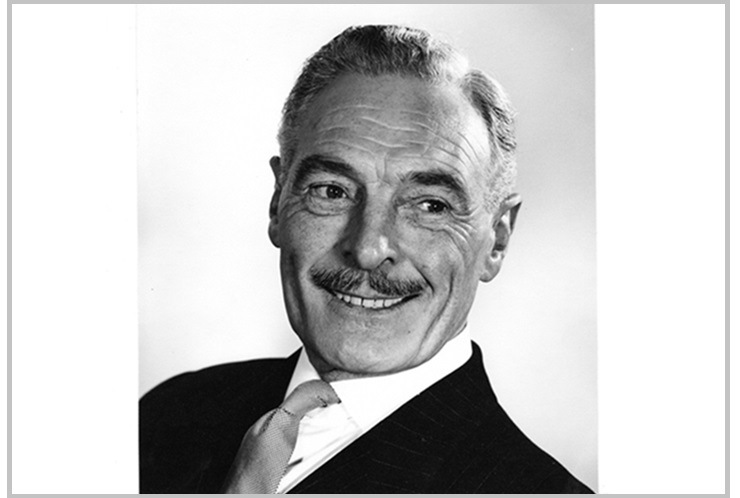

No. 29: Major George H Willcocks MBE, MVO (1899 – 1962)

Few conductors have made such a lasting impression on the banding movement in so limited a period of time as Major George H Willcocks. 60 years and more after his death his name still resonates with almost mythical presence.

From 1956 to 1961 he brought a charismatic brilliance to the stage, winning three National Championships of Great Britain and a British Open title. In total he conducted at just 17 contests, winning nine and only three times coming outside the podium prizes.

However, it was the way in which he directed his bands, and the music he drew from them that mesmerised both players and audiences alike, and was to bring a level of communal admiration that was truly remarkable.

His death, aged 62, robbed banding of one of its greatest conducting talents.

Bandboy Willcocks

George Henry Willcocks was born in Poplar in London on 23rd February 1899, the second of six children to Edwin, a general labourer, and Ada, a housewife, living in Bromley.

Bright, determined, but with limited education opportunities, at 15 he enlisted as Bandboy Willcocks (No. 16621) as a cornet player with the 4th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers.

Bright, determined, but with limited education opportunities, at 15 he enlisted as Bandboy Willcocks (No. 16621) as a cornet player with the 4th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers.

He later transferred to the 1st Battalion, where, as a Private and later Acting Corporal (6448568) he gained his Service Medal. In 1920 was selected for training at Kneller Hall, where he was awarded the ARCM in 1924.

Resourceful ambition

His talent was linked to a resourceful ambition, and in 1926 he became Bandmaster of the 2nd Battalion South Wales Borderers. During the 1930s he bided his time (nepotism was still rife in gaining promotion), married Dorthy Maud Hopkins (1911-1976) in 1930 and had one son, Geoffrey Brian Willcocks (1933-2007).

In 1937 he gained promotion to Bandmaster of the Royal Artillery Band on Salisbury Plain, a year later was appointed Director of Music of the Irish Guards Band, and eventually became Senior Director of Music the Brigade of Guards.

Willcocks directing Fairey at the 1956 National Championships

Ability to inspire

He was reported to have the ability to “inspire” those around him – his friendliness (he was fondly known as ‘Polly’ due to greeting people with an invitation to join him for a cup of tea) allied to a ferocious work ethic and ability to communicate his intentions clearly to those around him.

It however took its toll, and he retired from military service in April 1949 due to poor health – saying to a local newspaper that, “I think I have been very lucky to have lived through the period when soldiering was soldiering.”

He was reported to have the ability to “inspire” those around him – his friendliness (he was fondly known as ‘Polly’ due to greeting people with an invitation to join him for a cup of tea) allied to a ferocious work ethic and ability to communicate his intentions clearly to those around him.

The following month he sailed to start a new family life in Rhodesia, but only stayed three months – his distaste for certain aspects of ‘colonial life’ appalling him.

Ford first

Returning to England he became conductor of the Ford Motor Works Band based at its huge Dagenham site, which he developed to become one of the finest civilian military bands, winning many competitions.

His first involvement in brass bands came in 1952 when he became a vice-president and examiner for the Bandsman’s College of Music. Here he met Harry Mortimer and formed a friendship that eventually saw him persuaded to accept his invitation to conduct the Fairey Band at the 1956 National Finals.

First taste of success: Fairey wins the 1956 National Championship of Great Britain by making musical magic

Personal request

Reluctantly he agreed (only after the Fairey players, who were were so impressed they personally asked him), his stylish baton work and flourishing gestures amplified by a dignified military bearing and suave good looks.

As one player said: “He was a joy to watch and follow, and a joy to be in a band with.”

The Daily Herald newspaper (which sponsored the event) described the win as opening “a new musical world for him”, as “the silver haired major waved his wand and the Fairey men made magic music.”

