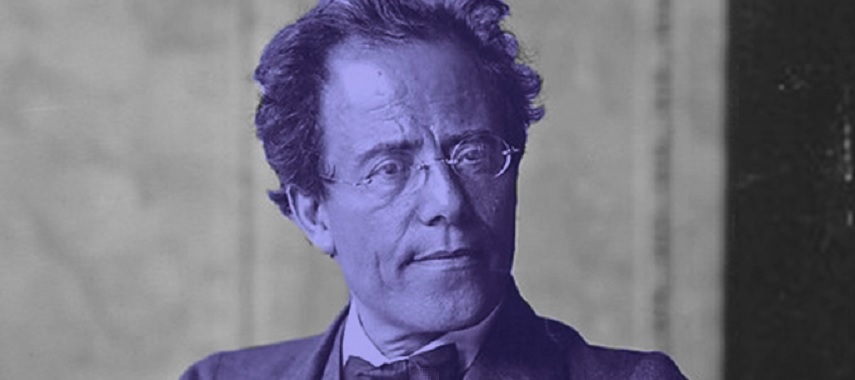

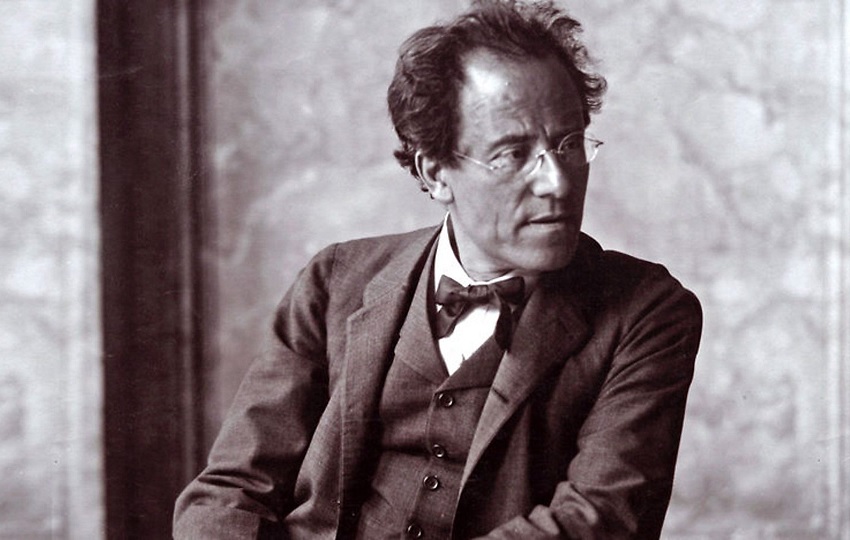

A singular genius: Gustav Mahler

Bold style and a poetic sense of defined character create the absorbing elements of drama, pathos and visceral excitement found in this year’s National Championship set-work.

And whilst Hermann Pallhuber’s ‘Titan’s Progress’ is unmistakably loaded to the gunnels with borrowings from perhaps the greatest symphonist of all in Gustav Mahler (1860-1911), it is also a wonderful example of a free thinking composer bringing his own inventive sense of adventure to the traditional constraints of the test-piece form.

Commissioned by Brass Band Oberosterreich as their own-choice work at the 2007 European Championships, its title is taken from the earliest versions of Mahler’s ‘Symphony No 1’ (which took over a year to compose between 1887 and 1888 and caused the composer titanic troubles of his own).

Unintelligible

Although Mahler originally seems to have had a narrative in mind and had labelled it ‘Titan’, he had it removed by the time the work had reached its definitive four-movement form in 1896, after the critic Otto Nodnagel slated it as ‘unintelligible’.

Nevertheless, Mahler had clearly been inspired by a specific theme, although, despite being an admirer, it does not directly relate to the narrative structure of author Jean Paul’s celebrated 1802 novel of the same name. Mahler was to later point this out.

