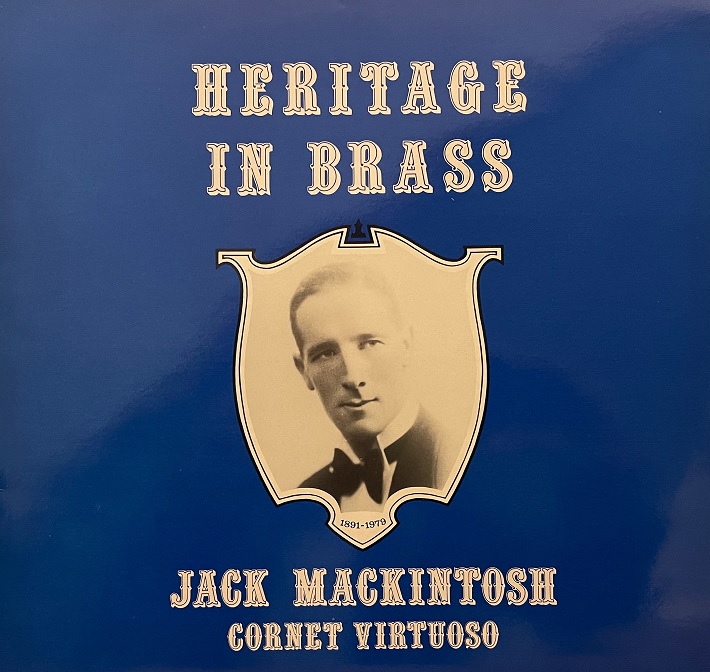

17: Jack Mackintosh (1891 – 1979)

In the interwar years English cricket was blessed with a pair of batsmen that formed arguably the greatest opening partnership in the history of the game – Jack Hobbs and Herbert Sutcliffe.

Hobbs was ‘The Master’; small, agile and dynamic, blessed with the footwork of a ballet dancer and the eye of crack sniper. Sutcliffe was his complete opposite; statuesque, determined and proficient, hewn from Yorkshire limestone with a temperament to match.

Opposite sides

At roughly the same time English banding was also blessed with two cornet players cast from opposite sides of a musical mould: Harry Mortimer and Jack Mackintosh.

Mortimer was the eloquent artist – the delicacy of his playing leaving only an imprint of beauty on the mind. In contrast, Mackintosh was the brilliant engineer - his stamp of quality forged by the audacity of his technique.

The comparisons were fascinating, although the one without the other was like watching Hobbs or Sutcliffe compile a century after the other had been dismissed with the first ball of a test match.

Listening to them perform however brought greater understanding of their very particular genius - their musical influence lasting well beyond their peak years of competitive activity.

Jack Mackintosh joined Harton Colliery Band in 1919

Jack Mackintosh was born in Sunderland in 1891 (Mortimer was 10 years younger). The eldest of eight children he later told Bram Gay that his father had “just left a cornet knocking around the house, in case anybody wanted to play.”

Jack did - and with this father’s encouragement and by listening to Edison recordings he soon became proficient enough to play with the Sunderland East End Prize Band.

Childhood rheumatic fever nearly cost him his life, the effects disjointing his fingers so that his grip became unorthodox (he used a rubber band between his fingers to keep them apart).

Perfect apprenticeship

However, his determination to improve through hard work and practice was embed into his personality and he left school to play with a small ensemble providing the musical accompaniment to silent films at the Sunderland Palace Theatre. In 1909 he was earning 35 shillings a week.

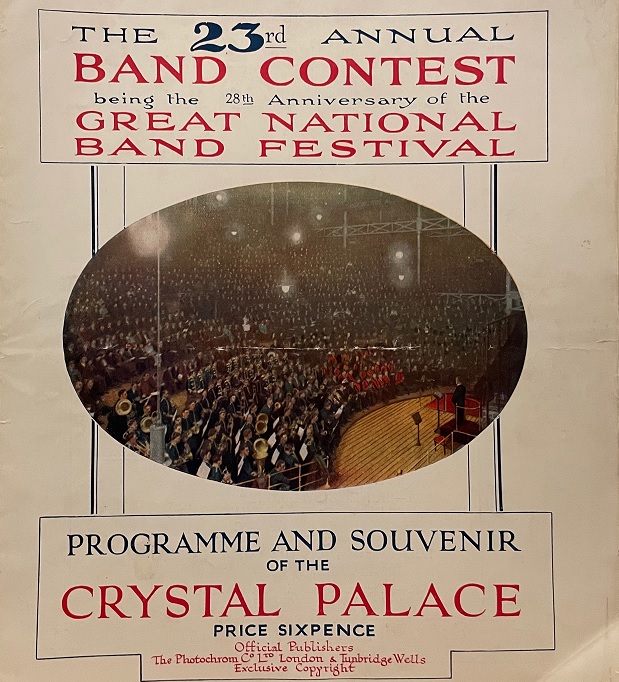

His talent was soon spotted, and he was approached by the secretary of Hetton Silver Band who asked him to play at the 1912 Grand Shield contest at Crystal Palace - just a week later.

