Whilst it is the crash, bang, wallop of modern day test-piece finales that tend to get contest audiences drooling like a pack of Pavlov’s dogs eyeing up a juicy bone, it has always been the beauty of a ‘middle’ section of reflection that instils a true heartfelt appreciation of what a brass band can do best.

Inspiration

There have been many fine examples of the genre - some inspired by nature, others by more aesthetic reflections, many by personal loss, others by feelings of belief, superstition or mystery.

Whatever the root DNA, these are our five that stand out for us. They are in chronological order.

1. ‘Elegy’ from ‘An Epic Symphony’

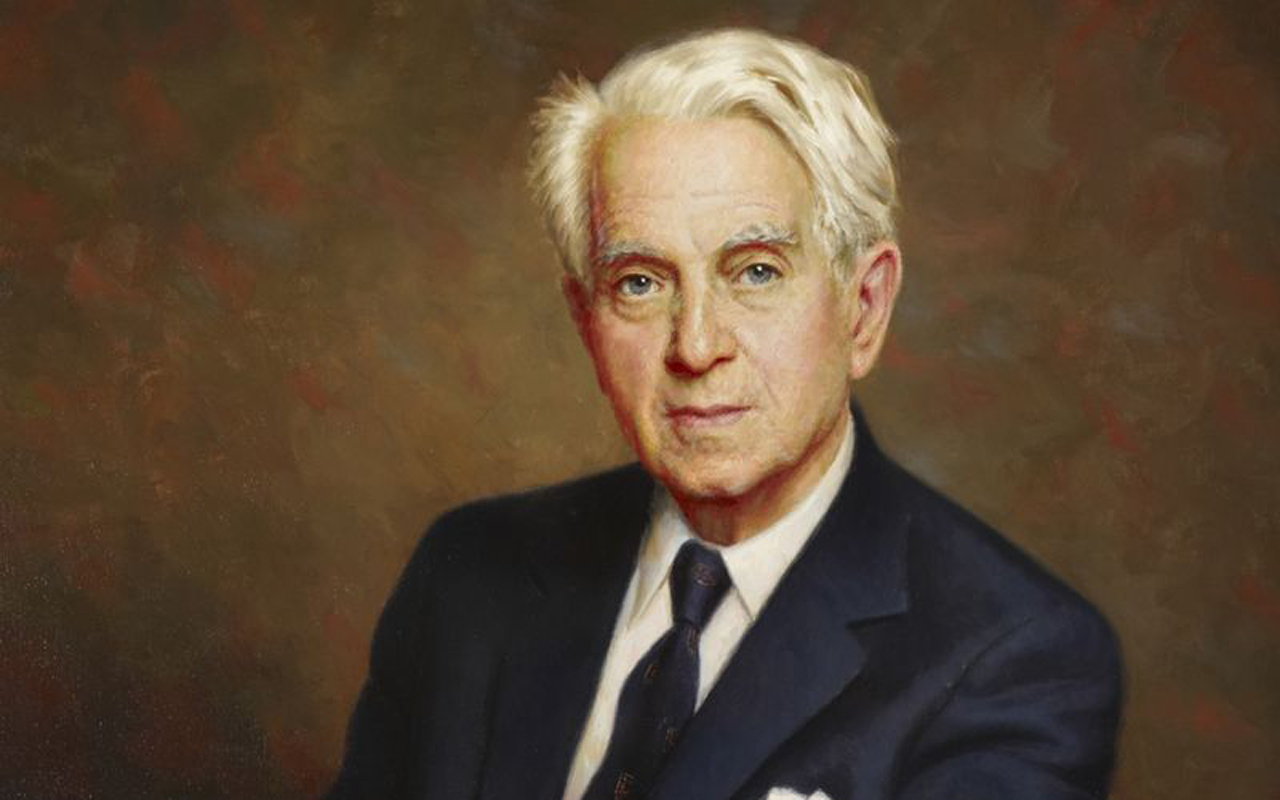

Percy Fletcher (1879-1932)

First contest performance: 1926 National Championships of Great Britain

Although Percy Fletcher did not experience the horrors of First World War trench warfare, he would have certainly observed its effects on the troops that would have packed into His Majesty’s Theatre in London where he worked as Musical Director from 1915.

