The recent debates sparked by comments over Paul Lovatt Cooper’s (below right) 'Breath of Souls' (the test piece for the 2011 National Championships) have, for me, lacked any form of meaningful conclusion.

With some of the movement’s heavyweights weighing in to the debate, I have found it remarkably surprising to hear of some of their comments and views.

Bereft

Bereft

At a time when individuals in the brass band world find themselves almost bereft of an aesthetic compass, many of our supposed brightest and best have failed to offer us anything enlightening, turning instead into sycophants demanding that we curb our critical thinking.

Here, I discuss what I believe is really at stake in this whole debate; why composers sometimes seem so heavily at odds with conductors, listeners, performers, and each other.

Music is not just ear candy.

It is inherently imbued with a potent sensual appeal; this is obvious to anyone.

What is less obvious is music’s capacity to tell us something about ourselves and the world in which we live.

Dialogic

Music is what I would call dialogic.

It enters into a dialogue with us – just like other art forms, like theatre and painting. It speaks to us, but also speaks of us and the times we live through.

Challenge and comment

Since the late 19th century, the notion that art should challenge, critique and comment on the status quo has been with us as much in painting as it has in music.

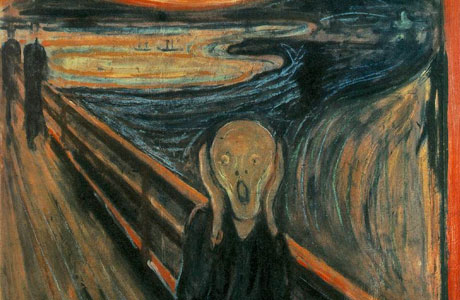

Edvard Munch’s famous 1889 representation, ‘The Scream’, (below) was a stark move away from the impressionist movement that preceded it.

This was a painting that did not seek to recreate the beauty of the world. It sought to give voice to the inner angst of a world heading towards the abyss.

This was one of the earliest examples of expressionism in painting: The screaming figure in the foreground screams in agony, both hands wrapped around the face in a contorted release of a tortured inner self.

Music follows art

Music and art have been ideologically close throughout history, so it wasn’t long before music began to follow art in its aims and content.

Schoenberg (below right), Webern and Berg all began exploring music’s capacity to give voice to man’s inner self.

The result was music that was often shocking in content and abrasive in performance.

No longer an option

No longer an option

For many composers tonality was no longer a viable option – expressionism demanded a ‘stream of conscious’ approach, allowing composition to proceed naturally, unhindered by the forms and techniques of a previous age.

This was music that spoke of the time – of the doom and gloom in the years approaching the First World War.

This was also music that commented on the techniques and forms associated with tonality, questioning their fitness for purpose in an entirely new (and frightening) world.

Second Viennese school

Since the dramatic tabula rasa of the second Viennese school, many musical ideologies have negotiated a tumultuous co-existence.

One set of ideas was closely tied to music’s new found capacity to embody and express feelings and attitudes towards a time, a place, a zeitgeist.

Music tool

In this sense, music was almost a tool for composers to express certain ideologies that may or may not have been solely for the benefit of a listener.

This was music that said something. That said, a second set of ideas has always been present.

I would argue that this second set has dominated the world of performed music, culminating in the ultimate celebration of indulgence in the 1960s with the emergence of ‘pop’.

Function of music

The function of music here relies on its ability to entertain, please, move and celebrate. This is music for the masses; music that one can ‘listen to’ (as if one is somehow unable to listen to other music) and enjoy, offering pure sensory pleasure (in whatever form).

Music historians frequently paint a picture of music history whereby tonality collapses around the start of the 20th century, and atonality (or altered forms of tonality) takes over.

This belies the fact that tonality did indeed continue, and was fervently lapped up by audiences everywhere.

Whether it was the latest Puccini (right) opera or the swing music of the roaring twenties, tonality continued to exist, and so did the need to entertain.

Never involved

Never involved

The brass band movement was never involved in music’s ideological transformations. It never claimed to be. Perhaps we have never truly been aware of how music outside the brass band setting has changed.

The movement itself was always far more concerned with entertainment, pomp and circumstance, and, of course, celebration.

Brass bands frequently performed programmes with myriad content; musical menus designed to please even the most diverse of audiences: Solos with a ‘good tune’, arrangements, hymns, overtures, and many other favourites appeared as light musical libations in an evening’s entertainment.

Many concerts still follow a similar pattern, but things have changed a lot now.

Growing validity

The growing validity of the brass band as an ensemble (and I’m referring here to perceptions of the ensemble outside the brass band world itself), has caused an unforeseen conflict.

Over the last few years we’ve become accustomed to the many ‘superstars’ who have propelled instruments like the tenor horn and the euphonium (such as David Childs - right) onto stages across the globe as solo instruments with their own unique properties.

These instruments are no longer ‘band instruments’. They are now much more able to stand up on their own as legitimate solo instruments outside the brass band setting.

Contesting role

Contesting role

Contesting has also had a significant role to play.

Music written to challenge performers now dominates even our most prestigious competitions, resulting in contest music that would pose difficulties for even the finest professional players.

