The gamblers that won the lot: Grimethorpe Colliery Band in 1985

35 years may now have passed, but the peculiar genius of Grimethorpe Colliery Band’s 1985 Granada Band of the Year winning performance hasn’t lost an ounce of its impact.

The sheer audacity of it all still makes you smile with pleasure.

Colossal gamble

Described as a ‘colossal gamble’, it was a musical wager devised by Elgar Howarth that claimed the pot and brought the house down; a bluff hand that beat the busted flushes of rivals with nothing more than the wit, daring and the sheer hutzpah brilliance of the performers themselves.

It remains an iconic moment in contesting history.

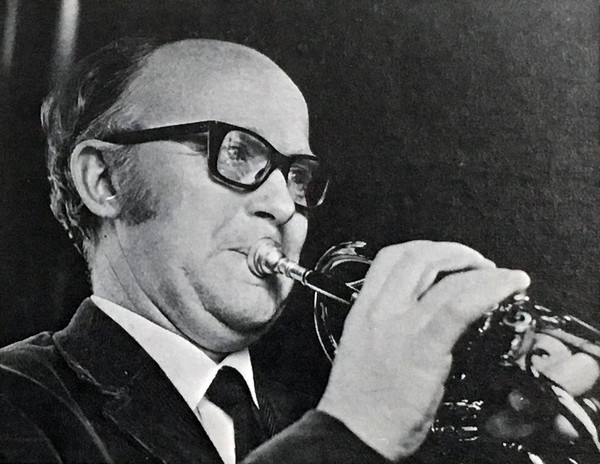

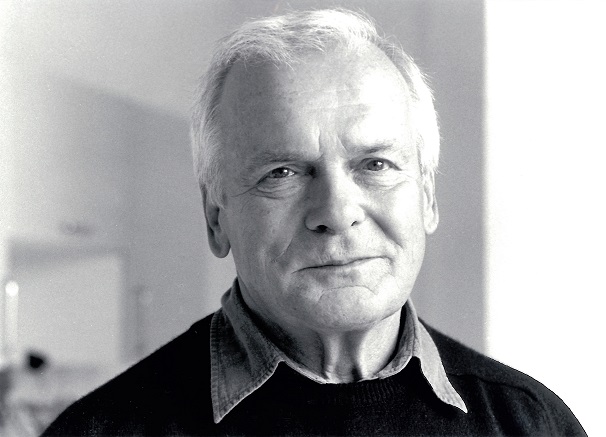

The genius behind it all: Elgar Howarth

Only Grimethorpe and Howarth could have done it – arguably the ultimate interpretation of the event’s ethos, which Bram Gay, writing the foreword to the first contest in 1971 said was to provide; “a programme for television presentation at a peak period, taking into account the need to retain the audience while promoting the brass band as a medium not only of entertainment but of musical communication.”

Described as a ‘colossal gamble’, it was a musical wager devised by Elgar Howarth that claimed the pot and brought the house down; a bluff hand that beat the busted flushes of rivals with nothing more than the wit, daring and the sheer hutzpah brilliance of the performers in its hand.

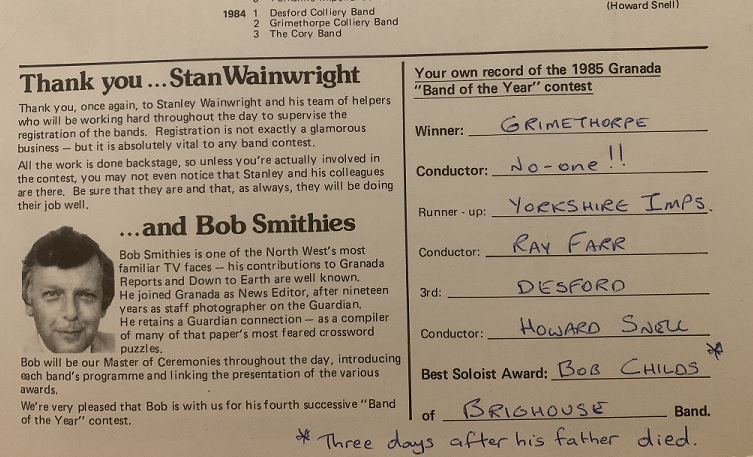

The audience lucky enough to have been at the Spectrum Arena in Warrington on 8th June 1985 - including the future 4BR Editor and a car load of players who travelled to support Bob and Nicholas Childs (Bob won the ‘Best Soloist’ award with Brighouse; Nick played with Grimethorpe) following the death of their father, was left mesmerised.

