The master curator painting his own musical pictures...

Howard Snell’s masterful ‘Gallery’ is a work of personal impressions and individual imaginations.

Six pictures (five for this contest) of various styles and age, linked by nothing other than the stimulation of the mind - his as well as yours.

It is dedicated to two Scottish musicians who in the composer’s words, “taught me the value of determination and hard graft”, and through being “…generous of time and insight, opened my young ears to the great composers and what they were saying.”

He has done Bert Mackay from Paisley and John Erskine of the Royal Scottish Junior Academy, proud. Everyone will surely leave the Royal Albert Hall better informed as well as thoroughly satisfied by this particular artistic experience.

Thought provoking choices

Howard Snell would make one heck of a gallery curator. His choices are eclectic and thought provoking, immediately transparent and engaging. They invite scrutiny, debate and rich enjoyment.

However, it is also his own work that places substantive demands on conductors to seek a level of authenticity to their approach to his score. His compositional brush-work offers little compromise - its provenance unmistakable and inviolate.

Those persuaded to tamper with their contest day hangings things will surely reveal their clumsy attempts at pastiglia camouflage

Those persuaded to tamper with their contest day hangings will surely reveal their clumsy attempts at pastiglia camouflage (especially with the composer joined by Philip McCann and Luc Vertommen in the box). The seating plan, although flexible to an extent, is also a form of deliberately created sound canvas; allowing the chiaroscuro textures and subtle transparencies to be heard through precisely defined pacing and forensic dynamic detail.

Not even forgers as good as Tom Keating or Shaun Greenhalgh could get away with anything on this one.

Opening stroll

The work opens with a short stroll through the gallery entrance, with the intriguing ‘Comodo’ directive perhaps indicating that the viewer (the opening soprano cornet in this case) is already somewhat familiar with the surroundings. There are no wasted moments in the gift shop here.

They know where they are going; comfortable and relaxed as marked - certainly not enquiring or apprehensive in any way, leading into a final bar with its unresolved decision making - right or left, upstairs or straight ahead? It is a perfectly crafted moment of ‘where to then?’ expectation.

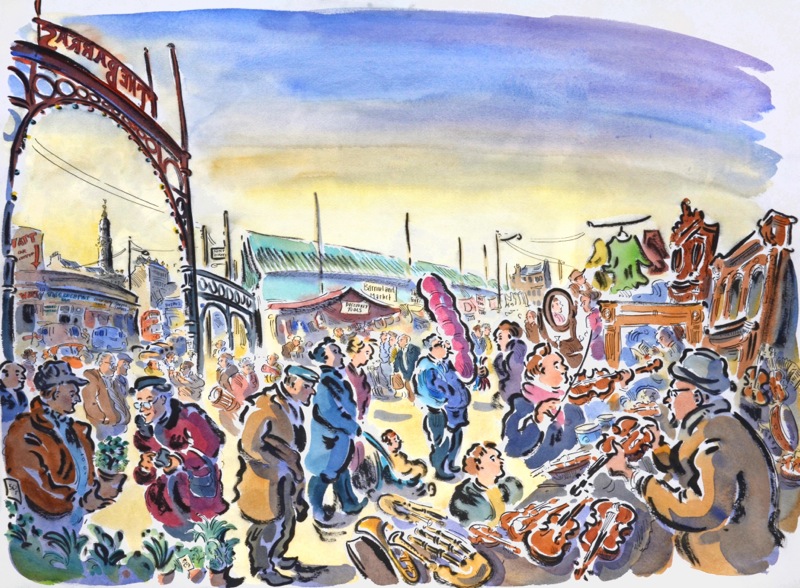

The Barras by Paul Cox

The choice is ‘The Barras’ by Paul Cox.

Painted in 1991, it depicts the famously rambunctious Glasgow street market, packed with its traders and customers, bubbling with colour, vibrancy and life.

Working class commerce

It’s a portrait of working class commerce - almost Dickensian in character, yet with an edgy warmth of welcoming inclusion. Amid the bric-a-brac and cheap clothing there are stalls selling musical instruments, flowers, family antiques and produce from all around the world.

Snell captures the raw intimacy of the bustling brightness; the shouts and haggles, the occasional arguments and sharp edged clamour.

