12: Trevor Walmsley DFC (1921 - 1998)

In a modern banding age when personal epithet titles can speak more of vanity than notable achievement, the name of Trevor Walmsley DFC stands as a reminder of the genuine recognition given by a grateful nation for service in the most testing crucibles of battle.

The award of the Distinguished Flying Cross to Flt Lt Trevor Curzon Walmsley (123045) R.A.F.V.R. 105 Squadron was announced in a supplement to the London Gazette on the 17th July 1945.

It followed war time service in the RAF Pathfinder Force which he joined in 1943 as a pilot after serving for two years in the USA as a RAF flying instructor.

The famous wooden framed de Havilland Mosquito combat aircraft he flew had exceptional speed and agility and was used extensively on dangerous low altitude raids.

64 operations

Flt Lt Walmsley flew 64 operations over enemy territory to drop flares and mark out military targets for the aircraft of Bomber Command that followed.

He was involved with the attacks on Arnhem, the submarine pens in Hamburg, the crossing of the Rhine at Wesel, the Battle of the Bulge, the marshalling yards at Leipzig and the dropping of food to the beleaguered Dutch population in Rotterdam and The Hague.

Flt Lt Walmsley flew 64 operations over enemy territory to drop flares and mark out military targets for the aircraft of Bomber Command that followed.

Constantly under attack by ground-fire and enemy fighters, they suffered heavy losses. His DFC summed up the motto of the 105 Squadron which he so bravely served: ‘Fortis in praeliis’ (Valiant in battles).

A professional at work...

As with many of his generation he wore the honour modestly and with deep, respectful thoughtfulness. Too many of his colleagues did not live to enjoy post war careers as successful or as fulfilling as he.

Quiet, focussed and professional in approach, as one bandsman who played under him at the Voluntary Band of the RAF at Calverley where he was posted, said after his death in 1998: “He was a gentleman to all ranks – and a fine musician.”

Self discipline

Walmsley certainly valued those who worked under him as a conductor – noting in an interview for Arthur Taylor’s seminal book, ‘Labour & Love’ that you didn’t need “a sergeant major figure in the middle terrifying everybody into submission. You only get the real discipline when it comes from each individual member’s own self discipline.”

He certainly found that at Yorkshire Imperial Metals – famously leading them to victory at the British Open in 1970 and again in 1971.

“What are we doing here? We don’t earn a living playing in bloody brass bands. What are we doing it for? We’re supposed to be doing this because we enjoy ourselves”.

When the pressure and weariness of preparing for those particular battles seemed tough, his memory (much like that of the great Austrlian cricketer Keith Miller) must have recalled the real pressure of flying a Mosquito over enemy territory as he simply told the players: “What are we doing here?

We don’t earn a living playing in bloody brass bands. What are we doing it for? We’re supposed to be doing this because we enjoy ourselves”.

Cracking cornet player

Trevor Curzon Walmsley was born in Northwich, Cheshire in 1921 and started to play the cornet aged 8. He was taught by his father and eventually became principal cornet of the local I.C.I. Scout Band.

He later learnt trumpet, played with two substantial amateur orchestras and also became principal cornet at the I.C.I Alkaline Works Band, where any notion that he was (in his own words) “a cracking cornet player” were soon dealt a blow as Harry Mortimer was engaged to conduct the band and promptly demoted him to ‘bumper-up’.

He later told Arthur Taylor that when Alex Mortimer conducted “the temperature went up ten degrees”, but when Harry had the baton “it went down ten degrees”.

However, the episode “did me a world of good”, he said. It was to certainly hold the 16 year in good stead for what was to come in his young adult life.

Harry's game

He later told Arthur Taylor that when Alex Mortimer conducted “the temperature went up ten degrees”, but when Harry had the baton “it went down ten degrees”.

Where Alex was exciting but inconsistent in temperament, Harry was “cool, calm and collected.”

It was Harry’s approach that he followed.

