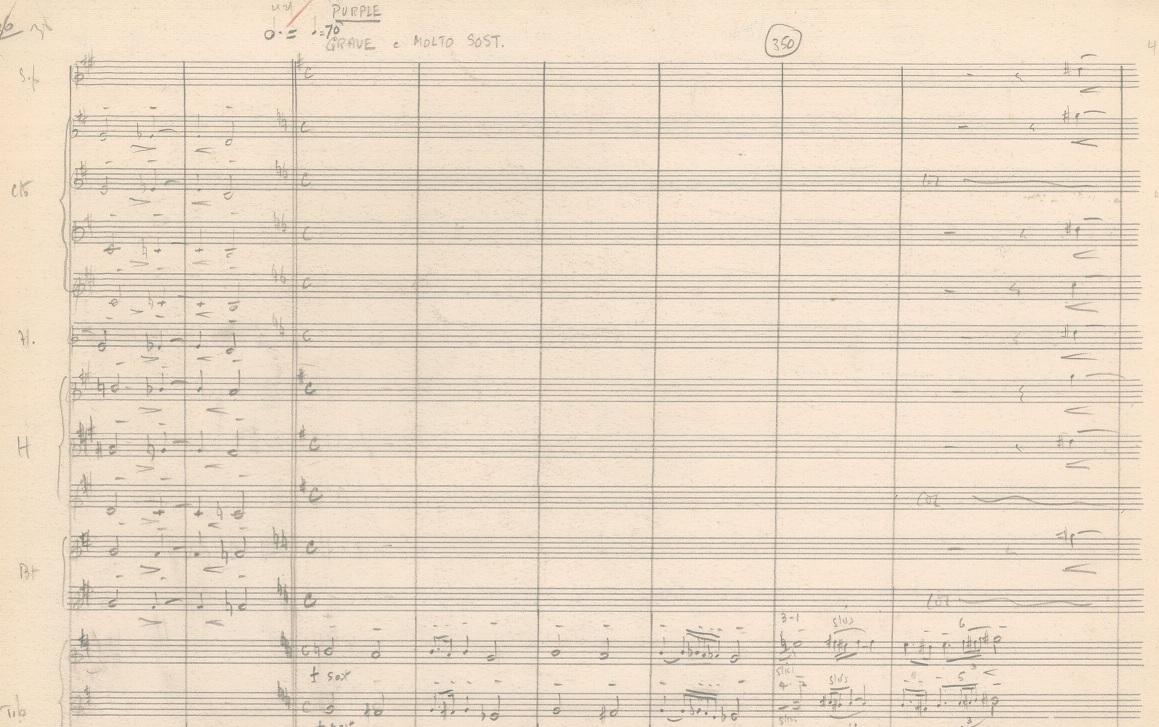

The subsequent handwritten score sent to the publisher in mid 1969 bears no crossing out or eraser marks: The final section, marked Grave, was now 'Purple'.

In that respect, the ornate 'Indigo' waltz that precedes it has a much darker edge of meaning; a heady last flourish before the haunting portent of impending death (there was only ‘James Cook’ and some trumpet interludes to follow).

In that respect, the ornate Indigo waltz that precedes it has a much darker edge of meaning; a heady last flourish before the haunting portent of impending death (there was only ‘James Cook’ and some trumpet interludes to follow).

Breakthrough

Elsewhere minds were focussed on other matters.

Just a month before the contest, ‘The British Bandsman’ (whose editor was Geoffrey Brand, conductor of Black Dyke), highlighted the ‘momentous’ decision to include percussion - one that was in their view, “a breakthrough in thinking”.

“If the brass band is to take its rightful place alongside the other responsive music making bodies in this country then it will be necessary for some revised thinking to take place and the willingness for change, as dictated by present trends to be admitted.”

The full score was sent by Vinter to the publishers with Purple as the final movement

Scene set

The scene was therefore set for history to be made.

Percussion players were signed (two were allowed), a stage plan implemented and the bands were able to use their own instruments.

The King’s Hall stage was lowered and extended for the contest to accommodate the larger sized bands (although the requirements - bongoes, claves, triangle, cymbal, side drum, bass drum, tambourine and wood block wouldn’t have filled a car boot nowadays).

In an odd quirk of appropriate fate, the carpet that covered the stage was a newly laid swirl of 1960s technicolor spirals and patterns.

The end of one era... the start of a new age

In the event, the contest day passed without any great incident, although it was announced that Gilbert Vinter would not be adjudicating as stated in the programme (Eric Ball acted as referee with the judges being Sir Vivian Dunn and John Carr). His poor health even prevented him attending.

