In an exclusive article for 4BR, its arranger Paul Hindmarsh gives an insight into a suite that has come from music originally composed for a 1937 BBC radio drama.

King Arthur - Scenes from a radio drama (arr Paul Hindmarsh)

1. Overture: Fanfare, Coronation and Wild Dance

2. Galahad, Merlin’s Spell and the Holy Grail

3. Lancelot and Arthur

4. The Death of Arthur: Doom, Battles and Apotheosis

Benjamin Britten was about eight years old when he began to compose. We know just how prodigiously gifted and productive he was because the music he wrote as a child he himself preserved for posterity.

There are reams of short pieces for the piano (his instrument), copious songs, pieces involving violin and viola (which he also played) and a number of string quartets and orchestral pieces - but nothing for brass.

As a teenager, ‘Benjie’ was encouraged by his mentor, the composer Frank Bridge (1979 - 1941), whom he visited for composition lessons in the school holidays, to think through the instruments he was using, especially the strings and to a lesser extent the woodwinds.

From his teens to his 60s, Britten’s command of string textures was formidable; exhibiting a peerless technique, imagination and refinement.

The composer...

Probably the closest he got to experiencing brass at close quarters was on Lowestoft’s South Pier bandstand, just around the corner from the family home. And whilst his writing for brass instruments never reached the same elevated level as that for strings, there are moments of true brass genius, especially in the masterworks of his later years.

There he used the full orchestral brass for its reinforcing power, but early on seemed reluctant to deploy individual instruments outside their traditional context - as a provider of fanfares, marches or jazzy moments. The huge quantities of music he supplied at top speed for the GPO film unit, several left-wing theatre companies and the BBC certainly sharpened his skills in this area.

Best appreciated

How the mature Britten viewed the capacity and character of brass instruments can perhaps be best appreciated in his ‘Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra’ (1944), in which the dexterous trumpet material derives from fanfare intervals, the trombones are bold and heroic, the tubas both humorous and lugubrious and the French horns subtler and more refined in sonority.

The majestic tutti brass sounds in the fugue command our attention, as they do in his opera, ‘Gloriana’ (1953). The pomp and pageantry of Elizabeth I’s progress through Norwich in the opening scene is brilliantly conveyed in a high tempo dance measure on the full brass based on conventional fanfare material.

How the mature Britten viewed the capacity and character of brass instruments can perhaps be best appreciated in his ‘Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra’ (1944), in which the dexterous trumpet material derives from fanfare intervals, the trombones are bold and heroic, the tubas both humorous and lugubrious and the French horns subtler and more refined in sonority.

As Britten’s later music became increasingly transparent in texture and economical in detail, he also began to exploit brass technique and sonority with greater originality and freedom, as in the ‘Fanfare for St. Edmundsbury’ (1959).

The symphonic ensemble fanfare at the start of the ‘Dies Irae’ in ‘A War Requiem’ (1961) is every bit as bold and visceral as the passage in Verdi’s ‘Requiem’ that clearly inspired it. The transformation of fanfare to lament in the setting of Wilfred Owen’s ‘Bugles’s Sang’ that follows the ‘Dies Irae’ is truly inspired.

‘Fanfare for DW’ (1969) is in essence a lively three-minute overture for brass based on favourite operatic moments of its dedicatee David Webster. The brass band adaptation I made was performed by Black Dyke at the 2013 RNCM Brass Band Festival.

Exotic writing

Best of all, perhaps, is the ‘exotic’ writing for alto trombone and D trumpet in two of his Church Parables; ‘The Burning Fiery Furnace’ (1966), and ‘The Prodigal Son’ (1968), as well as the woodwind and brass fanfares Britten composed for the prelude to his television opera ‘Owen Wingrave’ (1970), and the lilting brassy overture of his final opera, ‘Death in Venice’ (1973).

A youthful Benjamin Britten

In one sense, Britten came full circle with the composition ‘Death in Venice’, because the transparency of the part writing harks back to the method, if not the sound that he adopted in his film and theatre scores, drawing maximum effect from a limited palette of colour and thematic content.

Listen to any of his orchestral scores from the 1930s to the 70s and you’ll hear what makes his orchestral sound world immediately recognisable.

Like Prokofiev, he lets his string textures breathe, using doubled octaves sparingly except for the big climaxes and special sonorous moments - as in ‘Peter Grimes’.

This feature limits, for me, the number of works of Britten’s that lend themselves to a comfortable realisation on brass band, without excessive breaking of lines or phrases. The texture is likely to become too compressed.

