Chris Thomas: How did your relationship with the Jones & Crossland Band begin?

Stephen Roberts: That really stemmed from being with Fine Arts at university. Roy Curran had left the post of conductor of J & C and Andy and Bryan played with the band.

Andy had been principal cornet with them since it started at the Birmingham Conservatoire so he suggested I do an audition. I had already some experience as a conductor of amateur orchestra and choirs and through my session work.

I also worked a lot with Simon Rattle and learnt much about rehearsing from him.

I adapted an arrangement of ‘Londonderry Air’ that I had done for a television session for the Fine Arts.

Bryan loaned me a score of one of Gordon Langford’s arrangements so I could see how a band was laid out.

I didn’t know what a baritone was, but I remember saying, “....you on the curly instruments over there need to be a bit louder”, or some such.

Anyhow I got the job!

Chris Thomas: You were blessed with some terrific players - including Owen Slade, Andy Fawbert, Andy Culshaw and Bryan Allen.

That must have been like a dream come true given that they were the first band you had conducted on a regular basis?

Stephen Roberts: Not to mention Mark David on front row, Carole Crompton on baritone and Bryan Hurdley on euphonium! They were a great band and we were all young.

I think only one person was over 30 and that was Brian Bunting who so tragically died.

I went into the band scene as a sort of ingénue. I just thought all bands were like that and it was like having a big quintet. A quintet with knobs on!

Actually your question prompted me to look at that the Brass Band Results website and I see that of the first 22 contests we came 1st in ten (there is one contest not on the site) and were placed in four others. Quite a good record!

An older Image: The Jones & Crossland Band

Chris Thomas: Many old timers (myself included!) remember vividly the stunning winning performance of ‘Images’ at the Midland Area Championships in 1980 from the number one draw.

What do you remember of that performance and the furore surrounding the piece?

Stephen Roberts: We had a gig with Fine Arts that evening and had to opt for the number 1 spot.

Some of the players were annoyed, saying nobody won from that draw. I was naïve. I thought that if we played best we would win regardless. Happily (or luckily) I was proven right!

The piece was ‘up my street’.

I love new music and I was doing a thesis on the early quarter-tone music of Pierre Boulez at that time. John’s piece seemed very conventional by comparison and I couldn’t understand what all the fuss was about.

Iconoclastic: Michael Tippett

Chris Thomas: Another memorable performance was Michael Tippett’s ‘Festal Brass with Blues’ at the Granada Band of the Year in 1984, a bold musical statement if ever there was one!

What was behind the decision to play the piece on that particular platform?

Stephen Roberts: Well, once again, I don’t understand what is difficult about this music!

We all enjoyed the piece and thought it good to listen to. We thought others should like it too and not be hidebound about tastes and traditions. We all agreed to do the piece as an iconoclastic gesture really.

You have to remember that at that time even my version of the ‘Teddy Bears Picnic’ was considered ‘new’ in terms of conventional repertoire! In addition it also reflected some of the Fine Arts’ ideas about new music.

We always included new and ‘difficult’ pieces in our programmes and mostly audiences were glad to hear them.

Simon Rattle had the same idea for the CBSO concerts (I used to play with them a lot) and the audiences grew to like these new ideas.

We tended to reject the more mainstream, clichéd composers who had nothing original to say.

New sounds and new faces: Stephen Roberts with the Pontins Trophy

Chris Thomas: Do you feel that brass band audiences have become more receptive to new sounds and contemporary music in general over the years?

Stephen Roberts: Definitely, but there is still a way to go and band audiences could be more open-minded.

But one has to remember that banding is essentially a culture of the people, not comprising solely professional musicians or cast as an elitist pastime.

It’s not about the intelligentsia. In many ways that is what I love about it.

There is no doubt, though, that there is too much rubbishy pastiche around and it looks narrow-minded from outside the band bubble.

People tend to be afraid of the unknown but I think it would be wonderful if bands could always schedule at least one unknown or new work.

It’s a shame they no longer broadcast the regular band programme on Radio 3.

Broadcasters: Jones & Crossland take to the airwaves

The trouble is that many composers characterise the brass band as a special medium, like fifes and drums or bagpipes (heavens forfend!).

The result is that bands get overlooked or even avoided by many composers outside the band fraternity. There is a danger, too, that the only time band audiences hear new music is at contests.

I’m not totally convinced this is the best platform for what you might term ‘art’ music. We need more festivals to celebrate new music for band so composers can throw off their shackles and be free to write what they want.

Composing competitions are another way, of course, and it’s good to see these giving talented young people opportunities.

The trouble with the contest piece as a genre is that it usually has to please the audience, so that can stop composers seeking new horizons.

On the other hand many composers find constraints paradoxically liberating and you only have to look at Heaton’s ‘Contest Music’ or McCabe’s ‘Cloudcatcher Fells’ to see that it can be done effectively.

It is also plain that ‘pure’ works like Ireland’s ‘Comedy Overture’ or Ball’s ‘Journey to Freedom’ still represent a good test and a good listen. Philip Wilby keeps doing it well too.