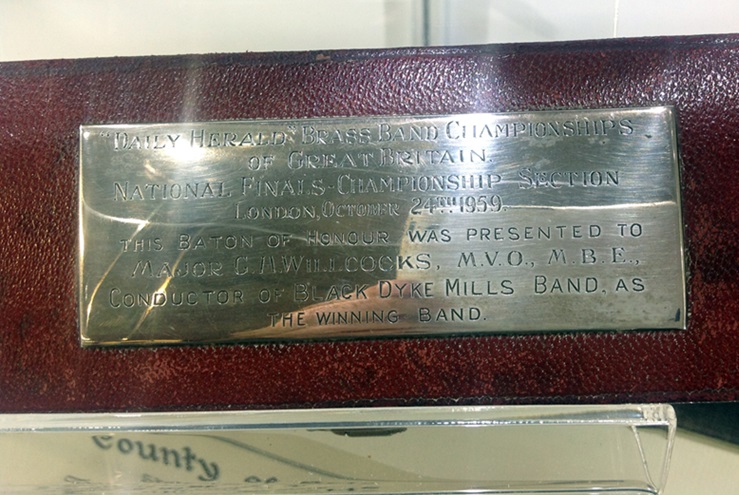

Fairey duly won the National title on ‘Festival Music’ and he became the first man to be presented with the Baton of Honour on his first contest appearance.

Made magic

The Daily Herald newspaper (which sponsored the event) described the win as opening “a new musical world for him”, as “the silver haired major waved his wand and the Fairey men made magic music.”

Writing in the British Bandsman, Eric Ball said that from that moment, “brass band audiences took him to their hearts with something akin to rapture, moved by his picturesque conducting and original approach to the music.”

The Major and his men: Backstage with Black Dyke in 1959

Black Dyke

Others had also noted his success, and with Black Dyke Mills Band looking for a professional conductor, they persuaded him to join them in 1957.

Willcocks was once again reluctant (and had just enjoyed taking Rushden Temperance Band as a well paid one off), but with Maurice Murphy whom he had first met at Fairey Aviation now on principal cornet, he accepted.

His ‘magic’ paid off immediately with victory at the 1957 British Open, with what was recalled as “a beautifully refined” performance of Helen Perkins’ ‘Carnival’ on just four rehearsals.

Most creative

Bram Gay later commented that the work was, “…not enough to stretch the bands that day. But Willcocks, who was one of the most creative conductors imaginable, lifted that funny, ordinary, trite little piece completely out of the rut - a kind of Beecham performance, where you suddenly began to enjoy something that you knew wasn’t really there.”

But Willcocks, who was one of the most creative conductors imaginable, lifted that funny, ordinary, trite little piece completely out of the rut - a kind of Beecham performance, where you suddenly began to enjoy something that you knew wasn’t really there.”

The composer herself was also won over, writing in the British Bandsman that; “The winning band was, of course, superb, and I must congratulate Major Willcocks on a uniquely sensitive and full-blooded reading.”

Rejuvenation

With no National Championship for Black Dyke that year (Willcocks conducted Creswell Colliery) all eyes were focussed on the 1958 Yorkshire Regional Championships.

Victory was secured and hopes were high for the British Open and National Finals, yet Dyke were beaten in both, as an aging band was in desperate need of rejuvenation.

Repeat performance: The smile says it all...

Alchemist's touch

New players came in and with his alchemist’s touch, Willcock’s led them to a second Area title in 1959. With no British Open appearance the focus was on the Royal Albert Hall – the victory on ‘Le Roi d’Ys’ cementing his legend (as well as that of Geoffrey Whitham).

Reflecting on the success, Bandmaster Jack Emmott told the Daily Herald newspaper reporter: “The last few years have seen us in very low water. It was so bad that as recently as last Christmas the band was on the verge of breaking-up.”

Aura

Cornet player Owen Bottomley, who at the time was 57 and had been with the band since 1915, was quoted as saying: "We had a lot of old players and now we have the youngsters and Major Willcocks. They brought us to the top again."

but the Major had an aura of command given to so few. Every man respected him, and he spoke to each player by his first name.

One of them was John Clay, who joined in 1958 aged 14. He later said: “Black Dyke had long been known for being difficult with conductors.

If they were not up to the job, they were politely asked to leave, but the Major had an aura of command given to so few. Every man respected him, and he spoke to each player by his first name.”

1959 Lap of Honour performance

Programme please

One of his favourite stories he told to engage respect was when he conducted the South Wales Borderers' Band at a posh concert in Sussex. As he was walking to the podium, an old lady touched him on the arm and stopping him in his tracks said, "A programme, please…"

Willcocks now inhabited a realm of imperious brilliance that bewitched those who both played under him as well as saw him conduct.

Svengali

A young David James who was a student at the time of the 1959 win was one: “I found myself at the Royal Albert Hall listening to ‘Le Roi d’Ys’ – and it was a truly memorable experience.

The whole performance was beautifully controlled by the Svengali like figure of Major George Willcocks. To me and the audience alike he was mesmerising

Dyke was truly magnificent, and from my seat in the gods they looked like figures from a Lowry painting. The sound that Dyke produced in those days was something very special, and I’ve not heard it since.

