The most famous face in antiquity...

There is no better mystery of antiquity than that of the Egyptian Pharaoh Tutankhamun.

The last of a royal lineage that ruled during the 18th dynasty of the New Kingdom, the ‘Boy King’ took to the throne following the death of his father Akhenaten at the age of eight or nine (around 1334 BC), and reigned until his death some nine years later.

His tomb was thought lost to the sands of time somewhere in the Valley of the Kings near Luxor, until in 1922, it was discovered by archaeologist Howard Carter (although the steps leading to it were found by a young water carrier) working under the patronage of Lord Caernarvon.

After excavating the rubble leading to the main sealed door, Carter drilled a hole and peered through.

Wonderful things

At first he could see nothing, but then, as he recalled; “…as my eyes grew accustomed to the light, details of the room within emerged slowly from the mist, strange animals, statues, and gold - everywhere the glint of gold.”

He was understandably dumbstruck by the enormity of what lay before him, leading Lord Caernarvon to ask, “Can you see anything?”

“Yes” he replied; “Wonderful things!”

The wonderful things were catalogued by Carter's team

And this was merely an ante-chamber - packed with 5398 treasures and artefacts from chariots and chairs to jewellery and food parcels for the King to snack on in the afterlife.

Thankfully, Carter’s team meticulously recorded it all before a year and half later they broke through a plaster wall and came upon the burial chamber itself.

Encased within three sarcophagi lay Tutankhamun – his embalmed body finally revealed beneath the most beautiful funeral face mask made out of solid gold, lapis lazuli, carnelian, turquoise, obsidian and glass.

Encased within three sarcophagi lay Tutankhamun – his embalmed body finally revealed beneath the most beautiful funeral face mask made out of solid gold, lapis lazuli, carnelian, turquoise, obsidian and glass.

It was the greatest archaeological find ever.

Lurid tales

Soon however, lurid tales were printed of the ‘Curse of the Pharaohs’, as first, Lord Caernarvon and then others reportedly met untimely deaths - although of the 58 people present when the tomb was opened, only eight died in the decade after the discovery.

It was all a load of old Tut; Caernarvon dying of an infected mosquito bite rather than any mummy’s curse, and Carter himself managing to hang on until 1939 when he died of lymphoma.

It was all made up by rival newspapers that had missed out on the exclusivity deal Caernarvon had struck with ‘The Times’.

Still, it was a story that captured the public’s imagination, especially when it was announced in 1939 that a silver trumpet found inside the tomb was to be heard for the first time in over 3000 years.

Tutankhamun trumpet

Still, it was a story that captured the public’s imagination, especially when it was announced in 1939 that a silver trumpet found inside the tomb was to be heard for the first time in over 3000 years.

The ‘Tutankhamun trumpet’ was one of two discovered in the ante-chamber.

One, around 50cms long was made of copper alloy; the other, around 58cms was made of silver.

The bells were of a thinner electrum metal and were around 10.2cm in diameter. Each had a brightly painted wooden core to be inserted to protect it when not in use.

The bronze trumpet and its wooden protective core

The body of the shorter copper trumpet was made of a rolled tube (0.2-0.25mm thick) that expanded in bore size. The longitudinal seam was carefully polished on the outside but left roughly internally. The silver trumpet was made in the same fashion.

At the top end of both the metal had been rolled to form a rounded lip of around 3.25mm thickness, whilst much like modern instruments the bells (which were riveted) were decorated in repousse figures and hieroglyphs depicting the gods Ra-Hrakhty, Ptah and Amun.

Historic broadcast

There was great anticipation therefore when it was announced by BBC radio presenter Rex Keating that he had in fact gained permission for both trumpets to be played for the first time in millennia on what would be an historic broadcast.

However, Keating was no respecter of antiquity.

Despite being told that played correctly the instrument would only produce one note “or at most two”, he later wrote that he was, “…determined to make them produce a simple tune, and this would call for three or four.”

Despite being told that played correctly the instrument would only produce one note “or at most two”, he later wrote that he was, “…determined to make them produce a simple tune, and this would call for three or four.”

The task given was initially given to an unnamed bandsman of one of the Hussar Regiments posted in Egypt and rehearsals were organised.

At the second, Keating recalled that the musician was making “valiant but unsuccessful attempts to extract three notes from the copper trumpet” when none other than King Farouk of Egypt and his entourage appeared.

The silver trumpet and its wooden protective core

The flustered player took to the silver trumpet, but still unsure of just how to play it he inserted a modern bugle mouthpiece and proceeded to shatter it with what was remarked as an “ear-splitting discord”.

According to Keating, the bandsman stood there “a picture of stupefaction”, holding in his hand, “only the stem of the trumpet”. The silver bell had crystallised over 3000 years and had shattered into pieces.

According to Keating, the bandsman stood there “a picture of stupefaction”, holding in his hand, “only the stem of the trumpet”. The silver bell had crystallised over 3000 years and had shattered into pieces.

The curse strikes again?