In a nutshell it’s all about musical integrity.

As Keats said – 'a thing of beauty is a joy forever' - and that applies to test pieces!

Chris Thomas: Composition has always been a part of your musical life but in recent years you have written a number of major works for high profile orchestras and ensembles including the BBC National Orchestra of Wales and the Britten Sinfonia.

Do you have plans for further works in this sphere?

Stephen Roberts: I’m a pragmatist. I tend not to write unless I’m asked and I like to write music for a specific occasion but I’ve usually got something on the go.

I’ve just finished a ballet for the English String Orchestra and I have been recording sessions with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment who are recording my reconstructions of Mozart’s unfinished horn concertos on period instruments. In December I have a choral work being premiered.

I have always been involved in a broad spectrum of the musical profession and I don’t really pigeon-hole what I do.

Like Alfred Schnittke (the Russian composer) I am a ‘polystylist’ and see no problem in juxtaposing opposing musical styles or genres.

When I completed my PHD, a long while ago now, it was part of my brief to explain the apparent variety of styles in my submitted portfolio.

At first I thought I had to justify it, but that imperative helped me realise that that was my style – I don’t like to repeat myself, I am always searching for something new.

Chris Thomas: Your original music spans a wide variety of styles. Where do you draw your inspiration from?

Stephen Roberts: That depends on the type of piece. If it’s to be light or tonal it just comes out, but if it is to be a serious piece of ‘art’ music it can be a long process setting out the musical ‘rules’.

Once I have an idea I tend to write very quickly, but the struggle is the IDEA!

It may be a chord or note series or a motif that sticks. Generally it is connected to the instruments involved. Sometimes, as with my piece for the Britten Sinfonia ‘The next stop is ….Angel’ it may be an experience.

In that case it was a virus of the brain that caused terrible vertigo. My ‘Sinfonia for Brass, Percussion & Strings’ looked back to early music and filtered it through a sequence of gradual tonal breakdown.

More importantly a serious work needs to be multi-dimensional and so there are often several ideas, both musical and philosophical, developing concurrently.

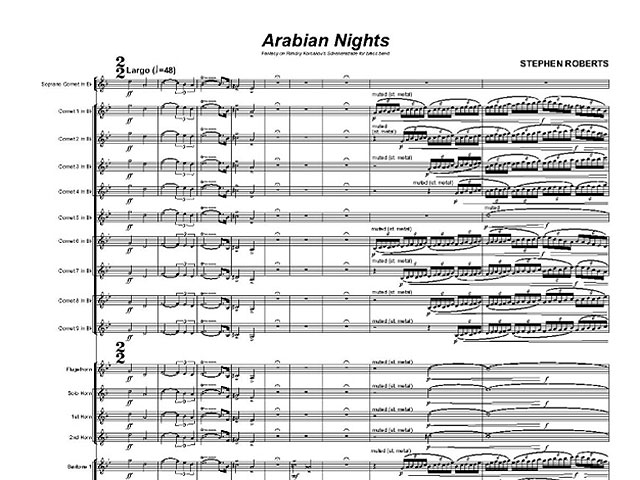

Arabian Nights in Birmingham this year....

Chris Thomas: Although you’ve written numerous pieces for band including ‘World Dances’ for youth band, what we haven’t had from you until now is a large-scale serious work or test piece to rank alongside your orchestral pieces!

Would you relish the opportunity to write further ones?

Stephen Roberts: Absolutely! I have lots of ideas.

However you won’t have to wait too long for the first as I have done the test piece for the British Open of course.

‘Arabian Nights’ is a fantasy rather than an outright composition. By fantasy I mean an arrangement with compositional bells and whistles, not wishful thinking!!

I have also orchestrated my 20-minute ‘Euphonium Concerto’ for brass band and that is still waiting to be premiered.

Steven Mead has done a wonderful recording of it with the RAF Central Band. That is a piece which sits in between my lighter works and my serious orchestral ones and I am pleased with the result.

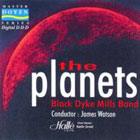

Chris Thomas: Your landmark arrangement of ‘The Planets’ ranks amongst the most ambitious arrangements ever undertaken for band.

What drove you to take on such a monumental project?

Stephen Roberts: It was Nick Childs’ idea as a recording project for his Doyen label.

Holst had gone temporarily out of copyright but was due to go back into copyright because of the new EU 70 year law.

Black Dyke hadn’t qualified for the Nationals so they wanted to do something to take its place in October of that year – oh, it must have been 1991, I think.

I was about to go on holiday and Nick phoned with the idea, but I wasn’t too keen because I had to cut my holiday short to do it in time. Anyhow I agreed and came home early and had two weeks to do it in.

For the second week I had to look after my four-year-old son because my wife was away on tour (she is a viola player). I had to make Lego models each day to distract him and then creep to the Atari ST with its Notator software before he got bored with the model.

