“You’re only supposed to blow the bloody doors off!”

When it comes to the question of ill considered excess, just about everyone can quote Michael Caine’s famous line from the film ‘The Italian Job’.

His resigned exasperation as one of his geezer blaggers employs enough gelignite to take the roof off the Royal Albert Hall, let alone loosen the rusty locks on an old security van parked in the middle of a south London football pitch sums things up perfectly: “You’re only supposed to blow the bloody doors off!”

It was much the same feeling experienced by many sat in the Grieg Hall in Bergen on the weekend.

Shock and awe

Too many bands (especially on their own-choice selections) decided on the ‘shock and awe’ approach to dynamic variance - packing their performances with enough aural TNT to blow a hole in the thick 1970s concrete walls of the magnificent concert venue, let alone loosen the doors off their hinges.

Excessive volume - harsh, metallic and stone cold dead is fast destroying the aural integrity of even the very best brass bands in the world; an imbalanced weight of blubberous, unconditioned timbre sucking all the vibrancy and warmth out of what was once a renowned and richly admired tonality.

As another film icon, Paul Newman remarked in ‘Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid’; “Don’t ever hit your mother on the head with a shovel, it leaves an awfully dull impression on her mind.”

As another film icon, Paul Newman remarked in ‘Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid’; “Don’t ever hit your mother on the head with a shovel, it leaves an awfully dull impression on her mind.”

Not just in Bergen, but across the banding globe, listener’s (as well as judges here in Bergen) heads are now starting to ring as if just being whacked across the noggin for 15 minutes by a navvy’s spade.

Most of all though, it’s become boring; mind numbingly tedious in its monotonous repetitiveness.

The concrete walls came under threat at the Grieg Hall

Easy blame

It would of course be easy to blame the modern breed of composers and their seemingly insatiable desire to include every known percussion instrument ever invented (and some that they could patent themselves).

Writing in 1957 about colour contrasts in brass bands, Dr. Denis Wright (Mus. Doc) pertinently observed that he doubted if, "composers and arrangers for brass have yet exploited all the tonal possibilities, especially when dealing with small groups of instruments playing quietly.”

He went on to add that he felt that percussion instruments “are too often grossly over-employed” and that any composer “who does not know the (brass) band intimately, lacks imagination, or is afraid to experiment.”

Perhaps that still holds true today?

That said, it would still be hard to find a modern brass band score that specifically instructs the timpanist to obliterate the rest of the band by impersonating Japanese Taiko drummers, or a soprano cornet to mimic Maynard Ferguson.

Has the desire to expand the upper limits of the dynamic spectrum of the modern brass bands come at the expense of ignoring the possibilities at its other end?

The clue is in the title...

To be fair, Derek Bourgeois once remarked to someone who questioned the violent dynamic nature of his composition ‘Apocalypse’ - (although not in a Michael Caine accent) - “The clue was in the title.”

That said, it would still be hard to find a modern brass band score that specifically instructs the timpanist to obliterate the rest of the band by impersonating Japanese Taiko drummers, or a soprano cornet to mimic Maynard Ferguson.

Yet, is not beyond the wit of the conductors to employ a subtler soundscape to create anger, fear, darkness, drama and excitement?

Reflection

Many new composers for the medium reflect on the nature of our troubled times, so perhaps it should come as little surprise that there can be a cold, acidic feeling to the music; the emotion laid on with a trowel, the wit, sardonic and cynical, the triumphalism of the final chord heralded by the Pavlovian audience trigger mechanism of an extended tam-tam and timpani roll.

Yet, is it not beyond the wit of the conductors to employ a subtler soundscape to create anger, fear, darkness, drama and excitement?

Does it all have to be so bloody loud?

Are we getting chained to a desire to keep trying to create ever more exotic sounds?

Dynamics are of course relative - and although even the best brass bands are yet to fully encompass a spectrum of Tchaikovsky’s pppppp as in his ‘Pathetique' Symphony to Mahler’s fffff in his ‘Seventh’ - their ability (in part due to bigger bore instruments), in the past few years to widen their scope, has been marked.

