Romantic memorials sometimes hide the reality...

Despite the modern day tendency to romanticise the memorialisation of the mining industry, the brutal reality has always been one of loss.

Personal, collective, communal: The capriciously destructive influence of both man and nature has always been the omnipotent, ultimately horrific accompaniment to the extraction of coal from deep beneath the surface of the earth.

The lingering effects still resonate around the world today; from distant memories of individual family bereavement to the names of villages whose timeless identity will forever be associated with unimaginable mourning; Senghenydd in Wales, Benxihu in China, Coalbrook in South Africa, Dhandad in India, Monongah in the USA. It is a long and stark statistical obituary.

Bleached headstones

Thousands upon thousands have been killed - including the 116 children and 28 adults submerged by the wave of colliery mining waste that engulfed Pantglas Junior School in Aberfan on the morning of 21st October 1966.

It is not the romantic notion displayed by sunken pit wheels, painted coal trams and shiny brass gift shop miner’s lamps that recall the story of the true of cost of mining coal - but the cold rows of bleached headstones that fill graveyards in proud communities across the globe.

The outstanding work comes from the pen of Thierry Deleruyelle

It is that reality that informs Thierry Deleuyelle’s outstanding composition ‘Fraternity’ - an intensely thoughtful work that recalls one such horrific disaster; that of Courrieres near Lens in Northern France in 1906, when 1099 miners were killed by an explosion of coal dust. It remains the second largest loss of life in the history of the industry.

Connection

There is personal connection for the composer – his paternal grandfather was a miner from the age of 12 in the type of pits that formed the focal point of villages such as Mericourt, Sallaumines, Billy-Montigny and Noyelles-sous-Lens that were to be denuded of a generation of proud husbands, fathers and sons.

There is personal connection for the composer – his paternal grandfather was a miner from the age of 12 in the type of pits that formed the focal point of villages such as Mericourt, Sallaumines, Billy-Montigny and Noyelles-sous-Lens that were to be denuded of a generation of proud husbands, fathers and sons.

Written as the set-work for the 2016 European Brass Band Championships in Lille, it is an unfolding, Joycean tone poem - one that retells, without recourse to misplaced emotion, the timeline of a single catastrophic day and its immediate aftermath.

However, it is also a powerful exploration of the binding sense of fraternal identification that led miners from as far afield as Belgium and Germany to come to offer assistance in the task of both rescuing survivors and in bringing out the dead.

The hellish heart of the extraction of coal

Seven linked sections form the narrative chapters of the 10th March 1906; opening with the dawn rituals of personal preparation and the unworldly, icy mystery of the men’s trek to work, as the imposing triangular edifice of the colliery tower slowly emerges from the damp mist of the early morning.

The layered music unfolds with a deliberate sense of tension and unease – revealing the palpable sense of foreboding of what fate is soon to bestow upon them. The euphonium is the lead voice, the tubas the shadow figures of colleagues heading to their collective destination.

Fraternal dialogue

Into the gullet of the shaft the miners drop like stones to the pit floor – some 340 meters below the surface; the simple cornet solo increasing in intensity and extremis as the cage finally hits pit bottom; a fraternal dialogue between the baritone and horn leading the men to the coal face.

Here they arrive at the truly unromantic heart of industrialised mining life - and the hours of laborious, rhythmic extraction of coal amid hellish conditions; picks, hammers and shovels working in a unified cause.

Here they arrive at the truly unromantic heart of industrialised mining life - and the hours of laborious, rhythmic extraction of coal amid hellish conditions; picks, hammers and shovels working in a unified cause.

The deliberate low pitched passagalian foundation that pulsates with intensity is matched by the mechanical sounds of the percussion and the busy interjections of the higher brass as the coal is ripped, jagged-edged from the rich seams.

There are hints of unimaginable forces though – touches of Paul Dukas and ‘The Sorcerer’s Apprentice’ as the miners burrow with increasing ferocity, ever deeper into the dark arteries. The music here is full of controlled detail, purpose and precision – yet still one false move away from disaster.

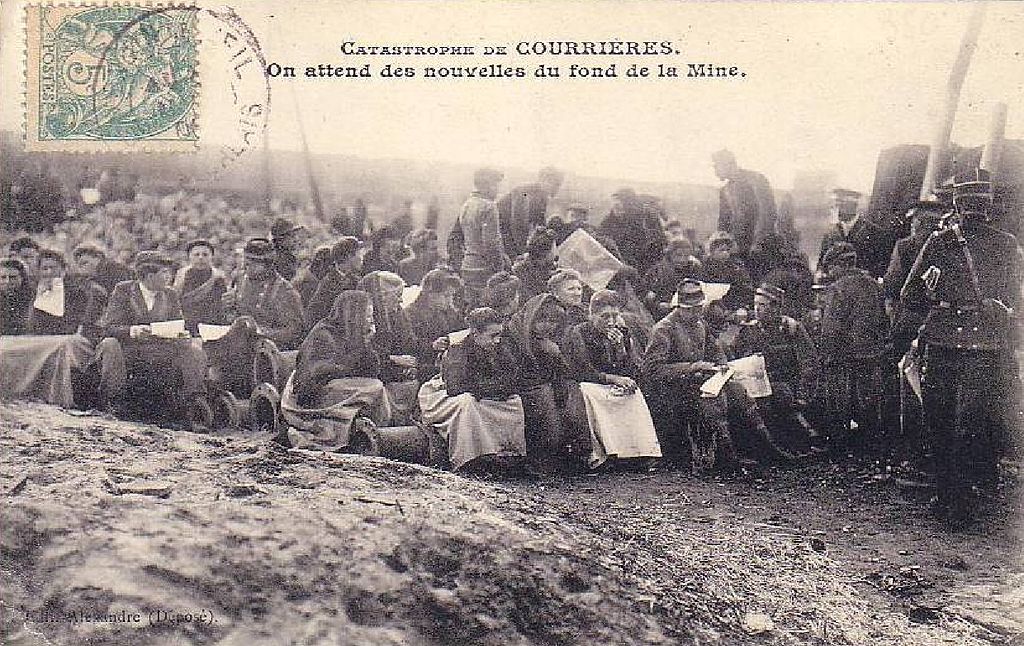

A French postcard from 1906 showing the families waiting for news at the pit

It comes; a ripping ferocity of explosive slaughter that blasts its way through the tunnels and walkways obliterating humanity in its wake – the heated percussion forcing the music forward before the bubbling semi-quaver undercurrents of gas bring chaotic mayhem.

The music has a chilling inhumanity; stabbing fissures emerging from almost nowhere to suck air from lungs, small elemental motifs and fleeing semi-quaver runs signalling life or death throughout the ensemble as panic sets in.

The music has a chilling inhumanity; stabbing fissures emerging from almost nowhere to suck air from lungs, small elemental motifs and fleeing semi-quaver runs signalling life or death throughout the ensemble as panic sets in.

Paean of grief

Eventually, the force loses its destructive energy and ebbs to a funereal close. A deathly tuba chord heralds the task of bringing out the dead; the timpani motif evoking the same early morning ritual of preparation and journey – although this time the anticipation is filled with an overwhelming feeling of loss.

Above ground the realisation of what has occurred is heralded by the simple paean of grief from the solo cornet - a prayer joined in melancholic recitation by an ever increasing ensemble.

It is touching, sombre, dignified. The intensity grows as the bodies of those lost are finally laid to rest and the community draws on the fraternal bonds of friendship and solidarity to stand together as one.

The work closes in hope rather than desolation.

Iwan Fox