Appropriate for brass

However, I have come across a few less heralded pieces where brass and wood wind dominate the sound because of the subject matter, thus making brass band versions more appropriate.

Once such is the music he wrote for a radio drama based on the life of King Arthur that I came across while researching a series for BBC Radio 3, ‘Britten’s Radio Music’ (1995).

BBC radio was in its infancy when Britten began broadcasting as pianist and composer in the 1930s, during which the Corporation became a major influence on the cultural life of the country, encouraging leading composers and writers to develop innovative ways of combining words and music.

Among the pioneering assistants (or producers) tasked with inventing these programmes were Scottish writer and poet Douglas Geoffrey Bridson (1910 - 1980) and actor and director Val Gielgud (1900 - 1981), elder brother of John Gielgud, who was appointed Head of Productions in 1929. Between 1946 and 1952 his influence was directed towards the fledgling BBC television drama department.

BBC radio was in its infancy when Britten began broadcasting as pianist and composer in the 1930s, during which the Corporation became a major influence on the cultural life of the country, encouraging leading composers and writers to develop innovative ways of combining words and music.

In the spring of 1937, 23-year old Britten was approached to compose the music for a re-telling of the life and times of King Arthur and his Court, written by D.G. Bridson. Britten was actually Bridson's third choice composer for the project; Arnold Bax and Rutland Boughton having declined the commission.

The nearest Britten came to brass? In 2013 the Royal Mint issued a commemorative 50p piece

He was not long out of the Royal College of Music - but had already come to the attention of the musical establishment with a number of publications and significant London performances to his name.

Top speed

‘King Arthur’ was the first of no fewer than 28 scores which Britten delivered to the BBC over the subsequent decade.

He produced the music at top speed - like a film score, during March and April. It was ready just in time for the live broadcast performance on 23rd April (St. George's Day) 1937, shortly before the coronation of George V the following month.

Bridson was delighted with the contribution of the young composer, who noted in his diary that the music, “…certainly comes off like hell!”

A distinguished cast for this 90-minute epic included a young Michael Redgrave as King Arthur. The broadcast was directed by Val Gielgud with the music performed by the BBC Chorus and the London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Clarence Raybould.

Bridson was delighted with the contribution of the young composer, who noted in his diary that the music, “…certainly comes off like hell!”

The drama - part pageant, part play and part cantata - was laid out in 18 scenes; beginning with Arthur’s coronation and concluding with the final fateful battle.

Britten enjoyed true international fame

Each scene was prefaced by narrative verse in the style of Sir Thomas Malory’s ‘Le Morte d’Arthur’ (1485). Britten was less than enthusiastic about Bridson’s script, which he considered dull, stilted and uninspiring, “…a pale pastiche of Malory” he added in his diary.

Like every demon in hell

The score comprises 22 musical items of varying lengths and substance involving vocal soloists, choir and orchestra. For the 1995 BBC Radio 3 series I prepared a 25-minute orchestral suite, organising the most substantial items and some unused sketch material into four symphonically proportioned movements.

It was recorded by the BBC Philharmonic conducted by Richard Hickox and released on Chandos CHAN 9487. In 2014, I fulfilled a long-held personal ambition of fashioning some of this dramatic brassy music into a second much more concise suite for brass band.

I selected purely orchestral cues requiring minimal manipulation, other than some occasional transposition down an octave to ‘fit’ onto the band.

For the most part I followed the narrative sequence except for a ‘Wild Dance’, in which all the jealousies and intrigues at Arthur’s court erupt ‘like every demon in hell’, as the script tells us.

I didn’t need to leave any musical lines out. My overriding concern was to create a coherent structure with sufficient contrast.

Narrative sequence

For the most part I followed the narrative sequence except for a ‘Wild Dance’, in which all the jealousies and intrigues at Arthur’s court erupt ‘like every demon in hell’, as the script tells us.

Britten reused this spectacular virtuosic music in his ‘Ballad of Heroes’ (Op.14). I’ve placed it as the second part of an ‘Overture’, offering a challenging workout for cornet soloists and horns, with an important role for soprano cornet. This is set against a repeating bass line, which I have muted, mirroring the light, athletic sound of pizzicato strings in the orchestral score.