It is though at the top end of things that there has been the greatest change.

Forget the theatrical ‘turning-in’ effect that some conductors employ to kid you that their band is playing pianissimo – it’s the ‘turning out’ to directly blast at you at fortissimo that that has a mindless bluntness about it all.

Both have little musical value - an illusion that masks reality; any cohesive sound quality either lost in an asthmatic wheeze or a jet stream of cheap hairdryer sound.

Forget the theatrical ‘turning-in’ effect that some conductors employ to kid you that their band is playing pianissimo – it’s the ‘turning out’ to directly blast at you at fortissimo that that has a mindless bluntness about it all.

Balance

Stylistic considerations also play their part. As much as traditionalists may wax lyrical over the sound created on high pitch instruments of the great bands of the immediate pre and post war periods, the amount of vibrato used for today’s tastes would be considered excessive. Try to replicate that and the soundwave would turn your liver to jelly.

A balance is therefore essential – although listening to many top-flight brass bands trying to play Eric Ball nowadays is like observing an overweight middle-aged bloke trying to squeeze themselves into the front seat of an elegant 1950s British sports car, then stamp his foot on the accelerator only to wonder why it doesn’t take off like a Lamborghini.

Damaging

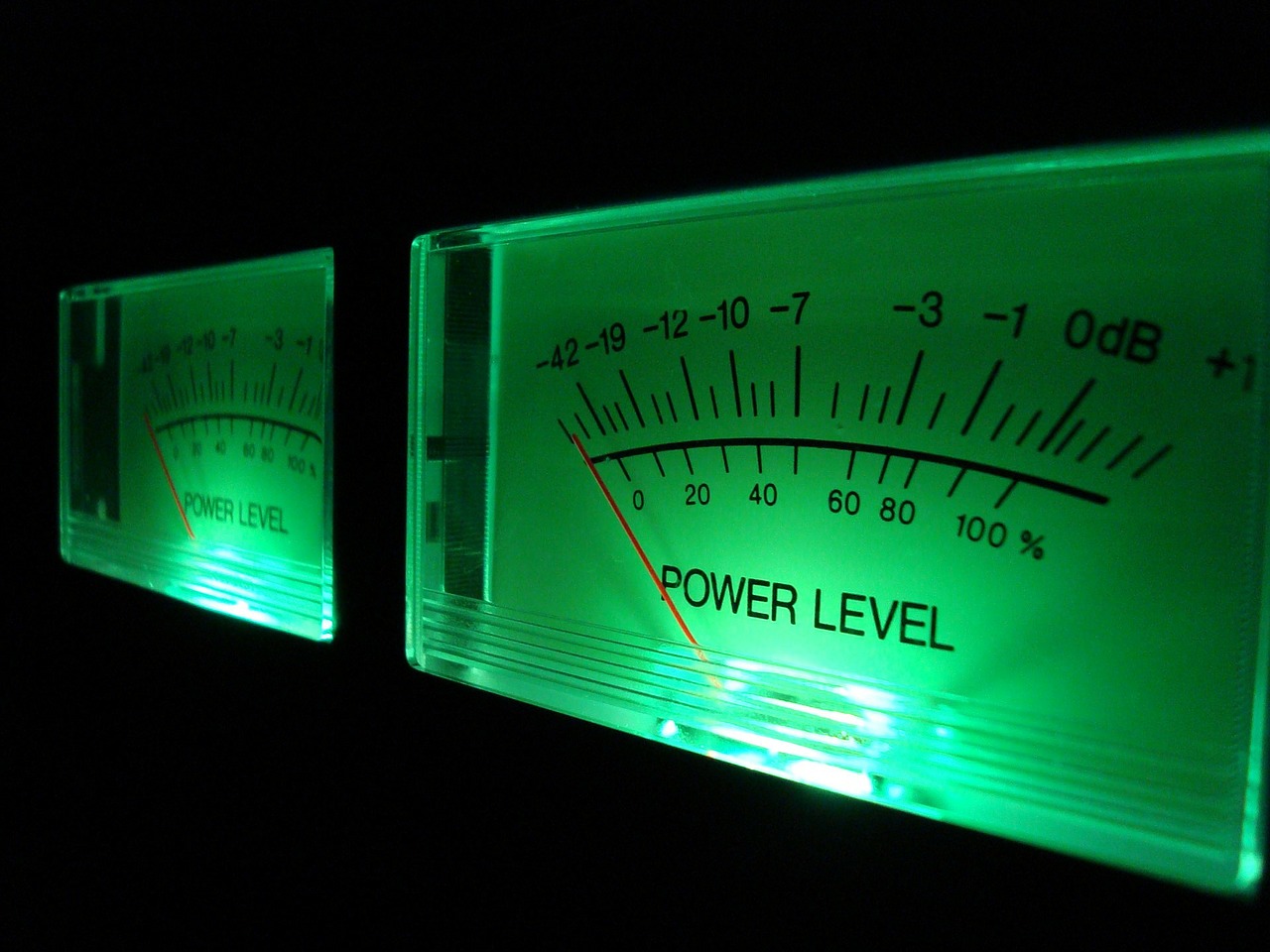

There is little doubt then that 21st century bands are playing ever louder – the decibel levels perhaps reaching damaging proportions.

The Centre for Hearing and Communication that continued exposure to noise above 85 dBA (adjusted decibels) over time will cause hearing loss. According to the National Institute for Occupational Safety & Health, the maximum exposure time at 85 dBA is eight hours.

According to their findings, heavy traffic is 85 Dba, a symphony concert comes in at 110 dBA and a band concert at 120 dBA. That’s the same as the sound of thunder.

According to their findings, heavy traffic is 85 Dba, a symphony concert comes in at 110 dBA and a band concert at 120 dBA. That’s the same as the sound of thunder.

They also report studies that show that 52% of classical musicians have a measurable hearing loss.