Although Mahler originally seems to have had a narrative in mind and had labelled it ‘Titan’, he had it removed by the time the work had reached its definitive four-movement form in 1896, after the critic Otto Nodnagel slated it as ‘unintelligible’.

It is more likely that it provided Mahler with an analogy that would help to illuminate his symphonic vision - that of a poetic interpretation of a hero’s life, rather than being a direct singular narrative of Jean Paul’s protagonist, Albano de Cesara.

Expression of hero

According to Mahler’s friend, Natalie Bauer-Lechner, the symphony was to be understood as an expression of the ways in which a strong, heroic person confronts and struggles with the problems of life.

And Mahler had plenty of those in spades - controversy, consternation and even contempt being constant companions throughout his life.

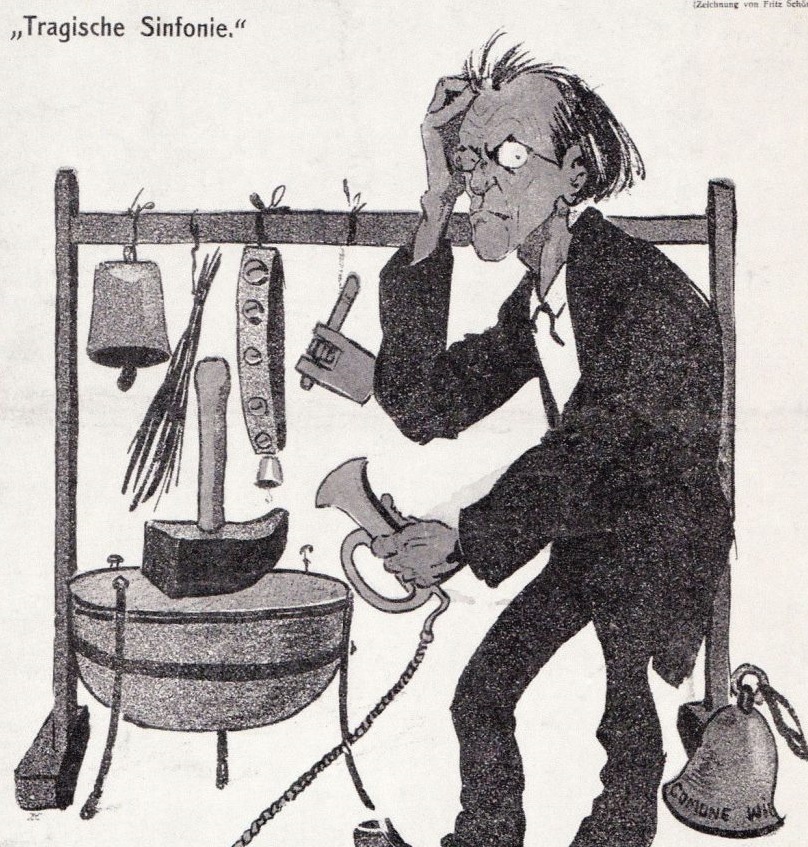

One critic dismissed his Sixth Symphony as, "Brass, lots of brass, incredibly much brass! Even more brass, nothing but brass!”

Also a man of complexities, contradictions, contoversy and contempt

Different lead

‘Titan’s Progress’ takes a different lead (although the brass still dominates)

Where Mahler saw Jean Paul’s novel as an interpretive capstone for his symphony, Hermann Pallhuber uses it as a structuring tool that draws on a great deal of material from the novel itself.

In this senses it is programmatic - and cleverly so. There is perhaps even a touch of Cervantes ‘Don Quixote’ about his central character; his traits also humane, impulsive and comedic as he heroically battles against the tilting windmills of life.

There is perhaps even a touch of Cervantes ‘Don Quixote’ about his central character; his traits also humane, impulsive and comedic as he heroically battles against the tilting windmills of life.

Contradictions

However, like Mahler’s symphony, much of the material is also contradictory in nature.