His was a compositional pen filled with the ink of empire: ballads, musicals, romances, serenades, waltzes and sketches. He mimicked Elgar and had a mastery of pastiche, yet ‘Epic Symphony’ and especially its central ‘Elegy’ speaks of a composer with a much deeper emotional hinterland.

It is a memorial to those who never enjoyed a return to the theatrics of Drury Lane - the muffled tread of mudded boots underpinning the haunting lyrical impressions that were at the time unspoken off, but by 1926 were already expressed in the art of Christopher Nevison, John Nash, Colin Gill and John Slinger-Sargent and the poetry of Sassoon, Blunden, Brooke and Owen.

Industrial loss

Between the optimism of the opening ‘Recitare’ and the bluff pomp of the ‘Heroic March’, the ‘Elegy’ is a sombre evocation of the horrors of the industrial loss of life on the muddy fields of the Somme and Passchendaele.

It is a memorial to those who never enjoyed a return to the theatrics of Drury Lane - the muffled tread of mudded boots underpinning the haunting lyrical impressions that were at the time unspoken off, but by 1926 were already expressed in the art of Christopher Nevison, John Nash, Colin Gill and John Slinger-Sargent (above) and the poetry of Sassoon, Blunden, Brooke and Owen.

There is a chilling beauty to it.

The arabesques of the solo cornet and soprano float gently above like the early biplanes in the sky, whilst below there is nothing but death - the air of sadness only partially lifted by the euphonium, before the whole band delivers a response of heart-felt emotion.

2. ‘Nocturne’ from ‘A Moorside Suite’

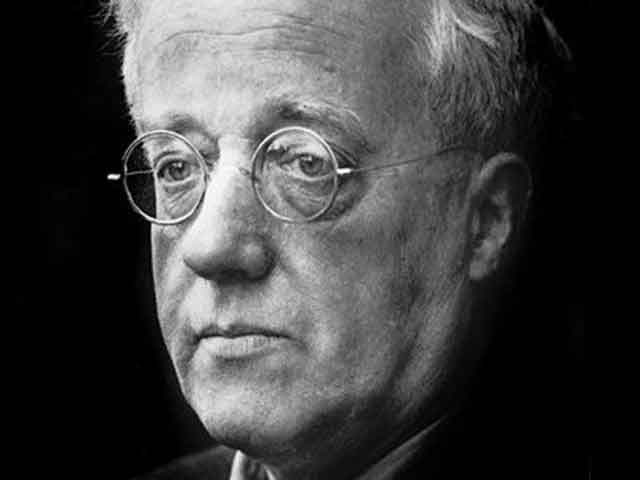

Gustav Holst (1874 - 1935)

First contest performance: 1928 National Championships of Great Britain

There is also a beautiful fragility to Holst’s ‘Nocturne’.

It is the heartfelt core of a work that speaks deeply of his appreciation that the late Victorian drive to become the global industrial powerhouse of the age had come at a terrible price for the bucolic land from which he sought personal as well as musical inspiration during his youth.

Locust years

Like ‘Epic Symphony’, ‘A Moorside Suite’ opens with optimism - this time with a bright ‘Scherzo’.

It closes with a ‘March’ of lightweight hopefulness still evident in the last years of the 1920’s, but which was soon to be replaced by the harsher, darker realities of what Winston Churchill was to call the ‘locust years’ of the 1930’s.

The ‘Nocturne’ bridges that gap of personal emotion; deceptively simple yet yearning treacherously in its lyrical breadth and dynamic subtlety - a potent of things to come.