Shock wave

That though was nothing compared to the effect of the shock wave that followed.

A week later (these were pre-internet days remember) Peter Wilson, Editor of the British Bandsman reported that it was “possibly the most colossal gamble ever taken on a contest stage”; “outlandish” and a “foolhardy ploy”, “nothing profound” with playing “a bit on the loose side” despite “the flair and quality”.

He summed it up with: “Hopefully we will not see it again.”

It was an equally colossal piece of acidic snobbishness.

The contest organiser Bram Gay called the Grimethorpe Band win a 'bodyline blow'

Meanwhile not to be outdone, in a splenetic analogy to test cricket’s most infamous controversy, Bram Gay called it a “bodyline blow”.

It transpired he had threatened Grimethorpe with disqualification on the dubious grounds that they hadn’t been conducted on stage by David James (other than for the last four bars of the programme).

He failed to mention he wasn’t even listed in the programme as their conductor (Ray Farr being printed).

He later reportedly said that there would be change in the rules to prevent bands “making a fool of themselves”.

He later reportedly said that there would be change in the rules to prevent bands “making a fool of themselves”.

Artistic presumptions

Bram Gay had form on Grimethorpe.

In Arthur Taylor’s 1984 book, ‘Labour & Love’ he spoke of the “sheer idiocy” and “absolute tomfoolery” displayed by some bands in the early years of the Granada Festival. Those who knew him knew whom he was talking about.

He never hid his distaste for what he once called their “artistic presumptions.” The accusation was directly alluded to by him again in the foreword to the last contest in 1987.

The pre-digital age of entertainment contesting...

The reality wasn’t anything of the sort - but it was the culmination of the partnership between Grimethorpe and Howarth that changed the face of entertainment contesting; one that started with victory at the 1972 event and ended here with him reluctantly beckoned onto the stage to finally lift the imposing Granada Trophy above his head in triumph.

The controversy hurt him - greatly. He never got involved again. Grimethorpe never won the contest again either.

Considered analysis

When misplaced passions had finally subsided, Tom Aitken wrote a considered analysis of the victory in the monthly ‘Brass Band News’, summing up things succinctly by saying: “In a world which is often dull it is good to see audacious risks being successfully taken.”

1985 was a pre-technological era of banding. The mobile phone was in its infancy, social media confined to a person reading the Daily Mirror over a friend’s shoulder. The internet was still scientific theory.

1985 was a pre-technological era of banding. The mobile phone was in its infancy, social media confined to a person reading the Daily Mirror over a friend’s shoulder. The internet was still scientific theory.

That said, entertainment programmes were being brought into the post-industrial age – thanks to the likes of Howard Snell, Ray Farr and Howarth himself who explored new musical avenues with their arrangements and compositions.

However, the template for success seemed impervious to change: Flash opener, solo, a touch of tradition, something funny followed by something reflective, big finish. Variation came with the occasional genre detour a few funny hats and stilted choreography, but basically that was it.

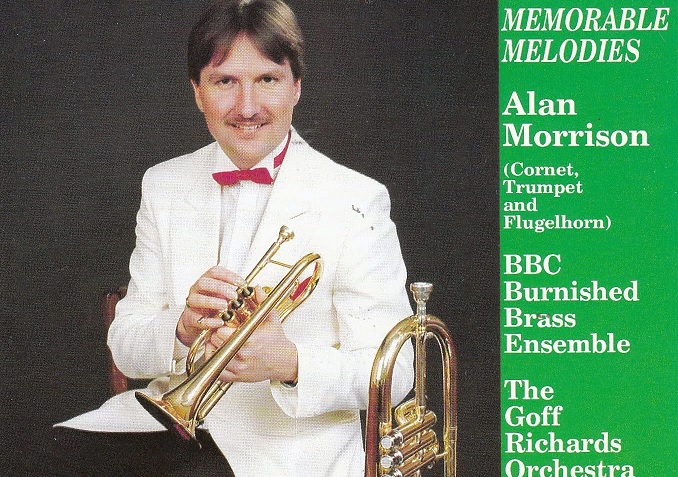

A young Alan Morrison was the spotlight featured soloist on the day

Template for revolution

Never afraid to challenge perceived orthodoxy Howarth presented his template for revolution at a cold Grimethorpe rehearsal in early January.

