With ‘The Lost Circle’ Jan Van der Roost has provided the British Open with a major composition that challenges both preconceptions as well as misconceptions.

Written through the prism of his personal fascination with the prehistoric megalithic structure on Salisbury Plain, it is inspired by man’s millennials-long link to a monument of unresolved mystery.

Doubting, speculating, reappraising

Much like the legions of archaeologists, geologists and anthropologists who continue to reinterpret existing beliefs and certainties when new evidence seemingly arrives beneath their feet, the composer has also returned to his source material (in this case his earlier ‘Stonehenge’ work of 1991) to re-examine its reason for existence; questioning and doubting, speculating and reappraising.

Written through the prism of his personal fascination of the prehistoric megalithic structure on Salisbury Plain, it is inspired by man’s millennials-long link to a monument of unresolved mystery.

Literal or figurative

It ensures that ‘The Lost Circle’ can be seen as either a literal or figurative composition for the brass band medium.

In either case, as a straightforward storyboard work, or equally as an interpretative thesis on cultural significance, it is as beguiling in its actual meaning as Stonehenge itself.

Narrative mode

In narrative mode there are 12 clearly marked stanchion points over the 16 and a half or so minutes - from the opening mystery of ‘Waun Mawn… a long, very long time ago…’, all the way to the final glory of ‘The Lost Circle at its final destination!’.

Taken in figurative context it can be heard in terms of endeavour, perhaps spiritual, reflective of a place of pilgrimage and sacrifice, ritual and worship, or as some academics have suggested, a symbol of early cultural unification.

Most understandably though it tells of the manpowered journey of its dolerite ‘bluestones’ which form the inner circle of the monument.

Then again, and given that the piece was written before the latest ‘findings’ of its huge altar stone potentially originating from Scotland, the aliens could have made it…

Most understandably though it tells of the manpowered journey of its dolerite ‘bluestones’ which form the inner circle of the monument.

Mysterious and magical

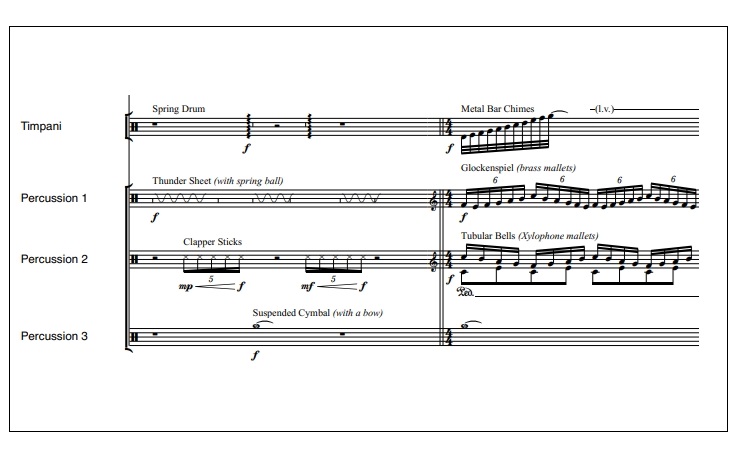

It begins on a boggy peat moor (‘Waun Mawn’) in West Wales (above), at a craggy outcrop on the Preseli Mountains, misty, mysterious and magical (the stones themselves have unusual acoustic properties), hinted at by the wide array of percussion that is used throughout.

The work lasts exactly 365 bars (perhaps a coincidence on the composer’s part given that many believe Stonehenge to be some sort of celestial calendar)

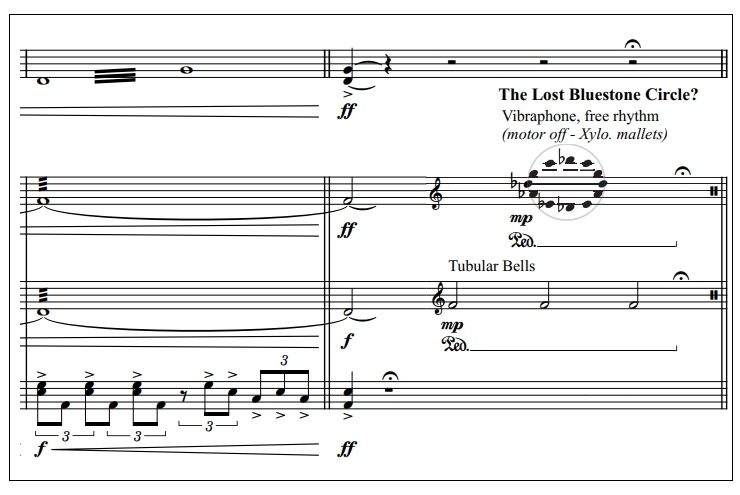

‘The Lost Circle’ is represented in a free form origin motif (a visual key written on the score as a 12-note circular cluster) played on the vibraphone. It heralds a lugubrious lugging of ‘the big boulders’ across the dramatic terrain towards their new home over 170 miles away on Salisbury Plain.

Tricky

The work lasts exactly 365 bars (perhaps a coincidence on the composer’s part given that many believe Stonehenge to be some sort of celestial calendar), with tricky, and at times exceptionally difficult, individual and section contributions – from Stakhanov tubas and troms to multi-dextrous timpani and stratospheric sop.