It was the perfect apprenticeship. “It was a marvellous job,” he later said. “You couldn’t wish for anything better for practice and experience. Band of five, that’s all - piano, violin, cornet, double bass and drums.”

His talent was soon spotted, and he was approached by the secretary of Hetton Silver Band who asked him to play at the 1912 Grand Shield contest at Crystal Palace - just a week later.

Even though he only attended one rehearsal the result was a victory.

St Hilda

He later recalled: “7.30am at the Goat & Compasses at Kings Cross, practicing arias from Donizetti’s ‘Emilia’. It was a nice selection, nice cornet solo in it. It was the biggest surprise of my life when we won and St Hilda winning the top section too.”

His fleeting appearance hadn’t gone unnoticed and shortly after returning home he was invited to join St Hilda Colliery Band on a professional basis as support to Arthur Laycock.

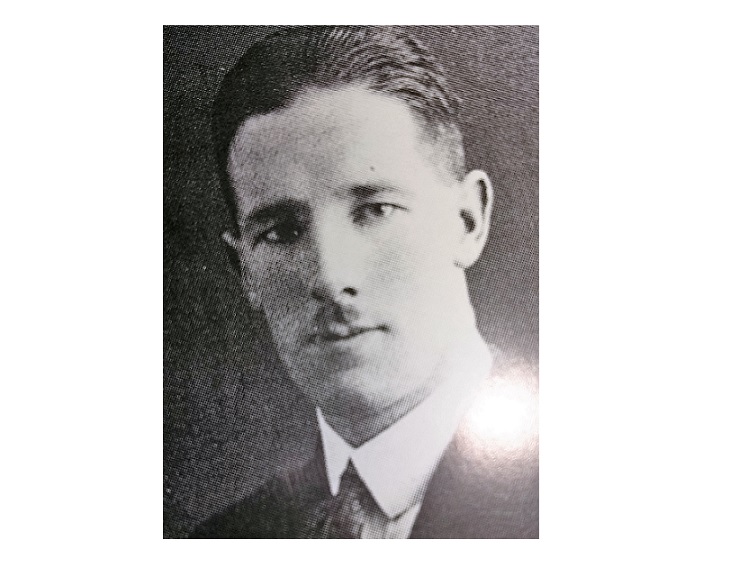

The young tyro...

He carried on playing at the Sunderland Palace but when Laycock was called up for military service in 1916, Jack became principal cornet, holding the position until 1919, under the likes of William Halliwell who he described as ‘a great band trainer’ rather than a creative musician. Mackintosh provided him with the missing artistry.

The years providing the musical backdrop to silent films had given Jack remarkable stamina to compliment his technical brilliance and artistic assuredness. It also enabled him to move seamlessly into the banding world with a confidence that brokered no argument.

Showmanship

At times it bordered on insoucianct showmanship (cadenzas played with one hand behind his back), but he knew he had to make an impression - which he did, especially with the solos of American cornet star Herbert L Clarke.

As he recalled: “I learned to memorise my solos, stand up and really play to the audience. They liked it. I used to put a lot of arpeggios in you know. My cadenzas were called ‘the bucking broncos’ by the band”. The lip trills and flexibilities were imitations of what he heard listening to the Mendelssohn ‘Violin Concerto’.

For a retainer of £100 a year I was to attend at least once a week, guarantee all contests, and they would pay me for engagements as they came along. Financially I was doing quite well.”

At Belle Vue in 1919 Harton Colliery took the title, beating Black Dyke and St Hilda Colliery who ended third.

Jack’s disappointment was tempered though by a visit almost as soon as he got home through his front door.

“They were there on the doorstep asking me to join Harton. We came to an agreement. For a retainer of £100 a year I was to attend at least once a week, guarantee all contests, and they would pay me for engagements as they came along. Financially I was doing quite well.”

He stayed 11 years and was billed on concert programmes as the ‘Prince of Soloists’ and a ‘living legend’.

Totally different

Although in private a studious, unassuming man, his playing persona was totally different.

As a result, the band, one that surreptitiously existed as a blend of ‘amateur’ and ‘retained professional’ players, became a consistent contesting force. Although they never added another major title they claimed podium finishes at both the British Open and National Championship.