The whole performance was beautifully controlled by the Svengali like figure of Major George Willcocks. To me and the audience alike he was mesmerising.”

The Baton of Honour presented to Major Willcocks on his second National victory

Defining performance

Although the band could not retain the title in 1960 (coming third) Willcocks led Black Dyke to a third Yorkshire Area title in 1961 (he also led the Luton Band to Area success in 1959) with the focus of contesting attention once again aimed at the Albert Hall.

Despite the folklore that now surrounds the famous 1959 win, in many ways the 1961 victory on ‘Les Francs Juges’ was his defining performance – the band as one with him in producing a scintillating rendition to beat 26 rivals to the title.

A few days before the band lost a key player through illness, had two more, plus the Major injured in a car crash on their way to London, and to cap it all drew unlucky 13 in the draw.

Shortly after to celebrate the occasion Willcocks travelled to the BBC in Leeds to record a programme with them. It turned out to be their last appearance together. Soon after he had a serious heart attack and died on 12th January 1962.

Death

Shortly after to celebrate the occasion Willcocks travelled to the BBC in Leeds to record a programme with them. It turned out to be their last appearance together. Soon after he had a serious heart attack and died on 12th January 1962.

During his time at Black Dyke Mills Band, Maurice Murphy was principal cornet, with George Willcocks’ son later recalling that; “Dad saw the obvious talent in Maurice. He loved his artistry and wrote a cornet solo for him, initially calling it ‘Maurice Caprice’ in his honour, but on recording it, it was renamed ‘Will o’ th’ Wisp'.”

So different

On other occasions David Willcocks travelled to Queensbury with his father from their Essex home in Upminster: “I must have been about 11. Going there was so different from life in Essex. Rehearsal time was limited as the Saturday morning train from Kings Cross would only get to Leeds or Bradford later that afternoon.

Rehearsals would, I recall, be Sunday mornings/early afternoon before the dash back to the station to get the train back to London. Maurice was a "brisk" car driver as I remember!”

He respected their dedication and commitment to the music and to the task ahead in preparing for the National finals. Dad really took to all this and seemed to get so much out of the band

Connection

What struck him most though was the connection he felt his father had with the people in the band – perhaps a reminder of his youth.

“I remember going to Maurice’s parent's house in Bingley. The atmosphere, the people just walking in through the door, the warm coal fire, the accents, and friendliness towards Dad.

He respected their dedication and commitment to the music and to the task ahead in preparing for the National finals. Dad really took to all this and seemed to get so much out of the band.”

The great man at work with Black Dyke in an open rehearsal

Legacy

In response, the great Jack Emmott perhaps summed him up best.

“Was he a showman? I would definitely say not. A messiah? This would be nearer the truth.

Whatever the public saw him do on a contest platform was the same demonstration of enthusiastic energy as took place in the practice room. Every gesture had a meaning understood by the men under him, and which instilled confidence.

He was a man of sound principles. No one was beneath him, he would listen to comments about a test piece from anyone in the band or even Pondashers sat listening, even though he had made his mind up. At Black Dyke he was one of the lads.

He was a man of sound principles. No one was beneath him, he would listen to comments about a test piece from anyone in the band or even Pondashers sat listening, even though he had made his mind up. At Black Dyke he was one of the lads.”

Such was the affection that Willcocks wrote several compositions, the most well-known being his marches ‘The Champions’ and ‘The Pondashers’ – dedicated to the band and the people who he so admired and so admired him back in return.

His picture now hangs on the Black Dyke bandroom wall – the man and the myth he created forever in its rightful place.

Tim Mutum

(The author wishes to thank John Clay for his help and with the provision of images for the article)

4BR Hall of Fame: No.1: Jack Atherton

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2019/1832.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.2: Albert Baile

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2019/1836.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.3: Stanley Boddington

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2019/1842.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.4: Bram Gay

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1848.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.5: Leonard Lamb

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1855.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.6: Arthur Stender

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1866.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.7: Violet Brand

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1871.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.8: Eric Bravington

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1875.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.9: Norman Ashcroft

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1879.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.10: Albert Chappell

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1884.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.11: Betty Anderson

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1889.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.12: Trevor Walmsley DFC

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1897.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.13: Percy Code

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1903.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.14: George Thompson MBE

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1909.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.15: Willie Lang

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1914.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.16: James Scott

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2021/1916.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.17: Jack Mackintosh

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2021/1922.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.18: Teddy Gray

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2021/1928.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.19: Rowland Jones

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2021/1932.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.20: Helen Perkin

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2021/1944.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.21: Lt Col Cecil H Jaeger OBE

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2021/1954.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.22: Alex Mortimer

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2021/1966.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.23: Henry Geehl

https://4barsrest.com/articles/2022/1987.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.24: Geoffrey Brand

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2023/1996.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.25: Maurice Murphy

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2023/2002.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.26: Arthur Butterworth

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2023/2011.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.27: Gordon Langford

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2023/2015.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.28: Frank Wright MBE

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2023/2040.asp