The detail is specific and witty; mixing subtle sleight of hand with gestures of grandeur without ever ripping people off.

The detail is specific and witty; mixing subtle sleight of hand with gestures of grandeur without ever ripping people off. There is a joyous feel of enterprise and entrepreneurial energy - ‘Barra Boys’ making good.

Softly comedic

It is followed by ‘The Skater’s Waltz’ - a softly comedic portrait of the Rev Robert Walker on Duddingston Loch, painted by Henry Raeburn in 1784, and better known by the colloquial title, ‘The Skating Minister’.

It hangs in the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh, and is wonderful snapshot of a Church of Scotland Minister enjoying (although his countenance is one of stoic determination) a rare day off from his flock (there is no one else is sight).

Stoic Godly determination: The Skating Minister by Henry Raeburn

Walker was a proficient early version of Robin Cousins - although Snell has fun with his impression of a Godly man occasionally falling foul of the science of gravity.

The music is flowing (c.168) yet occasionally awkward and splay-footed, as the good Reverend finds trouble with the icy marbles under his feet - grabbing at thin air (the solo cornet in triplet mode) before regaining his composure and confidence to showcase his talents at speed.

As he takes his leave it ends with a delicate, witty reminder to him in the form of a tiny flugel triplet, of the sinful attributes of pride coming before a fall.

As he takes his leave it ends with a delicate, witty reminder to him in the form of a tiny flugel triplet, of the sinful attributes of pride coming before a fall.

Romantic soul

The time constraints of 20 performances unfortunately means we do not get to hear ‘The March back to Camp’ inspired by the tragically moving portrait ‘Gassed’ by John Slinger Sargent, although it does allow the beautifully crafted ‘Love Story’, based on Caitriona Campbell’s ‘Old Couple’ to seep deeper into your romantic soul.

There have been many famous paintings of husbands and wives in art history; from van Eyck’s ‘Arnolfinis’ and Gainsborough’s ‘Mr and Mrs Andrews’, to Grant Wood’s ‘American Gothic’ - portraits that ask questions of power, prestige and possession.

In contrast Snell has picked a wonderfully contemporary portrait of elderly love; two inconsequential looking figures tiredly walking hand in hand (perhaps even away from the gallery itself).

A pair of touching inconsequential figures

There is no Arnolfini display of ostentatious prestige here (they wear plain utilitarian coats), whilst any youthful power the man once had has long been diminished by the use of a walking stick. You can believe the only valuable possessions they have on them are the sandwiches that may be in the woman’s well worn handbag.

You can believe the only valuable possessions they have on them are the sandwiches that may be in the woman’s well worn handbag.

The overwhelming sense though is of an endearingly touching, (both physically and metaphorically), life-long love – enhanced by the composer’s beautiful writing which has a yearning, non-sentimental expressiveness that combines acceptance and familiarity with tender but now, all too distant passion.

It ends as if you are catching a last glimpse of the couple walking into the damp mist of a Glasgow evening.

The esoteric delights of Matisse

All that jazz

What follows is jazz - and the wonderful cut-outs Henri Matisse created during the period 1936 to 1954.

Snell revels in the colour, effect and dislocation of form, exuberantly portraying the dazzling creations with a brilliantly defined sense of style. Hints of Millhaud’s ‘Scaramouche’ come to mind as the vibrant hues are mixed with subtle nuance and bold expressionism to hit you between the eyes.

Snell revels in the colour, effect and dislocation of form, exuberantly portraying the dazzling creations with a brilliantly defined sense of style.

It may well be hard to hear it all in the vast echoing barn that is the Albert Hall (it is marked at 144), but the sheer joie-de vivre, pulsating energy and the swaggering, sashaying plunder draws you in. It closes with an explosive certainty of forceful imperious confidence.

Grand vistas to close

It leads us to the final portrait - and the grand bucolic vistas of Ben Lomond by John Knox.

Full of declamatory splendour and Highland majesty, it’s a sweeping, almost imperial climax - all Edwin Landseer’s ‘Monarch of the Glen’ stuff, with its echoes of the opening thematic material reminding the listener of those first few steps taken into the gallery itself.

You leave with your entrance expectations completely fulfilled - and totally uplifted by the whole experience.

Iwan Fox