“We were getting a bit fed up being beaten by Desford,” principal cornet Alan Morrison recalls when now looking back.

“Elgar Howarth came up one evening to discuss Granada with us, and I think he could tell we needed something to give us a spark again as the Miners’ Strike still wasn’t at an end.

At that stage all he insisted on was that we would be 100% behind his idea – no arguments, no changes of mind. There were plenty of strong minded characters in the band at the time, but such was the respect we had we would have played dustbin lids for him.

When he told us what he had in mind we jumped at it.”

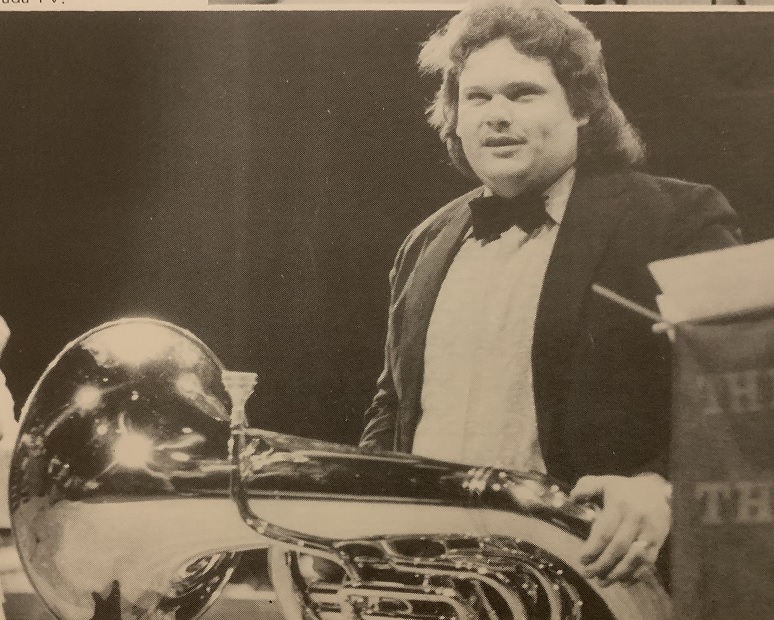

Grimethorpe's tuba star Steve Sykes provided the initial focal point of the performance

The initial focal point of the performance was to be the Eb tuba player Steve Sykes.

“Mr Howarth – always Mr Howarth, treated us as he did the finest professional orchestral musicians; he never patronised or tried to impress. He simply explained what he wanted and how to achieve it; never questioned our abilities as players, or musical insight. He listened when we asked questions and explained how to work things out.”

Treasured possession

One of Steve’s most treasured possession is an A3 sheet of paper given to him by him that laid out his thought process – right from the moment he had to walk onto an empty stage to start his own ‘personal rehearsal’ on ‘Lucerne Song’.

And such was Howarth’s forensic approach that he also went on to provide the Granada production team with no less than 16 pages of camera shot instructions.

“I’ve got it framed and it’s tucked away somewhere, but it was a perfect blueprint of his imagination,” Steve said. “…from the music choices to where we stood, how we moved from piece to piece to how we finished things off.

What he wrote down and gave us at the first rehearsal was what we did on stage. It was an incredible insight into how he worked.”

Such was Howarth’s forensic approach that he also went on to provide the Granada production team with no less than 16 pages of camera shot instructions.

As the band members were still on strike in early 1985, time was on their side, although when they did return they kept up a strict rehearsal schedule. Secrecy was also key.

Although there were no social media platforms or mobile phone text messages at the time, the Yorkshire rumour mill still worked overtime.

“Mr Howarth insisted we did this for ourselves – not others,” Alan said. “Closer to the contest we rehearsed in the local Grimethorpe Institute because we needed the space."

Something special

He added: "It was a strange feeling I had getting on the bus to travel to the contest. I don’t think any of us was bothered too much about what the result would be – we all felt we were either going to win or come last! Nobody outside the band really knew what we were about to do. But we all knew we were going to do something special.”

The only question some players had was about the difficulty of the music. The opening ‘Lucerne Song’ was to see Steve take to the stage himself, followed by the players as if they were coming into the rehearsal and joining in.