Call to Arms

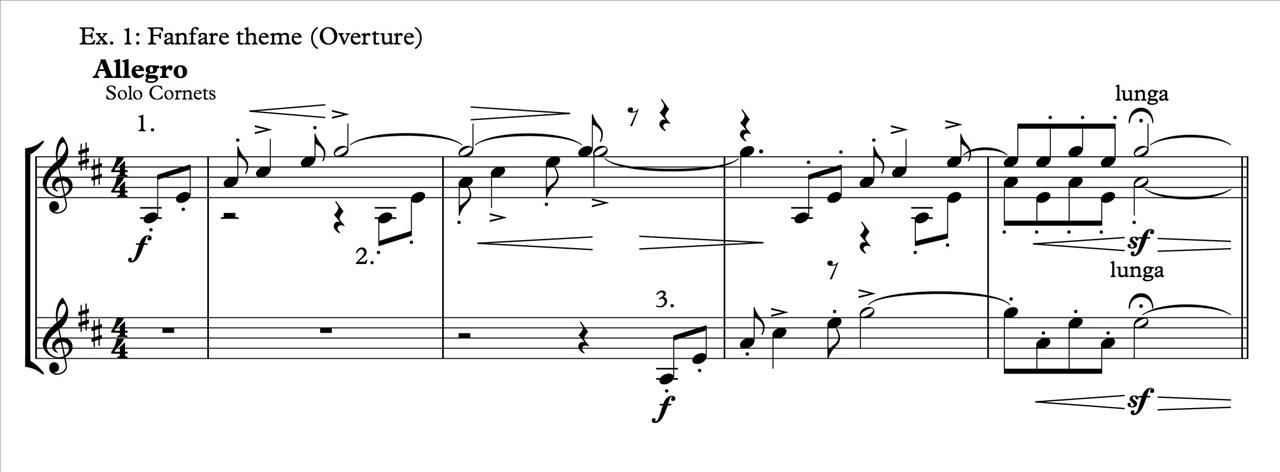

‘Scenes from a radio drama’ is announced with a ceremonial ‘Fanfare for Tourney’ , the score’s principal ‘call to arms’ motif founded on a dominant seventh [Ex. 1].