It was at this time, Jack Mackintosh’s profile started to mirror that of Harry Mortimer - thanks in no small part to a stroke of luck.

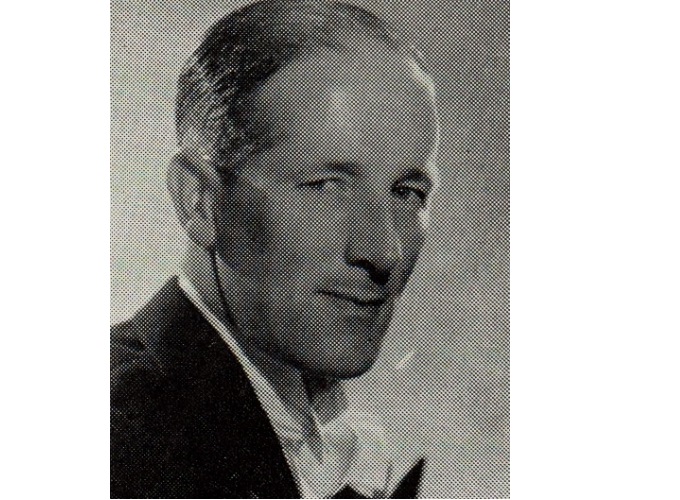

Mac and Mort: The two greatest corent players of the age

Alpine Echoes

In 1928 Harton was asked by HMV Records to record the National test-piece, ‘A Moorside Suite’. As it took up three sides of the old 78s, one needed to be filled, and as Jack had been featured at the Crystal Palace event as a soloist, he was asked to perform Basil Windsor’s ‘Alpine Echoes’.

It had never been played in public before and with Jack’s assistant, Harry Smith, climbing behind the great organ to play the echo effect, it brought the house down.

The record sold in its thousands; local sales helped no doubt by a report in the South Shields Gazette that said that Jack had, “… aroused intense enthusiasm by his wonderful interpretation. He repeated it, as an encore, introducing his own conception, obligato, cadenza and technical movements.

It had never been played in public before and with Jack’s assistant, Harry Smith, climbing behind the great organ to play the echo effect, it brought the house down.

The ovation that followed left the artist no alternative to a third encore and he played ‘Facilita’ with the skill and artistry of a ‘wizard of the cornet’, as an expert loudly proclaimed him from the body of the hall. Fifty thousand people listened to his music and fifty thousand people rose to their feet and cheered him.

None were more enthusiastic than the soloists of competing bands, one after another rushing forward to give his effusive congratulations.”

His performance at Crystal Palace in 1928 was hailed by the public

Giveaway really

Jack was now a star and was offered a contract to record twelve solos a year for three years.

“I thought it was a marvellous offer,” he said. “If I’d have known then what I know now I’d have got better terms. It was a giveaway really. But in those days we thought it was wonderful just to get on record.”

These recordings were made with a military band accompaniment but were not without controversy.

However, the professional players of the Columbia Studio Military Band were not impressed - although not by his artistry. Paid by the hour, his brilliance had cost them a full days’ work, with Jack telling them that he wanted time for a quick look at London before going home the same night.

At his first session in April 1929, he arrived from Newcastle at six in the morning and recorded ‘Facilita’, ‘Silver Showers’, ‘Carnival of Venice’ and ‘Zelda’, all before lunch – and all in ‘one take’ from memory direct onto the wax master.

However, the professional players of the Columbia Studio Military Band were not impressed - although not by his artistry. Paid by the hour, his brilliance had cost them a full days’ work, with Jack telling them that he wanted time for a quick look at London before going home the same night.

Included in the eventual 37 recordings made were ones with Harry Mortimer such as ‘Mac & Mort’, ‘Tom & Kitty’ and ‘Jack & Jill’.

There soon emerged a mutual, if not over-endowed respect. “…he had a sweet tone and a good range,” Jack said of Harry. In return Harry described him, “as possibly the best trumpet player of them all.”

Stark difference

The stark difference in playing styles made true comparison redundant, as Bill Skelton, a celebrated horn player with Callenders and Ferodo Works Band later told journalist and author Arthur Taylor.

“To my mind there was no real comparison… Harry could get more music from a single crotchet than anyone I’ve ever heard – he could strike a note so beautifully it would make you cry. He was very clever at choosing music that he could cope with.

Jack played music that Harry couldn’t aim at. As a musician he started where Harry left off. But Jack’s tone was hard - no soul, you know.”

The separation in style was further emphasised in 1930 when Jack took the decision to take up the offer to become a founder member of the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Sir Thomas Beecham.