It closes with a ‘March’ of lightweight hopefulness still evident in the last years of the 1920’s, but which was soon to be replaced by the harsher, darker realities of what Winston Churchill was to call the ‘locust years’ of the 1930’s.

The cornet is the lead figure plotting a moonlight course through the darkened night. He is joined by fellow ensemble travellers, at times isolated themselves, as the music builds to a shadowy climax resonating with a low brass foundation of liquid gold.

The final chord hints at the breaking dawn sunlight.

The ‘Nocturne’ was later arranged for string orchestra, but in its brass band form it retains the purity of its genius.

3. ‘Cortege’ from ‘Pageantry’

Herbert Howells (1892 - 1983)

First contest performance: 1934 National Championships of Great Britain

There is little doubt that ‘Pageantry’ remains one of the finest works ever written for the brass band medium.

Not a single note is misplaced, nor a single phrase burdened with needless insincerity.

It has a forensic construction, yet it remains an unashamedly romanticised interpretation of a medieval England that was being played out on the screens of ODEON cinemas the length of breadth of 1930’s Britain with Basil Rathbone and Errol Flynn as its leading men.

It is a score that could have been used for an Alexander Korda film (Holst certainly wrote one) - the type written by Miklos Rozsa or Erich Korngold.

The brilliant fanfare opening to ‘King’s Herald’ and the throwing down of a musical gauntlet by the principal cornet in ‘Jousts’ could have accompanied Captain Blood or Robin Hood.

It is a score that could have been used for an Alexander Korda film (Holst certainly wrote one) - the type written by Miklos Rozsa or Erich Korngold.

Highest peaks

However, it is the solemn ‘Cortege’ that raises the music to the highest peaks of inspiration - opening with two processional baritones as funeral pallbearers, the cornet leading like a soulful widow in their wake.

Howells was a sensitive man who felt loss grievously (the death of his young son cast a life long shadow), and in 1934 the British musical world lost Holst, Delius and Elgar – the latter very much a mentor.

The music certainly flows like a Royal cortege of old – reaching its glorious climax as the coffin is drawn past, magnificent in its sad, stately progress.

It closes as it began, the sound dying to its embers, the soprano a lone voice, the horn leading the repose.

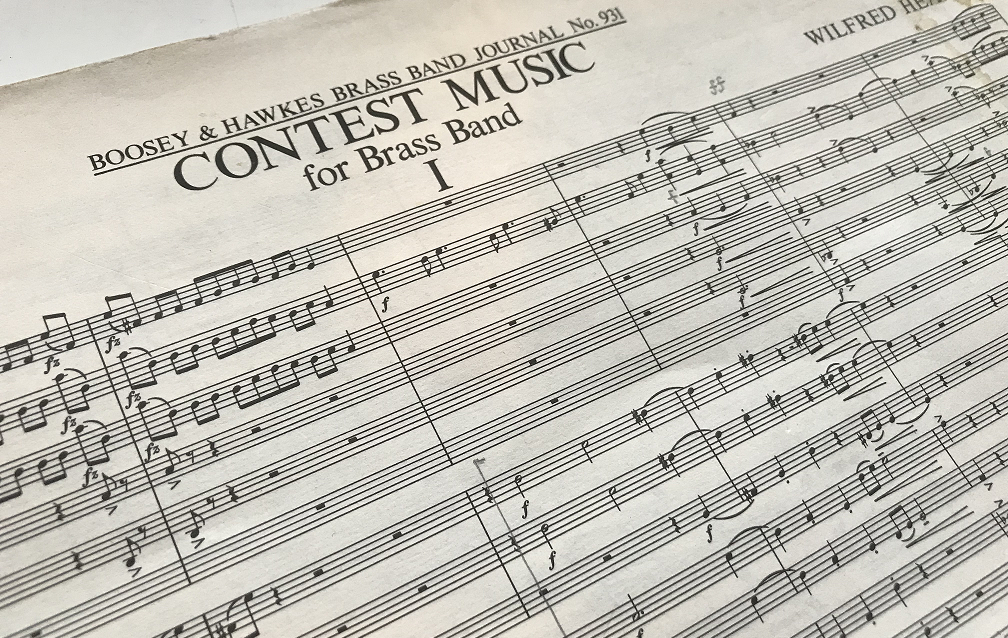

4. Movement II ‘Molto Adagio’ from ‘Contest Music’

Wilfred Heaton (1918 – 2000)