In an odd quirk of appropriate fate, the carpet that covered the stage was a newly laid swirl of 1960s technicolor spirals and patterns.

Critics

Roy Newsome later recalled that the early responses to the work were muted, although there were the usual murmurs heard through the fog of cigarette smoke as a number of early draw fancied bands struggled (Black Dyke included).

In the end, the podium finishers played 16, 17 and 18 out of the 21 contenders, whilst the draw itself must have elicited a wry smile on the face of Harry Mortimer. His brothers had been drawn first and second with CWS (Manchester) and Foden’s. The two were rumoured to be amongst the biggest critics of the piece.

In the end CWS Manchester’s world premiere claimed fourth, Foden’s were nowhere. It says something that Ransome & Marles who eventually came fifth gave a performance described by Sir Vivian as; “From a good beginning there was a disappointment subsequently.”

What he made of those lower down the results table would have been interesting to note for posterity.

Excellent in every respect

World Champion Brighouse & Rastrick and defending champion Black Dyke (with Roy Newsome playing percussion) failed to make a mark (Dyke came 8th - “to no one’s surprise”, he later wrote), with GUS Footwear sneaking into sixth under Stanley Boddington.

Others simply found it all too much as John Carr alluded to in his remarks for second placed Carlton Main Frickley (drawn 17). “It is clear that the later bands in numerical order of playing are in a higher class than the remainder”.

“Complete conviction. Excellent in every respect”, wrote Sir Vivian. “It is going to be difficult to differentiate or to beat this”.

Fairey (18) also captured the “colour and flow” of the music to come third, but it was Grimethorpe that delivered the knock-out blow under George Thompson off the number 16 draw.

“Complete conviction. Excellent in every respect”, wrote Sir Vivian. “It is going to be difficult to differentiate or to beat this”. And so it proved.

It gave them their second British Open victory in three years. They also won again on it under Thompson on his penultimate contest appearance with the band in 1976.

The 1969 Champions: Grimethorpe Colliery Band

Historic day

In summing up the occasion, ‘The British Bandsman’ wrote; “The day had been eagerly anticipated by so many, for it was a historic day; percussion had come to Belle Vue, indeed to brass band contesting. There is no doubt the significance is considerable.

It is certain a changed attitude to the importance of percussion instruments will enter into the thinking of those who write and range music for brass bands. We are living in a time of change and bands are not immune from these changes or should they be.”

Vinter though was not there to witness his historic achievement. He had a month left to live.

Edward Gregson, a composer who many felt inherited Vinter’s mantle, added: “He was the man who changed all our thinking.”

Some years later Geoffrey Brand recalled that he felt that his “greatest contribution” was in his scoring for bands; “He produced different sounds from the same instruments. He used a vivid palette, especially in his introduction of percussion”.

Edward Gregson, a composer who many felt inherited Vinter’s mantle, added: “He was the man who changed all our thinking.”

And as for George Thompson, the man who led Grimethorpe to success on that historic day, he perhaps summed it up the best. “Of the two people I’ve had any personal dealing with I’d say Vinter and George Willcocks were the greatest loss to the band movement.

Just think what they might have been doing for bands if they were still alive.”

Statement of truth

In the case of Vinter that was as profound a statement of truth as any.

In his tribute following his death on the 10th October, aged 60, Harry Mortimer called him a composer “...of such forward thinking merit that not only we in the brass band world, but music generally, will be much the poorer for his passing.”

The loss to his family was even greater.

Dr. Andrew Vinter, the composer's son, said that 'Spectrum' "...devastated me and left me speechless. He (Gilbert) was surprised by my reaction because that was the one piece over which he had received the most criticism.

We agreed that it must have been the result of our common genes, allowing me insight when others failed."

In the next few years came ‘Energy’, ‘Fireworks’ and ‘Connotations’, a little later ‘Images’ and ‘Prague’ to the contest stage - each causing controversy and debate, whilst elsewhere we contentiously encountered the likes of Paul Patterson’s ‘Chromoscope’ and ‘Cataclysm’, Birtwistle’s ‘Grimethorpe Aria’ and Henze’s ‘Ragtimes and Habaneras’ for the first time.

They all however followed in the footsteps of the giant leap taken by Gilbert Vinter and ‘Spectrum’.

Iwan Fox

Original copies of the Spectrum score provided with permisison of Studio Music and Mark Coull.