15. Willie Lang (1919 – 2006)

During the Second World War, Willie Lang was a tank commander in the 1st Field Squadron Royal Engineers of the 8th Army.

He served in conflicts in North Africa, Italy and Austria - putting the ‘pressure’, as he later called it, in playing for Black Dyke Mills Band and the London Symphony Orchestra into a perspective people understood fully when he regaled them accompanied by a post-performance drink.

Funny business

Wille enjoyed being a storyteller, and although in later years the tales became ever more colourful and humorous, at heart they were also poignant and telling.

He later said that warfare was, “a funny business – rather like being in symphony orchestra, you know. Most of the time you’re bored to tears but occasionally you’re frightened to death.”

There is little doubt his was a remarkable life.

He later said that warfare was, “a funny business – rather like being in symphony orchestra, you know. Most of the time you’re bored to tears but occasionally you’re frightened to death.”

The young maestro (left)

Born in Norland in West Yorkshire of Irish parents, he became interested in the local brass band which rehearsed in a hut in a disused quarry near his home.

After rudimentary lessons from his father he was given a cornet by the conductor, George Ramsden at the age of 10. He later recalled how the kindness of others meant a great deal to him, although circumstance also gave him a steely edge of determination following the death of his father when he was aged 11.

He later recalled how the kindness of others meant a great deal to him, although circumstance also gave him a steely edge of determination following the death of his father when he was aged 11.

Talent spotted

Willie went to live with his aunt and brass banding soon became more than a hobby as he tasted the heady atmosphere of the Crystal Place in 1932, playing ‘A Downland Suite’ with Bradford City Band.

His talented was soon spotted and Black Dyke principal cornet Harold Jackson, whom he had known since he was a youngster, wanted Willie as his assistant.

Norland Band (Willie Lang sat on the grass)

Queensbury experience

His audition, aged just 16, was made up of sight-reading and solos – his confidence in the former based on the hours of practice he undertook each day at home on the very Alex Owen and John Gladney arrangements he played: “It was lonely up there and it was raining nearly all the time, so that was the only thing I could do.”

He soaked up the Queensbury experience.

“Harold Jackson used to keep me behind after band practice and go through exercises with me,” he said. “He taught me what I couldn’t do and that showed me what I had to do to get over things. I learned a lot from him and from Owen Bottomley, who was a great stylist on the cornet.”

“I think that settled me down,” he said. “I didn’t like to let myself down, or the band, so I took it very seriously and got down to work.”

Willie’s first stint at Dyke was short lived, as a boyish prank led to his departure and a spell at Hebden Bridge, but a year later Jackson left and he was offered the top cornet role at short notice and found himself leading the band at the 1938 National Championships.

“I think that settled me down,” he said. “I didn’t like to let myself down, or the band, so I took it very seriously and got down to work.”

Ready for action with Ferodo Works Band

Stonemason

However, unwilling to be tied to John Foster Mills as an employee, Willie trained as a master stonemason in nearby Sowerby Bridge – his work still seen on local buildings such as the local Barclays Bank to this day.

He was proud of his talents as both as a musician and craftsman, and with his employer being a former player under Fred Mortimer he was given time off to play with the band to ensure he excelled at both.

He quickly became one of the most celebrated cornet players of the era – although one cut short by the advent of the Second World War.

Tank commander

Keen to ‘play his part’ as he said, in 1941 Willie Lang was conscripted - initially joining the Artillery but later being transferred to the Royal Engineers and becoming a tank commander.

Like one of his heroes, the great John Paley, he took an old instrument to practice in the open air, whilst he later recalled that on one occasion, he whistled the last movement of ‘Kenilworth’ on his way into battle.

Like one of his heroes, the great John Paley, he took an old instrument to practice in the open air, whilst he later recalled that on one occasion, he whistled the last movement of ‘Kenilworth’ on his way into battle.

National hat-trick champions

Making of the man

War both marked him and made him as a man.

It was clear on his return to Black Dyke in 1946 when asked to do, “another damned audition”. He told the legendary A O Pearce; “I’m not going to stand in a draughty passage while the band decides what I’m going to get.”