First contest performance: 1978 European Brass Band Championships

There is nothing remotely romantic about Wilfred Heaton’s masterful ‘Contest Music’.

Originally commissioned for the 1973 National Championships of Great Britain it was deemed unsuitable and not used until 1982. Even then it was still years ahead of its time.

It is almost a philosophical work of exploration (reflecting Heaton’s own searching intellect) - the three movements echoing classical proportions based on material sketched many years before.

The angular drive of the opening and the glorious development of the third movement sandwich what seems at first to be a rather ambiguous central section.

It is almost a philosophical work of exploration (reflecting Heaton’s own searching intellect) - the three movements echoing classical proportions based on material sketched many years before.

Cast iron

However, it is in fact cast iron certainty; the core elements exposed like the girders of the Forth Bridge; engineered for purpose, the by-product an austere beauty (marked con espressione) created by form, function and more important than anything else - space.

The sparseness of the scoring places huge demands on the players (cornets especially), the pulse constant in its subtle calibration, starkly passionless yet deeply emotive. It is hard to think of another brass band work which encompasses so much in so little.

The high C# pause of the solo cornet is followed by a depressive fall that is almost shattering in its expectations, yet because of that the aesthetic continues to draw you in as the cornet line follows its descent to nothingness.

5. ‘In Memoriam’ from ‘Royal Parks’

George Lloyd (1913 - 1998)

First contest performance: 1985 European Brass Band Championships

George Lloyd’s complex life was blighted by cruel circumstance.

It combined emotional highs and lows; compositional recognition and critical acclaim bookending years of isolation and at times, overt ignorance of his musical output.

A traumatic naval war time experience scarred him emotionally, and it was the love of his wife that gradually brought him back to writing after a 20-year break. Then, although the BBC played his works (especially his 8th Symphony) his compositional voice was at odds with the ‘progressive’ outlook favoured by those in charge of regular commissions.

Cruel circumstance

Late in his life Boosey & Hawkes asked him to write the set-work for the 1985 European Championships (although no fan of contesting). The three-movement work sought inspiration from the Royal Parks and their connection to the people of London.

‘Dawn Flight’ recalled the early morning sound of geese flying over his flat, the finale, the joyful sounds of families enjoying a sunny ‘Holidays’ weekend.

It brought back terrible memories, but also a desire to memorialise a tragedy that he said in modern day life “was forgotten so quickly”.

Cruel circumstance however brought a visceral intensity to the central ‘In Memoriam’.

The composer’s home was just a few hundred yards from the Regent’s Park bandstand. On the 20th July 1982 he witnessed the aftermath of the IRA bomb that killed seven bandsmen of the Band of the Royal Green Jackets and 24 members of the audience.

It brought back terrible memories, but also a desire to memorialise a tragedy that he said in modern day life “was forgotten so quickly”.

He knows

Simple thematic material is repeated towards the most telling ‘emphatic’ climax – one underpinned by the sound of muffled funeral drums. The music returns to whence it came, closing with a tender Amen cadence.

Such was its personal intensity that following a concert where it was performed Lloyd was approached by a psychiatrist, who said that he had been treating a severely depressed woman.

He told him that she would not communicate, and so the psychiatrist tried music, and in particular ‘In Memoriam’. Amazingly, she began to weep and then speak for the first time in months.

Her first words were: "He knows.”