Is the appetite for change now in the air?

Have you noticed how often the word ‘change’ crops up when it comes to the relevance of the competitive environment?

It’s the panacea buzz word to embrace a form of acceptable radicalism in politics to technology, fashion to sport.

Take the two great traditional sports of the English summer – cricket and tennis.

Time consuming

Despite England winning the World Cup, change is to come to the domestic game with the introduction of ‘The Hundred’ - a new limited-overs format aimed at an audience that finds the 50-over version, let alone Test matches, far too time consuming.

The purists are aghast, but as domestic cricket (largely not televised) is struggling to survive at County level throughout the country, ‘change’ was deemed necessary if a new generation of people (youngsters in particular) were to be attracted to the game.

The purists are aghast, but as domestic cricket (largely not televised) is struggling to survive at County level throughout the country, ‘change’ was deemed necessary if a new generation of people (youngsters in particular) were to be attracted to the game.

Meanwhile, in his ‘Final Whistle’ column in The Daily Telegraph, respected journalist Alan Tyers wrote that the All England Club’s Wimbledon sporting product, allied to BBC’s high profile broadcast schedule, meant that it retained its relevance and popularity in our consciousness, despite only taking up a fortnight of our time each year.

That has meant that the tennis administrators are quite happy to keep with tradition - although there was a tweak with the final set tie-break rule to ensure matches didn’t go on past the time when the strawberries and cream ran out in the Royal Box.

Domestic cricket is also played out to die hard enthusiasts

Where do contests fit?

So, where do brass band contests fit into the need for change? Are we cricket or tennis?

Well, it’s not a difficult question to answer.

In contesting terms (despite the sold-out British Open) we’re a form of County cricket spread over most of the year.

Like Country cricket, it is increasingly being played out to a diminishing number of diehard enthusiasts.

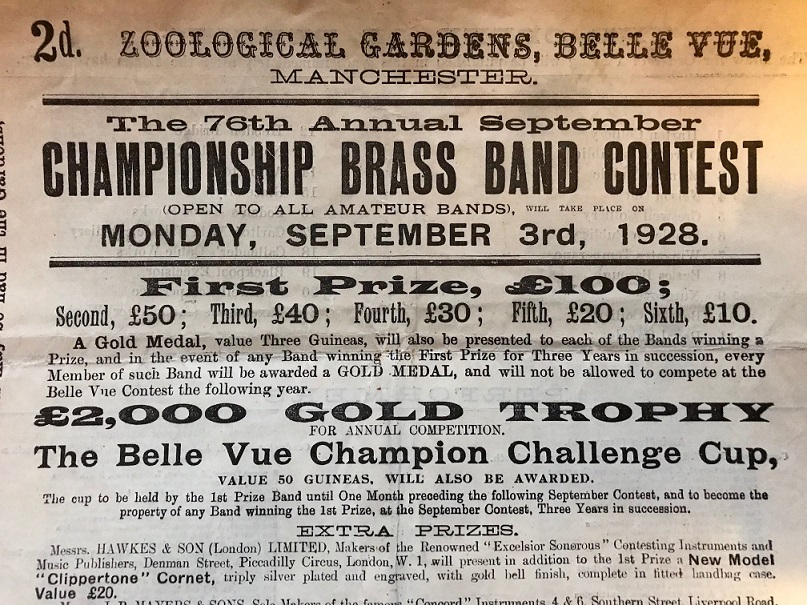

Contesting as an audience attraction hasn’t fundamentally changed for close on 170 years. Bands enter and turn up at the same time for a draw. The judges (mostly men) closet themselves away for a considerable period of time before eventually, the result (although rarely all of it) is announced.

Like Country cricket, it is increasingly being played out to a diminishing number of diehard enthusiasts.

And although technology has helped to relay scores and provide social media reports, fundamentally, what is so different about brass band contests in 2019 to those of 1919?

Embrace change?

So has the time come to finally embrace the need for change?

If it’s accepted that the contesting environment is one we have created for ourselves, then it can be argued that it’s of no consequence to anybody but ourselves how those events are run and managed.

Except that increasingly, if we choose to continue with our adjudicator boxes, our set pieces, our restrictions on player numbers, guest players, paltry prize money and any number of other rules that are ingrained in tablets of stone, the brass band contest, in its localised, domestic form at least, will soon become totally irrelevant.

Even the need for change will then have passed us by.

Tradition means some things haven't changed...

Stark questions

We therefore need to ask some stark questions.