Hard graft and uneven territory

Along the way it is a journey of hard graft over uneven territory (rhythmically dislocated at times) as well as with elongated interludes of bucolic reflection. There is even a small pastorale section that hints of part being taken over water - reminiscent of a neolithic Ronald Binge ‘Sailing By’.

The texture of the writing is dense and at times seemingly counter intuitive – although deliberately so (the composer has very clear views on his scoring), with some parts positioned in defiance of even modern test-piece norms.

There is even a small pastorale section that hints of part being taken over water - reminiscent of a neolithic Ronald Binge ‘Sailing By’.

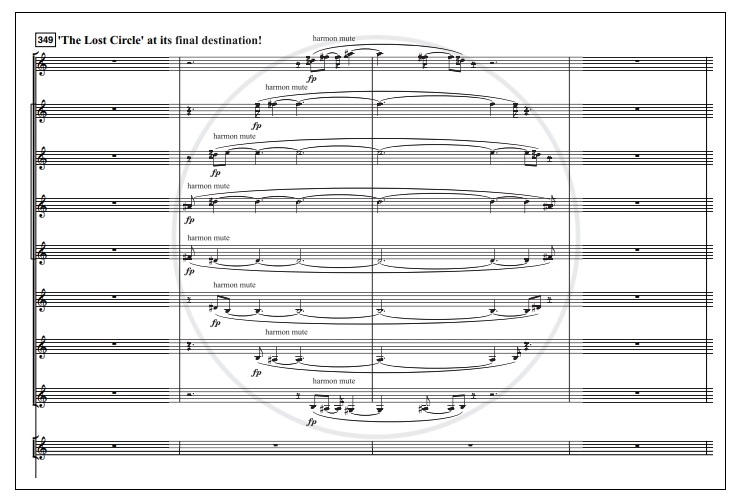

Jan Van der Roost knows what he wants - the use of specific mutes is marked to ensure very prescribed timbre as well as balance (sometimes set against open voices of the same dynamic strength).

Dynamic surprise

It is the dynamic spectrum though that may well surprise the listener (and will test the self-imposed resolve of players bubbling with contest performance adrenaline). It is not a work of huge dynamic extremes and certainly not of incessant loudness.

Flexible seam

Set against the usual ‘blockbuster’ works heard at elite level, the fortissimos are sparingly used and very much the culmination of dynamic progression rather than ‘shock and awe’ tactics. A great deal of the writing is heard within a narrow, but flexible seam of dynamic tonality – in and around forte (sometimes set in or against other sections).

It is interesting that the composer liberally uses ‘singing’ musical terms to indicate the desire to retain a sense of tonal warmth that imbues his rich, oily palette of colour - one that although multi-layered isn’t simply plastered onto the canvas of the score.

the composer liberally uses ‘singing’ musical terms to indicate the desire to retain a sense of tonal warmth that imbues his rich, oily palette of colour - one that although multi-layered isn’t simply plastered onto the canvas of the score.

Keen ears

Undercoats of subtle pigmentation are mixed into the sheen, occasionally breaking through at unexpected moments. Getting those telling textures to find their rightful place in the context of a broad landscape of forte scoring though will take some doing; keen ears are needed to differentiate the horizontal slabs of tinted shading.

MD’s will be wary of the need to keep flow even if a notch or two may be chamfered off in places to gain clarity and processional nobility.

Subtleties too in the pacing of the music – minor calibrations rather than major foot down power drives, although MD’s will be wary of the need to keep flow even if a notch or two may be chamfered off in places to gain clarity and processional nobility.

Triumphant close

By the time we have made it to the final resting place the composer returns once more to his origin source.

This time though the ‘Lost Circle’ motif in the vibraphone is enclosed within a wider circle represented by the eight cornets (above).

It can be seen as representing the inner bluestones within the wider circle of huge sandstone sarsen stones (the percussion cluster seen directly below it in the score). That, like other intriguing aspects of the work is up to the listener to decide - although it does look like Jan Van der Roost has left a coffee cup stain on the score!

A final push brings an absorbing work of curiosities and doubts, contradictions and conjectures to a triumphant close.

Iwan Fox

The Composer:

Jan Van der Roost is a critically acclaimed composer, conductor and educator.

Born in Belgium in 1956, he studied trombone, history of music and musical education at the Lemmensinstituut in Leuven and at the Royal Conservatoires of Ghent and Antwerp. He has taught at the Lemmensinstituut and is special guest professor at the Shobi Institute of Music in Tokyo, Guest Professor at the Nagoya University of Art and Visiting Professor at Senzoku Gakuen in Kawasaki.

He retains a global schedule as a lecturer, clinician and a guest conductor, whilst his extensive catalogue of over 350 works have been performed on over 60 recordings and as part of over 2,000 different artistic projects. His works have encompassed a wide variety of genres and styles, including two oratorios, a symphony and numerous orchestral works, concertos and chamber works.

Jan Van der Roost has composed extensively for the brass band medium – from youth to elite level. His major work, 'Albion' was the test-piece for the 2001 National Championships of Great Britain, whilst ‘From Ancient Times’ was the set-work for the 2009 European Championships.