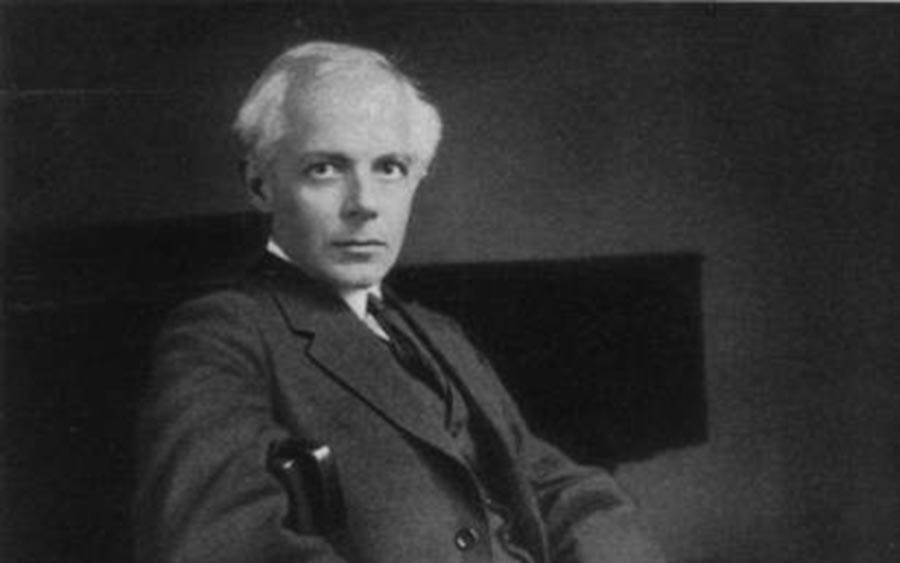

What of the man behind the stare?

Bela Bartok (1881-1945) was not the first composer to write ‘Hungarian’ classical music. Neither was he the first to be influenced by an overwhelming sense of ‘Nationalism’ either.

Nor was he alone in rejecting the tonal basis of composition in the early decades of the twentieth century or a lone voice in refusing to adopt the methodology of the Second Vienna School of compositional thought. Like many he changed his style from an appreciation of Beethoven and Bach to encompass Debussy, Strauss, Mussorgsky and even Schoenberg serialism.

Troubling enigma

Yet he remains a truly unique figure; an eccentric, troubling enigma to categorise and comprehend; doubtful, melancholic, proud, stubborn, cold, depressive - yet able to write music of such glorious luminosity of spirit, atmosphere and confidence.

You can perhaps see why Simon Dobson - both a man and composer you would also have trouble putting a label on, has been able to bring so splendidly to life, his exploration of the Hungarian composer with his thoroughly absorbing, ‘Journey of the Lone Wolf’.

It is a portrait with more than a hint of personal self analysis: Dobson has long confessed his fascination with the composer. He writes as a true believer in a musical hero.

Hard to label: Simon Dobson defies the catergories

Bartok was an excellent pianist and student with a voracious appetite for learning. His early years were scholarly (although he chose Budapest instead of Vienna to study), where he came into contact with the growing ‘Nationalist’ movement and begun to write songs with Hungarian texts.

Maelstroms

In 1904 he heard his first authentic folksong - not Gypsy pastiche as used by Liszt or Brahms - and during the years that followed he worked with his friend Zoltan Kodaly, travelling extensively in the Balkans to record and ultimately preserve a musical tradition that was eventually to be all but consumed in the maelstroms of two World Wars.

Free of spirit

This early period of his adult life - or as Dobson calls it - ‘Capturing the Peasant’s Songs’, forms the basis of the first of three interlinked movements that make up ‘Journey of the Lone Wolf’ (the title comes from Dobson’s own personal text).

This is Bartock free of spirit and constraint (something early childhood illness prevented him from doing); the pioneering ethnomusicologist.

Dobson brings us two ‘dances’ that Bartok might have himself found high in the Transylvanian mountains; one light and fleet footed, the other darker and more ‘macabre’, although each in its own way celebratory in its exuberant individuality.

There is also a scholarly underpinning to the writing here - as the composer certainly pays homage to the very Bartokian elements of the grotesque (comparable to his notorious Allegro Barbaro for piano) as well as ‘The Wooden Prince’.

It is music full of vitality (much like Dobson’s early compositional output) that absorbs atonality and contrapuntal freedom with a bold confidence that strikes your between the shoulder blades.

Disturbing inner core

What follows however is the peeling away of the carapace to reveal a much more disturbing inner core of self-doubt and even self-loathing. These are the years that eventually led to the composer’s isolation in America (he fled there in 1940) - a country that offered freedom from persecution but little else.

Paradox

The composer was a revealing paradox during these years: He sought love and friendship despite his relationships invariably becoming fractious and demanding, whilst his pride cost him greatly (he was financially precarious for much of his time in America, although he all too often refused help).

Concert appearances became increasingly sparse and his fear for the future of his beloved country under an authoritarian pro-Nazi and eventual Nazi occupation filled him with dread.

Even in death Bartok remains an elusive figure to comprehend

Yet during these years his music became ever more glorious; from his strident Piano Concertos and ‘Out of Doors’ (which gives rise to the ‘Night Music’) piano solos, to the stunning ‘Music for Strings, Percussion and Celeste’ with its twisting chromatic theme and the expressive intensity of his ‘Violin Concerto’ and ‘Sixth Quartet’.

Bartok soul

In ‘Night Music’ Dobson is a sympathetic analyst of the Bartok soul - the writing sparse, textured and intense. New sound sources were explored by Bartok during this period, and much of the melancholic atmosphere that emerges from a sombre flugel solo of deep introspection comes from percussion writing that brings an eerie sense of the surreal into being.

It is nightlife that you sense Bartok found disturbing and even distasteful at a time when his home country was suffering so badly: The beauty of the languid writing from Dobson’s pen drips with an ice-cold dispassion; reflections into something of a personal abyss.

Angry detachment

The music shimmers with an aching sense of angry detachment - the cornet, euphonium and most clearly the trombone speak of loss and isolation - personal, physical and emotional. A Tommy Dorsey showcase it certainly ain’t.

The final section ‘Flight and Fight’ explores the final years of quiet neglect in a country that had little appetite to explore music rooted deep in his native Hungarian soil. The latter years of the Second World War promised Americans a free for all consumer boom of lightweight throwaway pleasures based on their own pre-eminent place in the world.

Ebullient works

Bartok was dying of leukaemia. Yet he still completed two ebullient works - the ‘Concerto for Orchestra’ and a ‘Violin Sonata’ - both of which were championed by his ever-decreasing circle of friends, despite little enthusiasm from the composer himself.

It is here that Dobson reveals his own inner rage at the composer’s almost self-willed isolationism, with a series of pulsating, intertwined ideas of increasing complexity and almost wild abandonment. It is as if he is trying to drag the moribund soul of Bartok back to life through a force field of impassioned energy.

As throughout, it is wonderful, sweeping writing for brass band - packed to the gunnels with drama, pathos and passion.

Even as you see in your mind’s eye Bartok’s coffin lowered into its grave, surrounded by the pitiful sight of a handful of mourners, you are still totally engrossed by a wonderfully mature work for the brass band medium - one that closes with a ‘bitter sting’ of anguished despair.

Iwan Fox