How for instance do we persuade bands at every level to keep supporting these contests – especially ones whose long-term survival is linked to the dedication of an increasingly diminishing cohort of older enthusiasts – both organisers and listeners?

It is essential, as without contests at all levels, the very raison-d’être of many bands simply disappears.

And whilst that also asks pertinent questions about their own ability to embrace the need to ‘change’, perhaps a workable solution would be for both organisers and competitors to at first look towards a form of competitive ‘compromise’ rather than a radical overhaul.

A healthy debate is required then - one that encompasses the issues surrounding contest traditions that have remained sacrosanct for far too long, such as registration requirements; a necessity in eras of limited identity technology and a lack of social mobility, but increasingly anomalous today.

And whilst that also asks pertinent questions about their own ability to embrace the need to ‘change’, perhaps a workable solution would be for both organisers and competitors to at first look towards a form of competitive ‘compromise’ rather than a radical overhaul.

Bands can now register a player from Europe and fly them in for a contest weekend without breaking any rules, yet in the greater scheme of things, what actual long term benefit does that have for the band in question or the contest they are competing in?

A different era of trust in rules...

Registration

The registration system already has less traction with the growing trend for project bands - ones that primarily exist to compete at specific events, rather than to develop organically as musical organisations.

Why should they worry about concert performances and fund-raising events when they can compete by simply registering 28 or so players a set number of days before a contest, and then do the same with a different set of players for the next time they take to the stage.

It doesn’t break any rules – but there is no doubt, such an approach will kill off the relevance of many smaller domestic contests and perhaps even other bands that exist to embrace a very different musical philosophy.

Now, we are lucky to still have a solo and quartet contest attracting 20 or so players in total, an evening concert with more empty than full seats, and a well supported training day.

In my part of the world we used to enjoy an annual spring festival, featuring a four-section contest with upwards of 20 bands from around the country, followed by an evening concert attracting a near capacity audience. There were also two ‘county specific’ annual contests, a solo and quartet contest and even a rally of bands on the seafront at Great Yarmouth every July.

Now, we are lucky to still have a solo and quartet contest attracting 20 or so players in total, an evening concert with more empty than full seats, and a well supported training day.

It’s a microcosm of a long term domestic national decline - one that has been in need of change for far too long.

Why do some brass bands exist?

Fewer contests

Would we not be better off with fewer contests, reviewing where they are best placed to be held, pooling resources and enhancing prize money?

And what about examining whether the successful pyramid system introduced by the British Open, linked to other ‘qualification’ events could be utilised elsewhere to give more meaning and purpose to such contests?

The current state of the brass band contesting scene reminds me of the cliffs on the North Norfolk coast – gradually eroding away foot by foot, the incremental destruction now at a point that it has become too expensive for those in authority to consider halting.

Contest registration rules surely need to be reviewed in the same way – linking to other events that reward long term banding progression, rather than short term contest success.

None of this can be even considered, let alone achieved without a ‘change’ of mind set and an acceptance by those who give countless hours of their time voluntarily that the status quo is fast becoming an impossibility to maintain.

The current state of the brass band contesting scene reminds me of the cliffs on the North Norfolk coast – gradually eroding away foot by foot, the incremental destruction now at a point that it has become too expensive for those in authority to consider halting.

Small holiday homes and caravans fall away into the sea year after year – but as long as there is no historically important manor house, railway line or road under direct threat, there is little outcry and appetite to change the course of direction.

So should we allow the erosion of our contesting coastline to continue and see the numbers of competing bands at smaller events fade away, or can we get together and come up with a long term plan for ‘change’ that embraces the tradition but in a new forward thinking way?

Idea sharing and cooperation

Surely it’s time for Brass Bands England, the Scottish Brass Band Association and the three Welsh bodies (and Northern Ireland) to engage in idea sharing and cooperation.

Moreover, so should the six English Regional Committees and their Welsh counterparts (and the Scots), the British Open, National Championships, Butlins, Brass in Concert and other major contest promoters (without losing their independence).

Perhaps the forthcoming Brass Bands England Conference on 28th September at the Life Centre, in Greater Manchester is the place for the debate to begin.

The afternoon will feature a lively panel discussion, on the question of 'What is the purpose of Brass Band Contests?'

If cricket can do it in asking the question of how it can remain relevant and progressive by trying something new when it is enjoying a rare moment in the national spotlight, then surely brass bands (with the forthcoming Sky Arts series and recent BBC 1 features) can do the same.

The time for change has come.

Tim Mutum