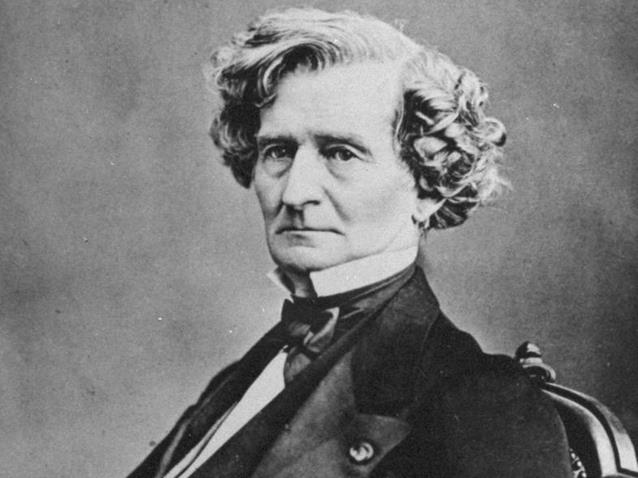

A lean, mean sculpting machine... Benvenuto Cellini

The competing bands at this year’s Butlins Mineworkers Festival will be faced with a very particular test of musical character.

No blockbusters or special one-off commissions, nothing arcane or squeaky-gate esoteric; just simple, old-fashioned brass band overtures.

It’s a clever idea by Stan Lippeatt and the Butlins team - especially given that the festival takes place just two weeks into the New Year when carol-bruised lips have returned to action from a short break bathing in the Epsom Salts of various alcoholic libations.

The selections may be short in length but they still pack a heavyweight punch.

And what the band’s pick may well give a pretty good indication of not just the level of their physical preparedness, but also of their ambition in trying to claim a share of the generous cash prizes on offer.

Championship trio

The Championship Section trio of ‘Benvenuto Cellini’, ‘Carnival’ and ‘Rienzi’ are a case in point.

On the Mohs scale of test-piece hardness Frank Wright’s arrangement of Berlioz’s overture to his 1838 opera about the 16th century Italian goldsmith and sculptor who also happened to be a murderer, braggart and adventurer is on the diamond edge of things.

There is a reason why it hasn’t been heard very often since it was used at the 1970 World Championships.

As one famous brass band conductor once said: “There are two problems with ‘Benvenuto Cellini’. One - it’s rock hard. Two: You rarely get to the second because of the first.”

As one famous brass band conductor once said: “There are two problems with ‘Benvenuto Cellini’. One - it’s rock hard. Two: You rarely get to the second because of the first.”

It’s a compact beast of a piece; lean, meaty and ferocious - 11 and half minutes or so of stamina-sapping playing that leaves well-flogged cornet players in particular with trout-pout lips as if they’ve overdosed on Botox injections.

Many have tried, but few have really tamed it with a comfortable sense of macho braggadocio.

Qualsiasi acquirente then?

Carnival capers anyone?

Carnival

‘Carnival’ isn’t too far behind either.

Dvorak wrote it in 1891 as part of a trilogy celebrating ‘Nature, Life and Love’ - and although it has no operatic connection it stands as one of the most vibrant examples of the overture genre.

Geoffrey Brand’s florid arrangement was commissioned for the 1980 National Finals, and although just 10 minutes or so in duration it’s a technical tour-de-force (especially when it heads into Cb - 7 flat territory) that’s exceptionally difficult to keep on a tight adrenaline-fuelled leash.

It will leave fingers burnt, whilst the tambourine player could also suffer from repetitive strain injury by its close.

Upstanding citizen

That leaves the curiosity that is Haydn Johns’ arrangement of Wagner’s ‘Rienzi’ - who unlike Benvenuto Cellini was a more upstanding citizen of Rome.

Written in 1835, the opera tells the tale of the Tribune who took on the corruption of the nobles only to find popular opinion turn against him and his fate sealed with his final words: “May the town be accursed and destroyed!”

With that a building falls on his head.

Much was made in 2005 of the way in which its ‘turns’ should be played at the ‘Areas’ - but that was more an academic ‘amuse bouche’ than anything else on Howard Lorriman’s arrangement which had a bit more colour and depth than this 1962 take.

Much was made in 2005 of the way in which its ‘turns’ should be played at the ‘Areas’ - but that was more an academic ‘amuse bouche’ than anything else on Howard Lorriman’s arrangement which had a bit more colour and depth than this 1962 take.

Mr John clearly marks his score - so there shouldn’t be any quibbles - although in comparison to the other demanding arrangements this one is 11 and half minutes of standard top-flight fayre.

So which one do the seven bands pick?

Be adventurous and go for the Tuscan goldsmith or the ‘Carnival’ flamboyance, or play safe with a touch of Wagner pomposity?

Hector's house or Destiny's child...

Destiny or clarity?

The First Section conductors have also been given a test of ambition with the familiar showcase overtures ‘La Forza Del Destino’ and ‘Le Corsaire’.

Both are celebrated arrangements - the Verdi (1962) by Frank Wright and the Berlioz (1969) by Geoffrey Brand - and each having lasted the test of time in terms of the challenges they pose.

‘The Corsair’ is the more ensemble orientated take - although Berlioz’s (above) own tempo marking of 152 is on the cusp of technical sensibility.