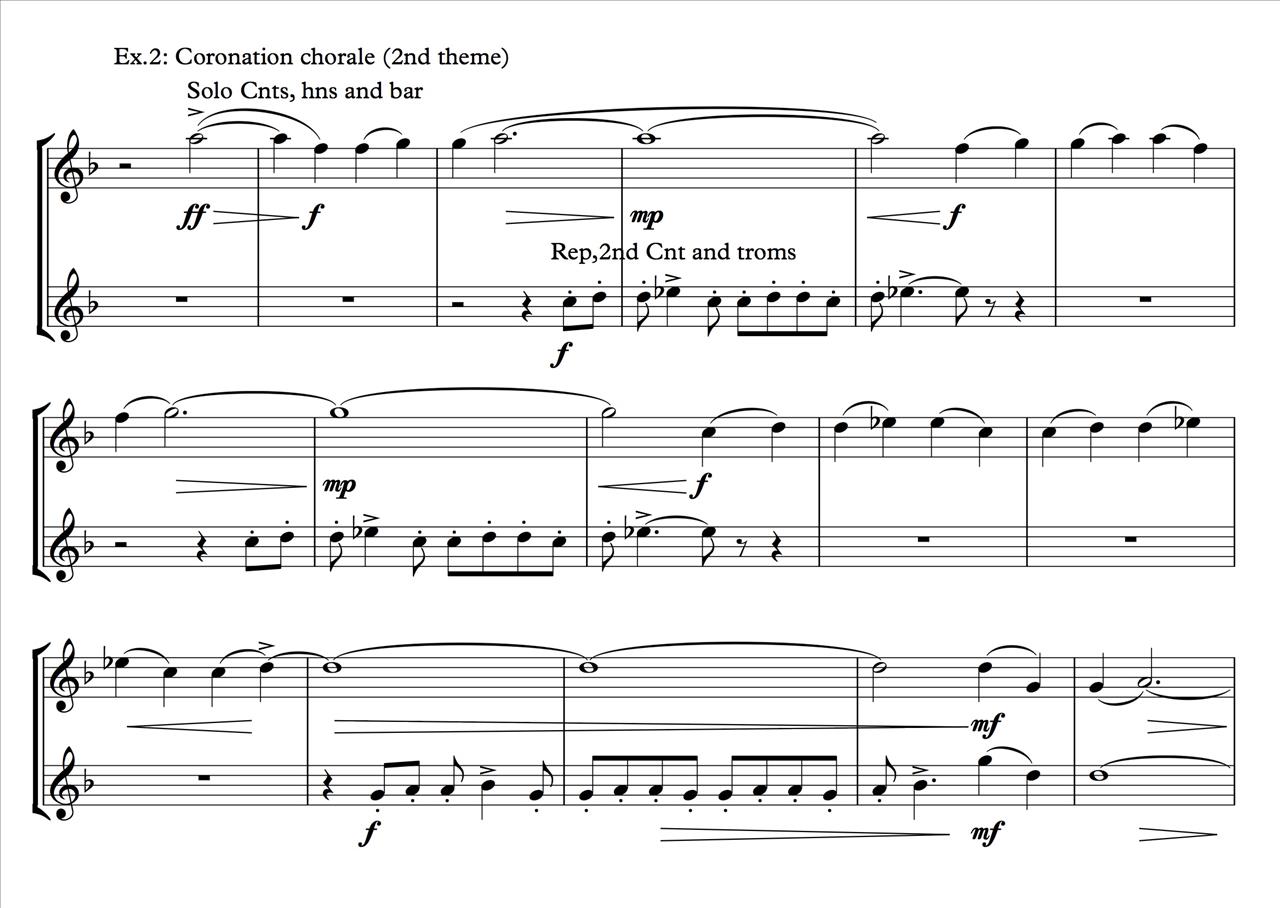

This leads directly to Britten’s short introduction, Arthur’s ‘Coronation’ scene, announcing a second more extended hymn-like theme, which Britten associates throughout the work with Arthur himself [Ex. 2].

A bridge passage for originally the French horn becomes a high-wire cadenza ‘moment’ for solo euphonium connecting Coronation scene to the ‘Wild Dance’.

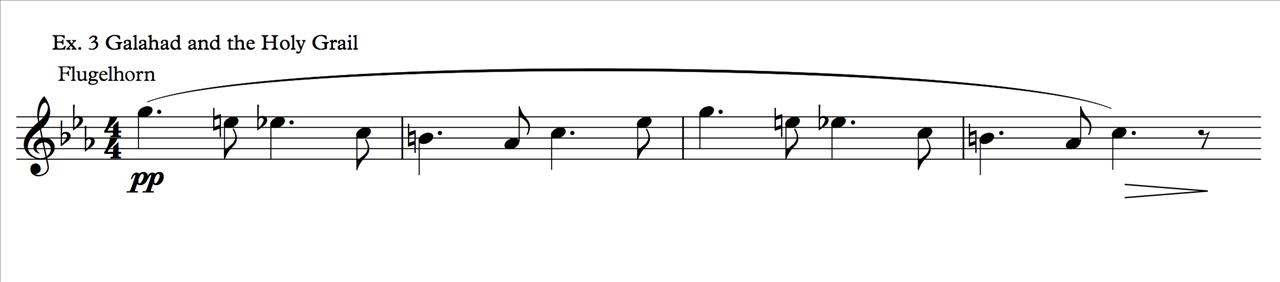

The second movement, ‘Galahad and the Holy Grail’, links three musically related scenes underscoring Galahad, Merlin's spell and a vision of the Holy Grail.

They are all based on a lyrical subject derived in its sinuous arpeggiated line (mixing major and minor thirds) from the fanfare motif [Ex. 3.].

Flugel, soprano and solo cornet are challenged to show off their subtle expressive skills in a lyrical middle section. Britten reused the melody as the theme of a replacement slow movement for his 'Piano Concerto' (Op. 13).

The fanfare variant which they support is a portent of the brutal battle music that follows. Here, the two main themes are set against each other to fight for supremacy.

Because of time constraints, the third movement, comprising a ‘Galloping’ sequence for percussion and ‘Death Music’ lamenting those lost in the first battle, is not being played at the Cheltenham finals on 16th September.

Instead the Holy Grail music links to a sombre sequence of chords appropriately titled 'Doom Music' by Britten.

The fanfare variant which they support is a portent of the brutal battle music that follows. Here, the two main themes are set against each other to fight for supremacy.

Arthur's death

I have brought together the two battles scenes from Acts 2 and 4, which is Arthur’s last and fateful battle, building to a searing climax.

The moment of Arthur’s death and the lament are vividly captured by the composer. There is plenty of deft detail to be negotiated amid the heat and noise of battle, which recedes to an almost cinematic Apotheosis, ‘Down the pathway of th’immortal waters’, and Arthur’s final journey to Avalon.

Paul Hindmarsh

‘King Arthur, Scenes from a radio drama’ is published under license in the Faber Music Band Series by permission of Chester Music and the Britten Estate. http://www.fabermusicstore.com