It is the rise of the superstar culture coupled with the enormous demands placed on brass band players on the contesting stage that has raised the standards not only of music making, but of music composition.

Why write music for an ensemble that can’t play it?

For composers, this is now seldom a problem when considering writing for band, and music that pushes the boundaries is seldom easy……

Radical shift

We have thus seen a radical shift in the music being written for the medium itself, and we now find ourselves supporting the two the musical trajectories I mentioned earlier.

It is not only entertainment and contest music that is being written for brass bands nowadays, but also music that pursues a more ‘progressive’ goal.

Music that pushes the boundaries, that finds new modes of expression, is perhaps something that we find most difficult to deal with.

By the standards of modern musical scholarship, however, it should be considered equally as valid as music that simply ‘entertains’.

Pushing boundaries

Composers are no longer writing music solely for entertainment or the satisfaction of contest-winning criteria.

They are writing music that very deliberately seeks to push the boundaries of musical expression, speaks of the world into which it is born, and challenges the status quo.

One would imagine that the acquisition of the status of an ensemble ‘worthy’ of serving as a vehicle for an aesthetic trajectory previously reserved for the symphony orchestra would be hugely satisfying for those who we regard as being ‘leaders’ of our movement.

Unsure

Clearly, however, they are themselves unsure of how to regard this shift in status. I’ve heard numerous individuals berate composers (and others) who have questioned the motives of Paul Lovatt-Cooper in 'Breath of Souls'.

Many have responded by suggesting that the critics are ‘jealous’ of his success, that they are simply exhibiting the proverbial ‘sour grapes’.

For me, this is a response that is indicative of a misunderstanding of many composers with slightly different aspirations in their music.

Popularity at the Albert Hall this year...

Lack of affinity

The co-existence of two separate aesthetic ideologies in music has never been a wholly peaceful one. The lack of affinity between these them has been frequently and very overtly recognised and negotiated in the public sphere.

As we begin to embrace the brass band’s involvement in musical aesthetics in the 21st century, we must accept several things.

Talked about

First of all, music is dialogic, and something that we all talk about.

It is an art form, which fosters a plethora of opinions, both positive and negative.

Just like the latest trials and tribulations of our favourite football teams or celebrity gossip – we talk about it.

We live in a free democracy where we enjoy the freedom of being able to hold and express opinions that differ from those around us. We should never be asked to curb our opinions on such things.

Prejudice

For individuals in our movement to berate people for expressing an opinion about an art form is like berating someone for expressing a dislike for truffles or caviar.

Such statements tell us more about the prejudices of those doing the berating than those being berated.

In addition, in true postmodern vein, we must realise that those we consider some of the foremost individuals in the brass band movement should not be seen as arbiters of taste.

This is entirely subjective.

We must not simply say we like something because somebody famous does. We must be true to ourselves, because our true opinions on music (often unlike the music itself) are scarcely political.

Legitimacy

My point is that as the brass band gains legitimacy as an ensemble capable of supporting numerous aesthetic trajectories in music, we must expect the criticism and debate to become more polarised.

How frequently does one read harsh reviews from classical music critics in our national newspapers? I suggest, practically every day.

If composers are to put their music out on show, they must expect to receive criticism and applause in equal measure, especially when the polarity between musical ideologies becomes increasingly evident in the music of the brass band movement itself.

Come of age

Whether our music entertains or pushes the boundaries, whether it celebrates tonality or ridicules it, whether it challenges us or indulges us, we must be prepared to accept that the brass band as a medium has come of age.

It now flexes its muscles as an ensemble capable of furthering more aesthetic agendas than perhaps we initially thought possible. It doesn’t simply bring us pleasure any more, but it brings us music that challenges us and pushes the boundaries of what is possible and conventional.

Open ourselves up

We must accept that composers who write music that appeals to our senses will always have a place in the brass band movement.

We must, however, also open ourselves up to the challenges and intentions of music that we would not normally expect to hear at a brass band concert, by composers who align themselves with an aesthetic trajectory of critique and commentary.

While the standards of the brass band movement may previously have been judged on the basis of the smattering of ‘great’ composers who had contributed (often rather average) music, we are now judged on the basis of the extraordinary level of musicianship and technique that many of our finest ensembles exhibit.

Modes of expression

New music brings with it new modes of expression, new demands on players, and ultimately new experiences for listeners. Many of us have suffered from this deliberate distancing from that which challenges the status quo.

We can no longer avoid it. We can no longer denigrate it.

Ear and mind

We should no longer tolerate ‘leading’ individuals who themselves find it impossible to understand the aesthetic and historical underpinnings of music as an art form, and the role that the brass band now plays in the exploration of music as an art form and a vehicle for ideas and statements.

Through the brass band, composers can appeal to both our love of a ‘good tune’ and our higher cognitive capabilities.

Music is not just for the ear, but can also be for the mind.

Chris Davies

Chris Davies

Chris Davies graduated from Oxford University with a first-class degree in music before studying tenor horn with Owen Farr at the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama.

He recently studied music psychology and the cognitive neuroscience of music at the University of London, and currently has research interests in advertising psychology.

He is the principal horn at the Tredegar Town Band and winner of the 2010 Rhuband Glas award at the National Eisteddfod of Wales.