With no conductor to be seen, the band then led itself through Rimsky Korsakov’s ‘Dance of the Tumblers’, ‘Eterna’ by Garozza (arr Howarth) , the ‘Harry James Trumpet Concerto’ featuring Alan as soloist, the traditional air ‘Joan Glover’ (arr. Howarth), the ‘Farandole’ from Bizet’s ‘L’Arlesienne’ suite and the return to the lone ‘Lucerne’ tuba player as colleagues one by one bade him farewell.

All the band had to play their part in full...

The ‘sting’ followed: Just when things seemed to be coming to an end, on marched the band with David James tapping his watch in disgust to smash out the final few bars and bring the audience to its feet.

“The only thing that worried us was that someone would put the wrong music on the wrong stand. That would have meant disaster as there was no fixed position for any player,” Steve recalled.

“The music was may have been simple to play but it was anything but on stage. It took great discipline and musicality too. Just listen to Pete playing on ‘Eterna’ and the band playing on ‘Jane Glover’ – that took some doing.”

Practice made perfect

As for the choreography – practice made perfect.

“Elgar Howarth returned regularly to check on progress and David James ran the programme through time and time again,” Alan remembers. “Little things were sorted out – such as getting Stan to direct segues between some items, and for me to be able to bring the band in when playing my solo.

Each player knew exactly what they had to do. The attention to detail and the little added extras and touches of humour were all rehearsed. By the time we were all on stage we had the audience in the palm of our hands.”

Each player knew exactly what they had to do. The attention to detail and the little added extras and touches of humour were all rehearsed. By the time we were all on stage we had the audience in the palm of our hands.”

Vinko Globokar

Alan thinks that Elgar Howarth’s idea of the performance choreography may also have come from a surprising source though.

“We did a short tour to Yugoslavia and did a concert where we performed a conceptual work by Vinko Globokar in a car park in Zagreb which needed plenty of space to move around. I don’t know how that would have gone down at the contest, but the idea was there for him.”

Grimethorpe Colliery Band had played choreographed music by Vinko Globokar

Steve agreed. “Elgar Howarth led us on such exciting musical explorations, so this wasn’t anything new. As a result we had complete trust in each other.

All I had to do was play what he had asked me to do – although that was to try copy what the great John Fletcher did with ‘Lucerne Song’ with the Philip Jones Brass Ensemble!”

He added: “I remember that there was such a buzz of anticipation about the hall when I started to play – I could feel it in the air (There were still people coming into the hall to find their seats when he started playing). It just grew and grew. When the band came on to close things off it just exploded.”

No foregone conclusion

The result though was not a foregone conclusion, as was later revealed.

Earlier, defending champion Desford had also produced a choreographed programme that featured the first appearance of Howard Snell’s famous ‘Two Cats’ duet, as well as an arc of cornets in his arrangement of Bach’s ‘Air from the Suite in G’.

A rather frenetic ‘Carnival Romain’ finisher had scuppered their chances though of a fourth successive victory as they eventually ended third, whilst Ray Farr and Yorkshire Imps gave a robust showy set – from Indiana Jones to Barry Manilow to come runner-up.

Leyland was fourth, with the rest, with programmes of variations on tried and tested formulas, lagging behind.

Quality of playing

However, given that all the talk was about the visual aspect of their performance, Grimethorpe actually won the title on the strength of the quality of their playing – with the separately closed adjudicators James Scott and Roy Newsome each giving the band top marks over their rivals.

Bram Gay later revealed that when he asked them if they found anything different with band number 9 (Grimethorpe) they were ‘incredulous’ that it was a programme performed without a conductor.

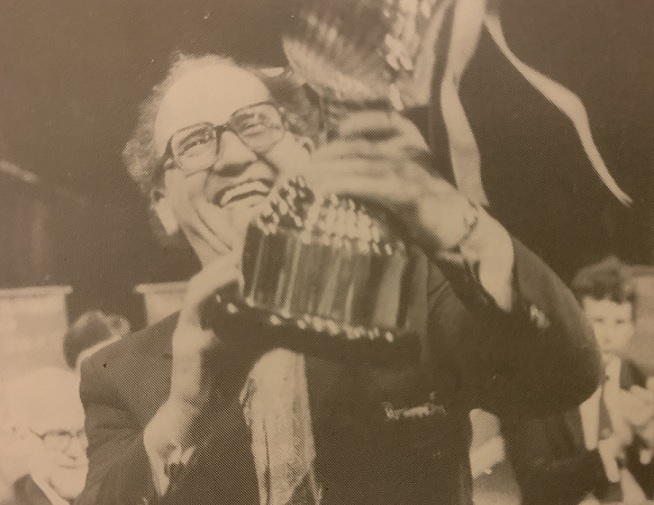

The winning smile tells its own story...