Not prepared to play for a year to gain a discretionary retainer, he stood firm. Accepted back in his former role, £50 became £100 a year, then with the arrival of Harry Mortimer, £500.

Not prepared to play for a year to gain a discretionary retainer, he stood firm. Accepted back in his former role, £50 became £100 a year, then with the arrival of Harry Mortimer, £500.

He knew his value - something that irked him during the War when he was told that a recording he made for HMV of ‘Bless this House’ had sold 2 million copies. When he asked if he was to receive anything from its popularity, the answer was no, although they felt he would been pleased to be informed.

Not so. The person on the other end of the phone was given short shrift.

Tough

Harry Mortimer called him “tough”. And there was no doubt about that.

No shrinking violet, he was once deputised to sack Joe Wood, the popular but rather inept Black Dyke Bandmaster.

It was done with bluntness after a concert. “Joe, you’re a nice fellow, but you’re no bloody use as a conductor and you’re sacked.”

It was done with bluntness after a concert. “Joe, you’re a nice fellow, but you’re no bloody use as a conductor and you’re sacked.”

With Willie as the cornerstone, Black Dyke enjoyed a fine period of post war success. A hat-trick of National titles was secured, and he became the 1947 All England Solo Champion.

He was also a member of the quartet which won the Oxford National Championship in 1947/48/49.

National quartet champion

In December 1950 he left Queensbury to join the West Riding Orchestra, although he also played for Brighouse & Rastrick for several months. He returned for a third time in 1952, staying until 1954 when he departed for good.

He never quite got on as well with Alex Mortimer as he did with Harry, and for a while he enjoyed a lucrative freelance career with the likes of Ferodo Works, although he still worked as a stone mason.

Distinctive

His playing was certainly distinctive; the last perhaps in the line of cornet players who performed with a robust bravura that made the most of their innate musicality.

His stamina was extraordinary, and one occasion on arriving late for quartet engagement in a local band club he apologised and asked the people to remain in place as he played his full repertoire of cornet solos. He gave his £5 fee straight back to the band.

Alongside Sir Adrian Boult, Willie said, “…they opened up the beginning of a new, wider musical world to me.”

It was the figure of Sir John Barbirolli that changed everything - with an invitation to play third trumpet with the Halle Orchestra in 1953. Alongside Sir Adrian Boult, Willie said, “…they opened up the beginning of a new, wider musical world to me.”

Great regard

He quickly became principal trumpet (although he managed to play with Ferodo on their 1955 Belle Vue victory) and stayed until 1961. The charismatic conductor held him in great regard and the prominent first trumpet part of Vaughan Williams’ ‘Symphony No 8’ (dedicated to Barbirolli) was specially written for him.

A short stint with the BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra was the prelude to his appointment as co-principal trumpet of the London Symphony Orchestra.

Enjoying the orchestral life

Impressive

It was later recalled that the orchestra’s members were rather surprised at the appointment, with Denis Wick (principal trombone from 1957 – 1988) revealing: “Before hearing him, I personally had some misgivings and I suppose some degree of snobbery about brass band styles of playing, although Bill’s pedigree as a player was impressive.

From his first appearance, it was clear that his brilliant technique and musical awareness made Bill a spectacular, if somewhat unorthodox, first trumpet player. Within a very short time, he commanded the utmost respect from the entire orchestra”.

Finest

His performance of the post horn solo played on flugel on Jascha Horenstein’s recording of Mahler’s ‘Third Symphony’ is regarded as one of the finest ever, as was his playing on Copland’s ‘Quiet City’.

From his first appearance, it was clear that his brilliant technique and musical awareness made Bill a spectacular, if somewhat unorthodox, first trumpet player. Within a very short time, he commanded the utmost respect from the entire orchestra”.

Bold, full in tonality and fearless in approach, he led the way for a brass section at the LSO that with the arrival of Maurice Murphy was to become legendary.

He later remarked that once under the baton of Khachaturian he was playing for six hours a day, “…blowing my guts out. It took me back to the old days at Black Dyke.”