King Farouk commanded that the instrument be repaired, but not before Alfred Lucas, a member of Carter’s archaeological team was said to have been so distressed that he needed to go to hospital.

Had the ‘curse’ struck once more, especially as the unfortunate bandsman was subsequently ‘banished’ into the heat of desert never to be heard of again?

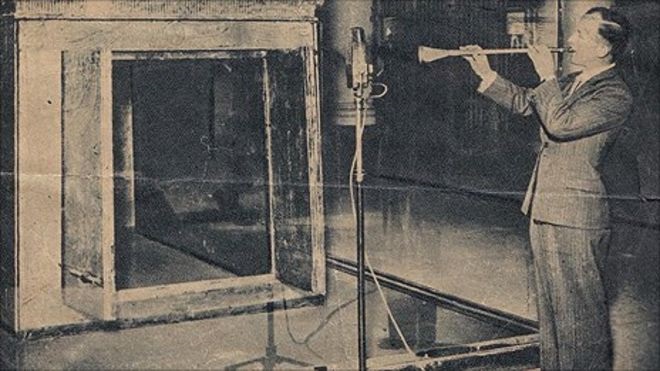

Bandsman Tappern playing the silver trumpet in the 1939 broadcast

Undeterred the instrument was hastily repaired and on 16th April 1939, the replacement player, Bandsman James Tappern of Prince Albert’s Own 11th Royal Hussars Regiment, stepped forward to perform live to an estimated worldwide audience of 150 million people from the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Post Horn Gallop

As can be heard, the event was introduced with the type of Imperial British solemnity as befitting the occasion (and which paid homage to the long dead Pharaoh).

Tappern first played the silver trumpet in front of the microphone, followed by the copper one, although for a fleeting moment you feel that he was going to break into an impromptu rendition of ‘The Post Horn Gallop’.

This time, despite once again inserting a modern mouthpiece the instruments remained intact, producing what musicologist Hans Hickman described as a “raucous and powerful sound”.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HO3P5jkQmgU

It’s a remarkable performance – especially when you listen to the increasing drama that Keating recalls as the minutes ticked down to them being heard. It’s like something out of a Rider Haggard novel…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zr_olu7chEY

Not the sound of history

However, it was not a sound Tutankhamen would have been familiar with, as the instrument was not designed to be played with any sort of mouthpiece at all.

Wall paintings found in tombs showed that the instrument was simply pressed to the lips and blown (the wooden core was neatly placed under the arm), whilst modern reproductions showed that the trumpets produced three notes; a low note with very little tonal power, a well centred middle note (B3) and with some difficulty a higher note of clear pitch (D4).

However, it was not a sound Tutankhamen would have been familiar with, as the instrument was not designed to be played with any sort of mouthpiece at all.

The wooden core protected the bell of the instrument

Later research led experts to believe that it was essentially used as a military ‘call and response’ instrument or blown to keep work parties in order. It is also believed to be a possible lineal descendent of the biblical hatsotserah, similar to that used by the Israelites who left Egypt around the same time.

These were the instruments which Moses was commanded to make (Numbers 10 Verse 2), which were around a cubit long (50cms). The probable date of the Exodus was thought to be only a century or so later than that of Tutankhamen’s death.

Old King Tut

The discovery of Tutankhamen’s Tomb was a worldwide sensation and ‘Egyptmania’ soon became the fashion – even in music.

Unfortunately though the instruments were not heard on the wonderful 1923 recording by ‘The Happiness Boys’ of Billy Jones & Ernest Hare called ‘Old King Tut’, although there is a cracking bit of trumpet and glissando trombone work nonetheless…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=25&v=XImNfGwvepo&feature=emb_logo

Unfortunately though the instruments were not heard on the wonderful 1923 recording by ‘The Happiness Boys’ of Billy Jones & Ernest Hare called ‘Old King Tut’, although there is a cracking bit of trumpet and glissando trombone work nonetheless…

No other ‘Pharaohic trumpets’ have yet been unearthed, with one supposed priceless example displayed in the Louvre in Paris later found to be nothing more than the ornate top of an incense stand.

Tempting fate

As for any curse attached to the trumpets?

No Resurgam call on the trumpet for the Pharaoh for eternity...

Tutankhamen was certainly not resurrected from the dead (he now lies back in his original resting place), although a few months after the first radio broadcast came the outbreak of the Second World War, followed by the Six-Day War between Egypt and Israel when it was played a second time in 1967.

Perhaps tempting fate, one of the trumpets was played again in 1990 which was followed by the Gulf War, whilst the last time it was heard was in 2011 (played by a mischievous member of the museum staff during cleaning), which heralded the Egyptian Revolution.

The bronze trumpet was stolen during these riots, but was returned some weeks later, left in a bag on the Cairo metro with other stolen items.

The miscreant could have been frightened of misfortune after the ‘Al-Ahram’ newspaper printed that the museum curator had said that it had “magical powers” that whenever it was blown “war occurs”.

They can be currently found on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Perhaps understandably, they haven’t been played since…

Iwan Fox