As with the first article in the series, I’ve followed the debate around the ‘quality’ of music being written for the brass band medium - a concern voiced by Philip Harper and others that many new works being written are not of a high enough standard.

It raises a point that I think has been missing from these discussions - that of a sense of context: What aesthetic benchmarks can we use to measure ‘quality’ - especially from the classical music world?

Not to denigrate

I will choose a defining brass band work from each decade of the 20th century and into the new millennium since the first ‘original’ brass band contest composition was used in 1913 - and offer up a very different orchestral masterpiece written around the same period of time.

I do not seek to denigrate the brass band composition in question at all - far from it.

Three steps ahead

What I do hope it shows however is that at the time the brass band movement may have believed it was embracing new compositional spheres of influence, the rest of the musical world was already three steps ahead.

It will also perhaps give a taste of what compositional possibilities may have been explored if these outside influences had been fully or even partially embraced.

I’ll give the briefest of introductions to the work and a few things to listen out for.

Read part 1

What might have been? The first 50 years of lost compositional opportunities

http://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2016/1577.asp

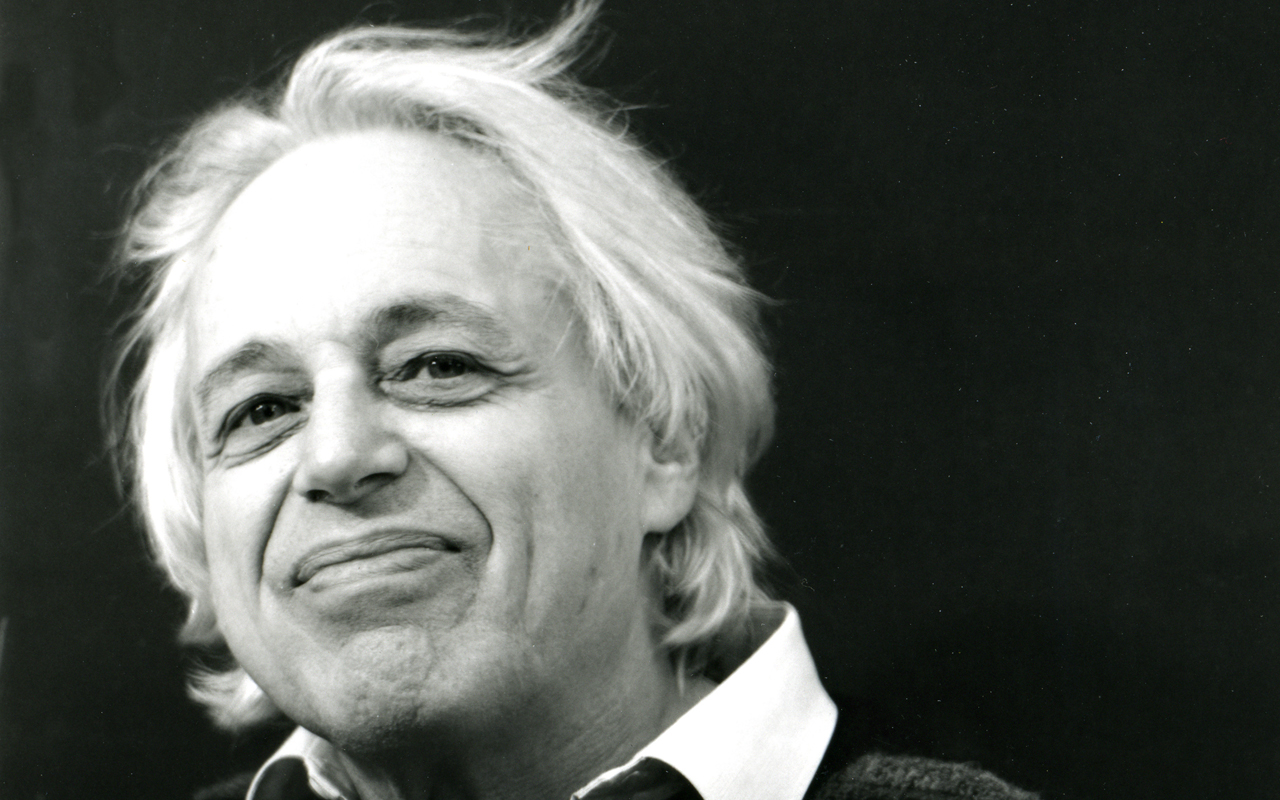

György Ligeti

Spectrum (Gilbert Vinter) [1969]

Atmospheres (György Ligeti) [1961]

Despite it now being considered a ‘classic’, when ‘Spectrum’ was premiered at the British Open Championship in 1969 the reaction to it, both before and after it was performed, was largely negative.

This inexplicable outrage to a composition that was considered out of the ‘norm’ has unfortunately become a little too familiar over the years: ‘Fireworks’, ‘Images’, ‘Prague’, ‘The Maunsell Forts’ and ‘Muckle Flugga’, amongst others have since been castigated.

How different it may have been if people had heard more works by composers such as György Ligeti (1923 – 2006) - or perhaps knew that they already had.