However, at 110 dBA, the maximum exposure time is 1 minute and 29 seconds. Now just think how much time is taken up in a modern ‘blockbuster’ test-piece with volume at that level.

The power output has risen in recent years

So are we now also now in danger of damaging our health – and when did this new age of dynamic excess start to happen?

It is hard to pin-point an exact moment in time: ‘Blitz’ in 1980 or ‘Music of the Spheres’ in 2004, ‘Revelation’ in 1995 or ‘The God Particle’ in 2015?

Then again, what about the ‘influence’ of the orchestral interlopers, who supposedly changed the sound of brass bands in the late 1970s and early 1980s?

Supposition

Trying to apportion blame is a needless exercise in supposition, but there is little doubt that we have become increasingly anesthetised to the type of subtlety that was once the staple of the very best brass band music.

For instance, it is becoming ever more difficult to listen to an appreciation in a modern day contest performance of the subtle, relative differences between piano and mezzo-piano, forte and mezzo-forte, the understanding of più markings and that of a decrescendo and a diminuendo.

Everything has become monochrome – shading is fast disappearing.

Brass bands and brass bands music should and must evolve - but it can surely be achieved without losing the essence of why an ensemble of 25 brass and additional percussion players can sound both so utterly beautiful and thrilling.

Derek Broadbent, a musician with years of experience in many different musical genres, once gave a mini-masterclass about dynamic variance and style after a contest where bands had struggled to perform ‘Variations for Brass Band’ by Vaughan Williams.

Much like Derek Bourgeois, the clue he said was in the title; it was all about style as well as dynamic contrast - the two inextricably linked. The players and conductors had all nodded in agreement. The very next contest he later told 4BR, they had all forgotten, or had chosen to forget about it.

Brass bands and brass bands music should and must evolve - but it can surely be achieved without losing the essence of why an ensemble of 25 brass and additional percussion players can sound both so utterly beautiful and thrilling.

Hearing a top class band play loudly, or even very loudly, can be a joy if the sound retains warmth, balance and definition.

It can also be as exasperating as that feeling experienced by Michael Caine when it isn’t.

Iwan Fox