Bowing out with a flourish at Eastbourne

Fifteen pounds a week

Aged almost 40 he knew he had to secure his future. Playing in brass bands actually offered him around the same wage packet, but the world was changing; theatre work had diminished, jobs with the local orchestras such as the North East Coast Symphony Orchestra and Newcastle Bach Choir was intermittent, and ‘works’ bands were changing too - 1930s colliery employment wasn’t as secure as it had once been.

“Financially there was nothing much in it,” he later recalled. “Fifteen pounds a week. A lot of money in 1930, but not much better than I already had, one way or another.”

The timing was unfortunate for the band and some players resented his decision - including conductor Ernie Thorpe.

“Financially there was nothing much in it,” he later recalled. “Fifteen pounds a week. A lot of money in 1930, but not much better than I already had, one way or another.”

His last week with Harton in Eastbourne, where the council prepared special posters for his farewell performance, was marked by some rancour - stoked in part by Jack himself.

On your way

On the Saturday he played his solos with added spontaneous showmanship. The audience were thrilled, although an exasperated Ernie Thorpe finally blew a fuse, threw away his baton and shouted at him “Right, go your own b….y way, Jack!”

He did – although not before he everyone to the pub at the interval and bought them all a drink. On seeing him step off the band bus for a last time, the band secretary Jack Trelease remarked: “There goes the world’s greatest cornet player.”

Jack spent 21 years at the BBC Symphony Orchestra

Jack Mackintosh stayed at the BBC for 21 years, leaving in 1952 when he was replaced by his son, Ian.

It may have been a different discipline, yet Jack’s innate confidence and showmanship was retained to the end.

“They found me a bit too free at times,” he recalled. “When I had a solo I liked to make a lot of it.

Ernest Hall and Eric Pritchard were the exact opposite - steeped in the symphony business and very correct. Ernest was a great player. We had a marvellous time together. I think I fitted in you know. Anyway, I stayed twenty - one years. In a way I felt buried. The BBC was very strict in those days and wouldn’t let us play anywhere else.”

Musical legacy

He then joined the Philharmonia until 1970, and played under Weingartner, Sir Henry Wood, Toscanini, Karajan and Barbirolli and toured extensively including Europe and South America.

If his musical legacy as a player was marked, it was indelibly stamped by his years (1934 until 1976) as Professor of Cornet at the Royal Military School of Music, Kneller Hall.

If his musical legacy as a player was marked, it was indelibly stamped by his years (1934 until 1976) as Professor of Cornet at the Royal Military School of Music, Kneller Hall.

Hundreds of players benefitted from his teaching and insight - generations moulded with a level of musicianship based on disciplined craft and practice.

Thankfully, his talent was not lost to the banding world, and he later became a highly respected adjudicator, taking to the box at the National Finals and the British Open.

Still on record...

Public and private

The public persona of Jack Mackintosh was very different to his private one.

The flamboyant character, a soloist ‘playing to the gallery’ with devilish disregard for convention was at odds with the man who enjoyed family life, was a keen Sunderland FC supporter and had a fascination for cars.

Following his death aged 88 in Epsom Hospital on 3rd November 1979, the tributes were heartfelt and generous.

“He was not only a great artist and showman, he was a thorough gentleman and a good sport. That is why we loved him.”

Harry Mortimer said, “…his name will remain part of brass playing for a long time to come”, whilst Bernard Brown, the celebrated Professor of Trumpet at Guildhall School of Music added: “You knew you couldn’t match his technique when you sat next to him, but in the nicest possible way he made you feel that one day you might!”

Gentleman

A fellow bandsman from his Harton Colliery days, Harry Smith, wrote “He was not only a great artist and showman, he was a thorough gentleman and a good sport. That is why we loved him.”

However, it was his daughter Sheila who understandably captured the very essence of Jack Mackintosh the man.

“He was just the loveliest of fathers, a great family man and his family always came first. He overcame such a lot in his youth to become a success, and he was greatly admired.

He was a very upright man, a real gentleman in every way. He was also a very kind man and a lovely person."

Tim Mutum

4BR Hall of Fame: No.1: Jack Atherton

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2019/1832.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.2: Albert Baile

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2019/1836.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.3: Stanley Boddington

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2019/1842.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.4: Bram Gay

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1848.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.5: Leonard Lamb

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1855.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.6: Arthur Stender

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1866.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.7: Violet Brand

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1871.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.8: Eric Bravington

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1875.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.9: Norman Ashcroft

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1879.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.10: Albert Chappell

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1884.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.11: Betty Anderson

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1889.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.12: Trevor Walmsley DFC

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1897.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.13: Percy Code

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1903.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.14: George Thompson MBE

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1909.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.15: Willie Lang

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1914.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.16: James Scott

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2021/1916.asp