Mahler had little time for the typical musical conventions of the day, and constantly tried to challenge it with his combinations of symphonic structures that included new instrumentation, folk songs, colloquial dances, and even a funeral march based on a children’s tune.

The adherent disciple: Hermann Pallhuber

Adherent disciple

Pallhuber is an adherent disciple; matching elements that don’t on the face of it match at all.

You hear typical Mahler fourths and fanfares, but also glissandi and ‘inferno triplets’ which pockmark the work in unexpected places. Staccato muted quavers and semi-quavers interject either like bullets shot from a Maxim machine gun or soft droplets of rain on a window pane.

He is also deceptive, almost illusory in terms of pace and dynamic. The use of rubato may seem to be to singularly comic effect at times, but overdone and it becomes gratuitous.

Think of a cheeky wink rather than a lecherous Benny Hill gargoyle grimace.

The use of rubato may seem to be to singularly comic effect at times, but overdone and it becomes gratuitous. Think of a cheeky wink rather than a lecherous Benny Hill gargoyle grimace.

And whilst Mahler may have once exclaimed, “At last fortissimo!” when visiting Niagara Falls, throughout ‘Titan’s Progress’ the dynamic forces are mere tributaries leading to the thunderous cataract of sound that comes at its conclusion.

Much to think about from the composer and for the conductors

Much to think about

Much for conductors to think about then.

It opens dramatically with a short fanfare-like phrase, followed by marked contrasts between merciless aggression and dignified sonority.

The tasteful cornet entry is particularly important; introducing the main chorale theme of the work (based on the famous chorale from the final movement of Mahler’s symphony).

A more playful giocoso section follows, before the drama is ratcheted up at a ‘Presto’ packed with excitement, almost chaotic, as recurring patterns of 7/8, 9/8, and 2/4 give the pulse a restless, agitated feel.

Farandole

A sustained, almost-lyrical section then takes hold; again disturbed by fanfare calls reminiscent of the first and last movements of Mahler’s symphony, before Pallhuber reveals a wicked sense of dry witted humour in a whimsical, if somewhat tetchy ‘Farandole’.

It discombobulates in 8/8 time with quavers grouped in 2 sets of 3 and a 2; a lopsided, ironic take on the form that scurries in the lower brass.

Calm is restored (although interspersed with a majestic if somewhat incongruous soprano herald) with a flowing cornet and ‘distant’ euphonium leads. Once again though, the comedic element is inserted by bizarre folk song ‘oops a daisy’ interjections, like leather-shorted dancers in an Austrian landler waltz (a nod to Mahler once more).

It discombobulates in 8/8 time with quavers grouped in 2 sets of 3 and a 2; a lopsided, ironic take on the form that scurries in the lower brass.

A ‘cheeky’ bum slapping flugel statement brings the music into a quasi-fugue (although not a devilishly fast one), more playful than powerful in conceit, angular and dislocated as it draws on. A brace of spasmodic outbursts finally bring us to the bold finale.

Full heroic voice

Now Pallhuber’s hero is in full heroic voice - energised, emboldened and topped with a falsetto soprano voice that sounds like Barry Gibb of the Bee Gees on steroids.

Mahler isn’t forgotten. All the key themes return in cameo (even the offbeat baritones at the start of the section have the first few notes of the chorale theme) before the massive ‘allargando’ leads us into turbulent flourishes and fanfares.

Now Pallhuber’s hero is in full heroic voice - energised, emboldened and topped with a falsetto soprano voice that sounds like Barry Gibb of the Bee Gees on steroids.

The enormous final few bars, as we topple headlong downward (those inferno triplets one last time) into the maelstrom of a final chord of Niagara sounding volume and power, round off an exciting, complex work in thunderous fashion.

Pallhuber’s ‘Titan’ has done Mahler proud.

Iwan Fox

Thanks to Chris Davies

First Class honours graduate in music from Oxford University, Associate of Trinity College London, and a Licentiate of the Royal Schools of Music.