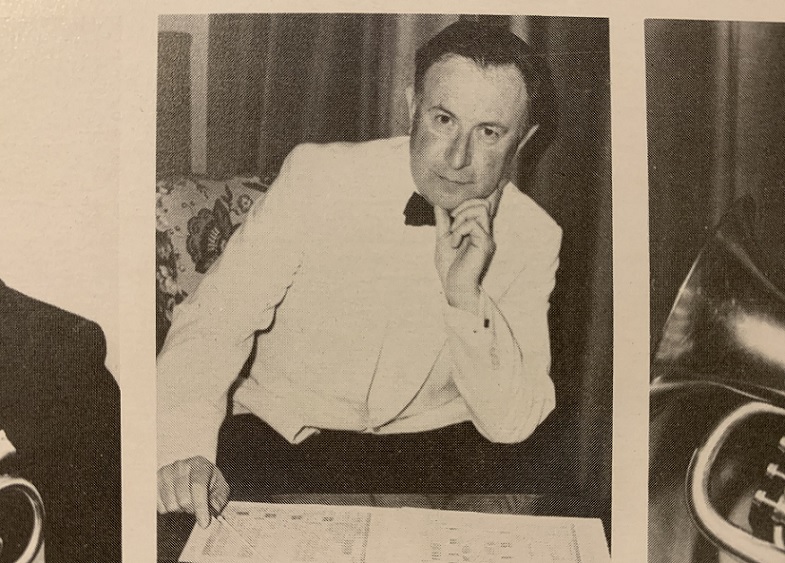

Modest, focussed and respected...

Early success

On his return from America in 1943 he took up conducting to complement his playing in any RAF Station bands and orchestras he could find. It was to be an invaluable learning experience for developing his musical career in future years.

After being demobbed he was appointed Personnel Manager of one of the factories in the burgeoning Philips Group near Croydon, and started conducting his first band – Croydon Borough, leading them to some local success.

After seven years he returned to the North of England, working for a company manufacturing sports equipment, eventually becoming a Director and meeting and working with many leading sports personalities of the 1950s, 60s and 70s. He also pioneered the opening of a factory in India and a second in Pakistan.

His banding apprenticeship saw him conduct the once famous, but now depleted Irwell Springs Band in a bandhall that “had chickens running around underneath the floor”,

His banding apprenticeship saw him conduct the once famous, but now depleted Irwell Springs Band in a bandhall that “had chickens running around underneath the floor”, before the advent of petrol rationing due to the 1956 Suez Crisis saw him offered the opportunity to become Bandmaster at Brighouse & Rastrick, much closer to his home in Ossett where he lived with his wife Brenda.

Ball watching

In the following eight years and under the watchful eye of Eric Ball, his talent flourished – leading Brighouse to top-six finishes at the high quality Edinburgh International Contest in 1958, the 1959 British Open and the North Eastern Area title in 1960.

He was immensely grateful to Ball – “a musical man to the depths of his soul” he said.

Now in demand as a band trainer and professional conductor (he enjoyed spells at Lofthouse Colliery and Wingates Temperance) his next move made his name.

He was immensely grateful to Ball – “a musical man to the depths of his soul” he said.

In 1965 he took on the MD role at Yorkshire Imperial Metals, a band that had enjoyed only occasional success in the previous decade.

Two weeks to 12 years

He initially agreed to go for two weeks. He stayed for almost 12 years. It was to become a period of sustained success that lasted for some years following his departure.

At the 1965 British Open the band came fifth: A year later, and after coming runner-up in the BBC Challenging Brass contest and winning the Edinburgh contest, they came runner-up to CWS (Manchester) at Belle Vue.

They were fourth in 1967, but keen to further improve his ensemble with new signings the next two years saw collective confidence built as they won the Yorkshire Area title in 1968.

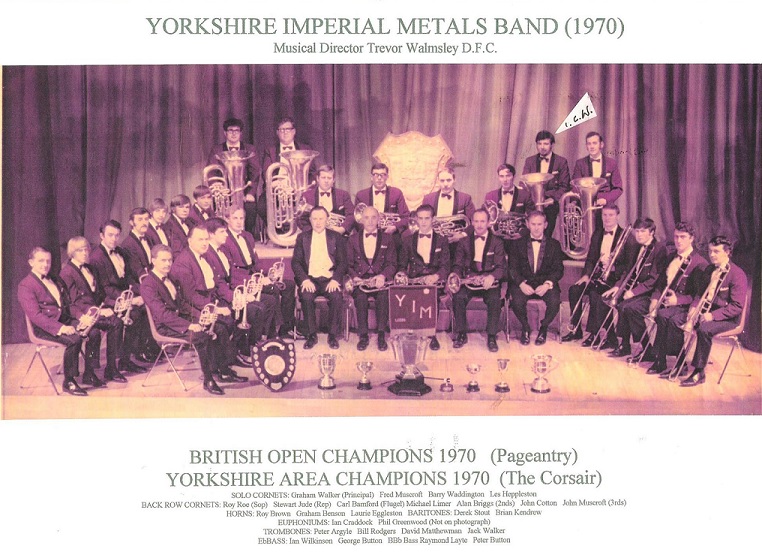

However, by 1970 (when they claimed it a second time) they were as good as any band in the land (they went six years without a major change in personnel).