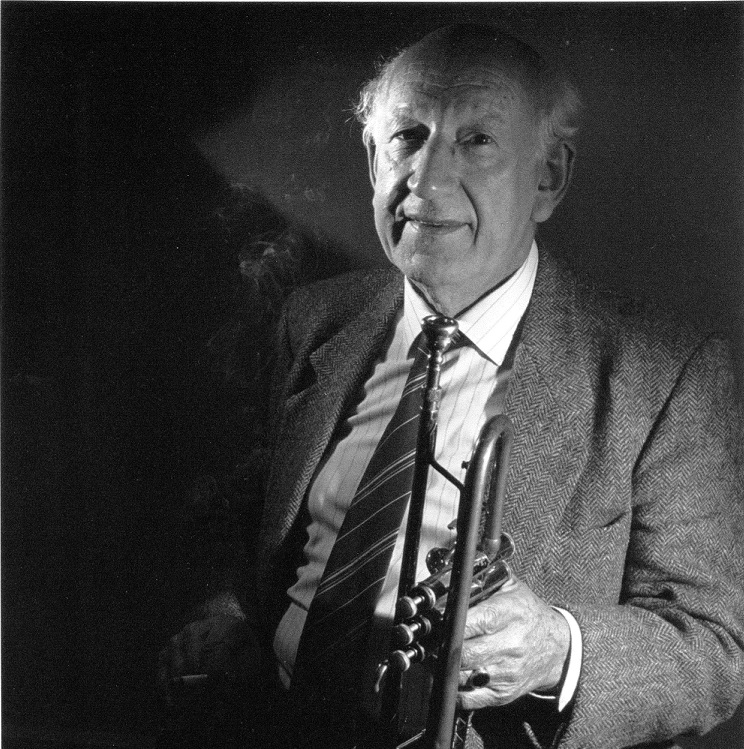

Ready with a tale or two...

Good night

That connection between them sparked many memorable stories – as well as perhaps some of Murphy’s later contretemps with leading conductors.

Willie though was more than capable of standing his ground – once famously telling George Solti in his broad Yorkshire dialect as he left a particularly fraught rehearsal; “Why don’t thee f*** off you bald - headed Hungarian c***”.”

The conductor, not understanding the accent, smiled as he was told by the quick-witted lead violinist that he had just been wished a “very good night”.

The conductor, not understanding the accent, smiled as he was told by the quick-witted lead violinist that he had just been wished a “very good night”.

During the 1970s the LSO became a much in demand film orchestra – and Willie Lang’s powerful sounds coulld be heard on numerous releases of the era. After 27 years he eventually moving down to second trumpet before he took the decision to retire back home to live in Harrogate with his wife.

Rare return

Having left brass banding in the 1950s he seldom returned, although he became much loved tutor for the National Youth Brass Band of Wales (as well as a hugely respected visiting tutor at London Academies) and played with the BTM Band at the National Finals – his payment reportedly made in bottles of his favourite whisky.

In 1987 he joined Maurice Murphy, James Shepherd and Phillip McCann for a memorable performance of the appropriately named ‘Legends’ at the British Bandsman Centenary Concert, written by Elgar Howarth.

In later years however he was dogged by ill health – his life-long smoking habit (many an orchestra stand was marked by the burning embers of his unfinished cigarettes) bringing a cruel end to his ability to play, as well as to tell those great tales of a remarkable life.

Willie Lang died on Thursday 14th December 2006, aged 87.

Tim Mutum with thanks to John Clay, Derek Rawlinson and Chris Helme.

4BR Hall of Fame: No.1: Jack Atherton

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2019/1832.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.2: Albert Baile

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2019/1836.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.3: Stanley Boddington

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2019/1842.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.4: Bram Gay

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1848.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.5: Leonard Lamb

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1855.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.6: Arthur Stender

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1866.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.7: Violet Brand

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1871.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.8: Eric Bravington

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1875.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.9: Norman Ashcroft

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1879.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.10: Albert Chappell

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1884.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.11: Betty Anderson

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1889.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.12: Trevor Walmsley DFC

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1897.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.13: Percy Code

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1903.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.14: George Thompson MBE

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1909.asp