As indicated on the brass band score, it also comes with an advisory warning: ‘Conductors should exercise discretion and not allow speed to overrule clarity’.

How many will take note we wonder?

As indicated on the brass band score, it also comes with an advisory warning: ‘Conductors should exercise discretion and not allow speed to overrule clarity’.

Expertly paced

The same applies to the more ornate soloistic splendour of ‘The Force of Destiny’ - which can quickly lose its dramatic pulse though questionable tempo decisions.

If any conductor is in doubt of how to expertly pace the eight and half minutes then they should seek out the classic recording of CWS (Manchester) from 1962 or Black Dyke (with Jimmy Shepherd rattling off the ‘Allegro brillante’ triplets like peas fired onto tin sheeting from a machine gun) live from the Albert Hall in 1972.

Neither lack for drama or brilliance if played with the respect they deserve.

Burp and bubble from Aristophanes frogs

Frogs and students

Two very different takes on the overture form face competitors in the Second Section, with Brahms ‘Academic Festival Overture’ and Bantock’s ‘The Frogs of Aristophanes’.

Brahms self-congratulatory work was written in 1880 after he had been awarded an honorary doctorate in philosophy from the University of Breslau.

It also has a sly sense of humour - the ‘academic’ themes come from student songs, although the structure is scholastically crafted, especially in the counterpoint finale.

Denis Wright’s arrangement retains the same ethos - cultured and light, but still asking questions of pace, dynamic and balance.

Burp and bubble

In contrast, Aristophanes’ ‘Frogs’ bubble and burp in a chorus in what is only the briefest of appearances in the underworld tale of Dionysus trying to bring the playwright Euripides back from the dead.

Bantock’s ‘comedy’ overture from 1935 is a by-product of his symphony ‘The Cyprian Goddess’ - although like many of his literary inspired works, there is no actual narrative theme.

It is however a wonderful curiosity of invention, cross rhythms and compound time; dark, animated and mysterious.

In contrast, Aristophanes’ ‘Frogs’ bubble and burp in a chorus in what is only the briefest of appearances in the underworld tale of Dionysus trying to bring back the playwright Euripides back from the dead.

Britannia rules the waves?

Patriotism and national identity

Works of patriotism and national identity pose the problems in the Third Section, with Beethoven’s ‘Egmont’ and William Rimmer’s ‘Rule Britannia’.

Given Britain’s problems with all things Brexit, Beethoven’s incidental music celebrating the life and heroism of Lamoral, Count of Egmont in his fight against French oppression might just tickle the fancy.

Eric Ball’s 1949 arrangement is a crafted piece of workmanship - the considered scoring allowing clarity and balance, even if it sounds a touch monochrome with its colour palette.

Rimmer’s ‘Patriotic Overture’ also has colour - although it’s been yellowed by age like the nicotine stained fingers of Homer Simpson’s sisters in law, Selma and Patty .

Apposite

Meanwhile, Rimmer’s sprightly take on Thomas Arne’s music, itself set to the words of James Thomson, and which include the famous refrain; ‘Rule, Britannia. Britannia rules the waves’, is also oddly apposite given the current ‘crisis’ of a few desperate people trying to cross the English Channel only to be met by a form of gunboat diplomacy.

Rimmer’s ‘Patriotic Overture’ also has colour - although it’s been yellowed by age like the nicotine stained fingers of Homer Simpson’s sisters in law, Selma and Patty .

Exhumed from the contesting crypt (it was last used at national event in 1965) it’s a curious amalgam of styles; from a majestic opening to ‘one in a bar’ quick waltz (marked to deter any sea-borne invaders as ‘Come if you Dare’) with a curious cadenza for the horn to bridge into the thematic refrain and ride for home.

The stark beauty of Saddleworth

Colour and drama

There are contrasting ‘overtures’ to be heard in the Fourth Section - although neither have an operatic inspiration but do contain plenty of thematic colour and excitement.

Eric Hughes wrote ‘Overture to Youth’ in 1976 for a music competition sponsored by the now long defunct National School Brass Band Association and Dynatron Radio Ltd. He came fourth.

An engineer and accomplished jazz pianist, Hughes cleverly structured his three-movement linked work; the first, opening slowly featuring the rare occurrence of not one, but two BBb tuba solos before developing into a ‘spirited’ representation of youth.

A rather mournful lyrical middle section marked ‘rubato e expressive’ should allow more than a little soloistic licence before the tempo is lifted in ‘Allegro Vivace’ finale with its loose thematic reiteration of the main theme.

An engineer and accomplished jazz pianist, Hughes cleverly structured his three-movement linked work; the first, opening slowly featuring the rare occurrence of not one, but two BBb tuba solos before developing into a ‘spirited’ representation of youth.

Twins

Goff Richards’ ‘Saddleworth Festival Overture’ has been used at this event before (2013) but still maintains its upbeat challenge, despite being written 36 years ago as part of the twinning celebrations of Saddleworth in England and Saddleworth in Australia.

That explains why some of the thematic material cleverly encompasses everything from ‘Pratty Flowers’ and ‘Hail Smiling Morn’ to ‘Waltzing Matilda’ and ‘Advance Australia Fair’.

Otherwise it would be an introduction to an opera that would have been completely bonkers.

Then again, most of them are; so why not simply enjoy the great tunes.

Iwan Fox