His ‘Atmospheres’ was written eight years before the whirling, kaleidoscopic opening to ‘Spectrum’ was heard at the King’s Hall in Belle Vue. By then however, Ligeti’s music had already been included in Stanley Kubrick’s iconic ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ in 1968, the first of many films that would include his scores.

In ‘Atmospheres’ Ligeti explores a technique he developed called micropolyphony - essentially polyphony but using much denser lines and complex rhythms so that the overall effect is one of rich sonorities and dense, undulating textures.

Scored for a large orchestra, minus percussion, there are no big tunes here, or audible counterpoint - but rather vast swathes of slowly moving chords that come to the foreground and disappear again.

It’s utterly beguiling and hypnotic.

Spectrum:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KbRXM3EFx8g

Atmospheres:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DJ70FjT6eTg

Gérard Grisey

Connotations (Edward Gregson) [1977]

Partiels (Gérard Grisey) [1975]

‘Connotations’ is still rightly considered to be one of Gregson’s finest works, and in many ways it is a piece that heralded the start of a new era in brass band composition.

This was a score that not only demanded so much technically from the players, but also introduced a new, sparser musical language to the ‘post-romantic’ literature that had dominated until it was heard at the National Finals.

It is interesting to note that just a few years before, Heaton’s ‘Contest Music’ had been rejected for the same contest, replaced by Hubert Bath’s ‘Freedom’: The importance therefore of ‘Connotations’ cannot be underestimated.

Around the same time in France, a very different composer was paving the way for a very different type of music: spectralism.

‘Partiels’ is part of a cycle of works by Gérard Grisey (1946 - 1998) called ‘Les Espaces Acoustiques’ - and is an extraordinary work for 18 musicians, full of strangely electronic sounds (all created by acoustic instruments) and a certain amount of theatrics.

At its end the players noisily put their instruments away and a lone cymbal player is left in spotlight ready to crash them together before the stage is plunged into darkness.

The opening of the piece is particularly arresting; based on a sonogram analysis of a single note - a trombone pedal E.

Grisey then orchestrates the harmonic partials derived from this note throughout the orchestra. You could perhaps say the piece is in E major, but it’s the most spectacular E major you are ever likely to hear.

Connotations:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PWO7fzFzSyw

Partiels:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1v7onrjN6RE

Mark-Anthony Turnage

English Heritage (George Lloyd) [1988]

Three Screaming Popes (Mark-Anthony Turnage) [1988-89]

George Lloyd (1913 – 1998) wrote a number of successful works for brass band and, while his music was considered by some as regressive, the brass band world found his tonal, melodic style appealing - even though his orchestral output was largely ignored by the likes of the BBC for many years.

‘English Heritage’ was written towards the end of his life and is rather typical of his output; an engagaing work that, despite its title (English Heritage refers to the Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England that commissioned the work), is quite modern - by brass band standards - but still looked back.

Around the same time however, a young composer was pushing British music into a new age.

Mark-Anthony Turnage (1960) quickly became somewhat known as the ‘bad boy’ of classical music after writing a series of daring and original orchestral works. These scores were full of an energetic drive and expressive lyricism that was a breath of fresh air to the contemporary new music scene in the UK.

Chief amongst these is ‘Three Screaming Popes’ - written straight after his ground-breaking opera, ‘Greek’. It is also a work inspired by a very different artistic take on the heritage of portraiture - and the famous re-interpretations by Francis Bacon of the paintings of Pope Innocent X by Diego Velazquez.

It is music full of the expressive lines, jazz infused melodies and driving rhythmic dances that have become so characteristic of his music. There are echoes of Birtwistle and Stravinsky, yet the music is distinctive, characterful and textured.

English Heritage:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aAWTqvtjwQ0

Three Screaming Popes:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HMWSy9mfxSs

Jonathan Harvey

…Dove Descending (Philip Wilby) [1999]

Tranquil Abiding (Jonathan Harvey) [1998]

‘…Dove Descending’ was commissioned for the British Open Championships and, following in the footsteps some of Wilby’s previous works such as ‘The New Jerusalem’, ‘Dance Before the Lord’ and ‘Revelation’, has a deep seated Christian belief at its core.

Conversely, Jonathan Harvey’s (1939 - 2012) output is wide and varied, but spirituality, particularly Buddhism, is often a central feature of his works.

‘Tranquil Abiding’ is a Buddhist term for a state of single-pointed concentration and at the opening of the work Harvey scores a kind of musical version of deep breathing: inhalation (crescendo) and then exhalation (diminuendo); a breath ‘In’ on a higher pitch and then a breath ‘out’ on a lower pitch.

This slow inhaling-exhaling motif underpins the entirety of this piece before finally coming to rest on a magical ppp Db major chord on muted divisi strings.

In its way there is a connection between the composers and their musical inspiration – although their interpretation of faith is very different indeed. Both however are beguiling in their ability to make it relevant and engrossing.

…Dove Descending:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aBl72MSozfw

Tranquil Abiding extract:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MpdLz5DPdns