I did it from a tiny miniature score and I remember taking that up to a rehearsal at Queensbury and David King being very amused that I hadn’t got a decent copy!

Like you, David said, “Why did you do it?”

I could only reply, “Because I was asked.”

Anyhow the project was abandoned and it wasn’t until several years later that Jim Watson recorded it.

Chris Thomas: You’ve become increasingly prominent as an adjudicator at major contests in recent years.

Stephen Roberts: Sitting in a box for hours on end isn’t everyone’s idea of fun but do you enjoy the experience?

Fun isn’t quite the word, but there’s a lot of camaraderie in the ‘box’, even so.

It’s a privilege in some ways. You learn so much from it, but it also appeals to the didact in me.

I think you have two roles; firstly to get the results right and secondly to help those that haven’t succeeded by pointing out their strengths and weaknesses.

I see contests as festivals of excellence and they are in many ways the lifeblood of brass bands. They maintain standards and create aspirations.

In or out of the box with the judges...

Chris Thomas: Having experienced open adjudication at the Scottish Open a couple of years ago is your preference for open or closed adjudication and why?

Stephen Roberts: I wrote an article for 4BR some years back strongly advocating closed adjudication.

There is no doubt that you cannot help being influenced by what you see on stage.

On the other hand at the Scottish contests the open adjudication made little difference because there wasn’t time to look as you spend the whole time writing observations against the score.

I think there is still a strong case for closed adjudication at the ‘top’ contests because of the perceived fame, or standing, of the best bands.

It’s an old chestnut, but most people who are experienced at adjudicating are confident that the closed system is fairest. Personally I am happy to do it either way, but I’m not keen on box-ticking.

I have used this method for diplomas and degrees, as well as job interviews, and I think it is flawed and sterile.

It takes away the didactic process and the reliving of the piece through vicarious commentaries.

Chris Thomas: You’ve recently been involved with a CD of your music by Fodens Band released by the Swiss company Difem who now handle the distribution of your music.

Stephen Roberts: Will you be continuing to self-publish under your own established banner of Tanglewind Music?

Difem act as distributors of Tanglewind Music, so I can still maintain my intellectual property rights or copyright.

They have taken a few smaller publishing houses under their wing to expand their business in a bid to stem the tide of the ever-expanding American publishers.

They have some good stuff on their books and they can also help by funding recordings, which is something I cannot afford to do.

The new CD I did with Foden’s, ‘A Portrait of Stephen Roberts’, is an example.

In exchange I have written some new commercial arrangements under the Difem banner.

It is a symbiotic relationship which seems to be going well, but the Difem name is not so well known in this country so I urge everyone to remember it!! DIFEM!! [shouts] DIFEM!!

Chris Thomas: You have also been closely involved with English Symphony Orchestra in the capacity of Associate Conductor in recent years, an orchestra that you know well from your freelance playing days.

Apart from giving you a little relief from banding is orchestral conducting something that you plan to further expand on in the future?

Stephen Roberts: Orchestral conducting is a very closed shop. Like many things in my life I have more or less fallen into doing these things so I haven’t made grand plans.

Much of the conducting I have done has stemmed from directing my own scores, be it in the recording studio or on stage.

I would actually like to do more band conducting since I have a more regular life-style now. I’m open to offers!

Orchestration and Arranging....

Chris Thomas: Without wishing to remind you, 2012 has been the year of your 60th birthday!

With such a diverse musical career covering all aspects of the profession, do you still have any ambitions and objectives left to fulfil?

Stephen Roberts: I have to be busy with some project or another.

I am currently writing a book on ‘Orchestration & Arranging’, amongst other things.

But age is irrelevant as far as I am concerned. That’s one of the great things about the music business: age, class, race and gender are never issues as a rule.

Musicians are doctors of the soul, as the ancient Greeks acknowledged.

As long as I am actively engaged in some sort of music-making and it is good quality, I am happy. I think, though, it is important for me to perform – you just don’t get the same feedback as a composer because often you don’t even know about the performance.

Many years ago I promoted my own Christmas concert.

I funded it, gave interviews on the radio and placed adverts in the newspapers, booked the hall and players, did all the artwork for the publicity, wrote the music, printed the parts and posters, conducted it, set up the stage, put up the Christmas tree, wrote and designed the programmes which acted as lottery tickets, bought the prizes, dressed up as Father Christmas and wandered round the town to publicize the event and even dressed up as Santa again as ‘guest conductor’ during the concert.

I also narrated my own setting of the ‘Night Before Christmas’ whilst conducting it and playing the horn.

Furthermore I played synthesiser and set up the sound system and supplied the music stands.

The next day I couldn’t move – I don’t think I have ever been so exhausted, but I had a sort of sense of achievement in that I had done every single part of the performance, from concept to execution.

However, I won’t be doing it again!!!

Chris Thomas: Thanks Stephen - and we look forward to hearing your British Open test piece at Symphony Hall.

Part 1 of the Stephen Roberts interview: www.4barsrest.com/articles/2013/1374.asp#.UZthhLVOR8E