Not once but twice...

Major success

Finally the elusive major success came at the British Open with a performance of ‘Pageantry’ that the judges, John R. Carr and Jack Mackintosh called “very fine” and “magnificent”. Eric Ball who listened in the audience told his former protégé that it was “magical”.

A year later they successfully defended the title on his ‘Festival Music’; the composer, who as in the box, saying that “there had been inspiration for you today”. Walmsley later said that it was his finest brass band achievement – a repayment of the faith Ball had shown in him those years before.

Although the Albert Hall remained a sparse hunting ground (until 1975 when they came 4th, followed by 2nd under his baton) further Yorkshire Area titles came in 1972, 1975 and 1976.

Factory pride as Imps claimed the Open in 1970 and again in 1971

A historic British Open hat-trick eluded them (coming sixth), although they remained a Belle Vue force in the four years that followed with two podium finishes, a fourth and eighth place.

At the 1973 British Open, Trevor Walmsley was presented with the Iles Medal – the capacity audience greeting the presentation with “warm applause… indicative of the admiration felt for his contribution to brass band music making.”

At the 1973 British Open, Trevor Walmsley was presented with the Iles Medal – the capacity audience greeting the presentation with “warm applause… indicative of the admiration felt for his contribution to brass band music making.”

Almost perfect

His final major appearance with Yorkshire Imps in 1976 very nearly ended in National glory as they came runner-up to Black Dyke at the Albert Hall.

It was almost the perfect way for the partnership to end, but pressures of yet another kind had made his decision as he later related.

“In 1976 economic conditions in industry became such that work began to get in the way of the band, so I gave up work and became, for the first time, a professional musician. I took up the musical directorship of CWS (Manchester Band).”

Yorkshire Imps at the peak of their powers

Despite his best efforts with a number of bands, the following years only brought sporadic success.

CWS (Manchester), coming to the end of its life, was no longer the force of the Alex Mortimer era, whilst Ever Ready, despite their sponsorship security, was unable to make an impression away from their native North East.

Trevor Walmsley still led them to Area success in 1979 and 1980, whilst other bands around the country benefitted from his expertise, skilful man management and cultured musicality.

Last victory

His last victory came in 1985 at the Pontins Southport contest with Lewington Yamaha Band, although he very nearly won a National title in 1989 with Kibworth in the Second Section – only beaten by the 27th and last band to take the stage.

However, by now he had enjoyed a short period as resident conductor of Black Dyke Mills, staying there until he formed the Boosey & Hawkes Brass Band Advisory Service which involved him in visiting bands of all standards in the UK and overseas.

During 1986 he visited Spain several times on their behalf to set up British style brass banding in the country and in the same year published an acclaimed book entitled “You and Your Band – a practical guide to better banding”.

Trevor Walmsley died on 22nd May 1998 aged 76. At his funeral a band made up of players from bands that he had conducted played the RAF march as the coffin left the church.

RAF march

He made his last contest appearance with Carlton Main Frickley at the 1992 Mineworkers Championship and his last adjudication appearance in 1994.

Trevor Walmsley died on 22nd May 1998 aged 76. At his funeral a band made up of players from bands that he had conducted played the RAF march as the coffin left the church.

It was an entirely appropriate final accolade for a man who had given so much in service to his country as well as its brass band movement.

Tim Mutum

With thanks to the Yorkshire Imps Veterans

4BR Hall of Fame: No.1: Jack Atherton

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2019/1832.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.2: Albert Baile

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2019/1836.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.3: Stanley Boddington

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2019/1842.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.4: Bram Gay

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1848.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.5: Leonard Lamb

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1855.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.6: Arthur Stender

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1866.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.7: Violet Brand

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1871.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.8: Eric Bravington

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1875.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.9: Norman Ashcroft

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1879.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.10: Albert Chappell

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1884.asp

4BR Hall of Fame: No.11: Betty Anderson

https://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2020/1889.asp