Rather surprisingly it was Granada Band of the Year producer Arthur Taylor (who had been involved in the contest since its inception in 1971) and whose remit was “to react as a television viewer. I don’t want the cloth cap image… just something interesting and entertaining”, that wasn’t that impressed – placing the band equal second alongside Yorkshire Imps in his marks behind Desford.

He reportedly got “fed up with the manoeuvres”, saying that “he had seen it all before”.

whose remit was “to react as a television viewer. I don’t want the cloth cap image… just something interesting and entertaining”, that wasn’t that impressed – placing the band equal second alongside Yorkshire Imps in his marks behind Desford.

And when later asked about the ITV broadcast he said it would be “quite good I hope”, although he added that he felt that it “wouldn’t be taken seriously by music lovers” and “that it should never happen again.”

Mattered little

It mattered little to Grimethorpe.

“We were more pleased for Elgar Howarth than anyone else,” Alan said. “When he was asked to come onto the stage to lift the cup you can see him saying that it was the first time he had even touched the trophy despite winning it three times before.

It was his genius that won that contest.”

The winners prepare to take their bow

High point

Steve agrees. “We had already heard the gripes of some rivals and officials, but we didn’t care. It says a lot that when we did the lap of honour performance the hall was still packed unlike previous years at Belle Vue – with lots of players from other bands taking up seats in the hall.

The only disappointment was that the television broadcast didn’t really capture the magic that was on stage – it was cut between the contest and lap of honour performance. People still come up to me to talk about it though – so that tells you something.”

Grimethorpe winning performance was arguably the high point entertainment mark for the contest – one which despite their inventiveness couldn’t save it from the television axe after the 1987 event in the Isle of Man.

Perhaps Arthur Taylor knew all along. Brass bands were simply not entertaining enough.

Aftermath cameos

The aftermath did produce a trio of cameo memories well worth remember though – the first just a few months later at the British Open at the Free Trade Hall, as Steve recalls.

“We were waiting to go on when I jokingly asked our MD Geoffrey Brand if I should walk on by myself – just like Granada.

He was a very serious musician, but he looked back at me and said “go on then”.

And I did – much to the amusement of the audience who got the ‘joke’, but not to Harry Mortimer who I could hear shouting from the wings; “Get that bloody fool off the stage!”

And I did – much to the amusement of the audience who got the ‘joke’, but not to Harry Mortimer who I could hear shouting from the wings; “Get that bloody fool off the stage!”

Two months later the band reprised the performance at Brass in Concert - but the number 1 draw (made on the morning of the event) meant they had to perform the ‘National Anthem’ in traditional seated formation and include a march. They came third.

“It was the wrong decision,” Alan said. “All the magic was lost.”

The impact of the victory was marked in a keen listener's programme 35 years ago...

Ultimate accolade

However, the ultimate accolade was given at the 1986 Granada contest, when Steven Mead walked onto the stage to perform, ‘Anything You Can Do (we) Can Do Better’ at the start of Desford’s winning programme.

“There was a great musical respect between Howard Snell and Elgar Howarth,” Steve said.

“So that was perhaps the ultimate nod of appreciation – done with an equally clever touch of wit.”

“There was a great musical respect between Howard Snell and Elgar Howarth,” Steve said. “So that was perhaps the ultimate nod of appreciation – done with an equally clever touch of wit.”

Although there is still debate about the substance of what Grimethorpe ultimately achieved at the 1985 Granada Band of the Year Contest, there is little doubt that its legacy is still felt today with the very best entertainment programmes owing much to their pioneering fearlessness.

Slickly produced, digitally enhanced with multi-media presentation and clever effects they may be, but all owe a debt of gratitude to the man and the band that did all first in an age when technology played a very minor part in the process of inventiveness.

Nothing that has come since has had the sheer audacity to make the same impact.

Iwan Fox

You can enjoy the 1985 winning programme again at: https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=651521682363317