Iconic imitation: Tredegar Band in 1977 as the Cyfarthfa Band of the 1860s

It has been good to read Jack Goldstein’s article on 4BR, and I agree with the points raised regarding the marginalisation of brass bands.

However, his viewpoint is largely based on socio-economic and historical observations, and I feel it may also be useful to consider brass bands in the wider musical world in which they have operated for close on two centuries.

In their infancy there was no published music written for the medium. Instead, arrangements of works were made usually for functional purposes; dances, parades, civic functions etc.

Brass Bands were a utility item; mobile, cheap and, to some extent, musically versatile - hence their subsequent adoption, as Goldstein says, by well-meaning morally forthright industrialists.

And the original Cyfarthfa Band in 1905

It also meant that from the outset the basis for brass bands to become musical imitators was in place.

The main source of early musical material was orchestral repertoire - leading to the question of how and where brass bands fitted into the genre of so-called, ‘popular music’ of its day.

This can be defined as music enjoyed by a large proportion of the public, but also as having the commercial intent to make money for its providers. Sheet music was printed in large amounts to necessitate profit as well as performance.

The Victorian Ballad

The obvious performing medium was the human voice with accompanying instrument - usually the piano, but also with harmonium, organ, accordion, concertina and even banjo. The Victorian ‘Ballad’ became the pop song of the era.

So what about brass bands?

Their popularity also came through performance - although it was often said that it came at the expense of being the ‘poor man's orchestra’ - implying an obvious imitation of another musical genre. Programmes of the age reflected this; consisting largely of classical music transcriptions, hymn tunes, popular tunes, marches, solos and dance music (especially the waltz).

The March

The earliest musical form to have attracted specific compositional expertise was the march, but it is unlikely that the general listener would have discriminated between a march written for a brass band and one transcribed for it.

Even so, brass bands before the age of electronic amplification were not suitable for solo vocal accompaniment, although accompanying choirs has always remained viable: So how did they try to create a niche or ‘originality’ for themselves in the mind set of the general musical listener?

This lay predominantly in the hands of brass band promoters who, of course, had a financial incentive for their efforts.

Labour and Love

Some original works had been written for the medium from its earliest days, usually by ambitious (or misguided) bandmasters. However, these simply reflected or imitated the general (borrowed) repertoire.

Even ‘Labour and Love’ by Percy Fletcher is an interesting example of this.

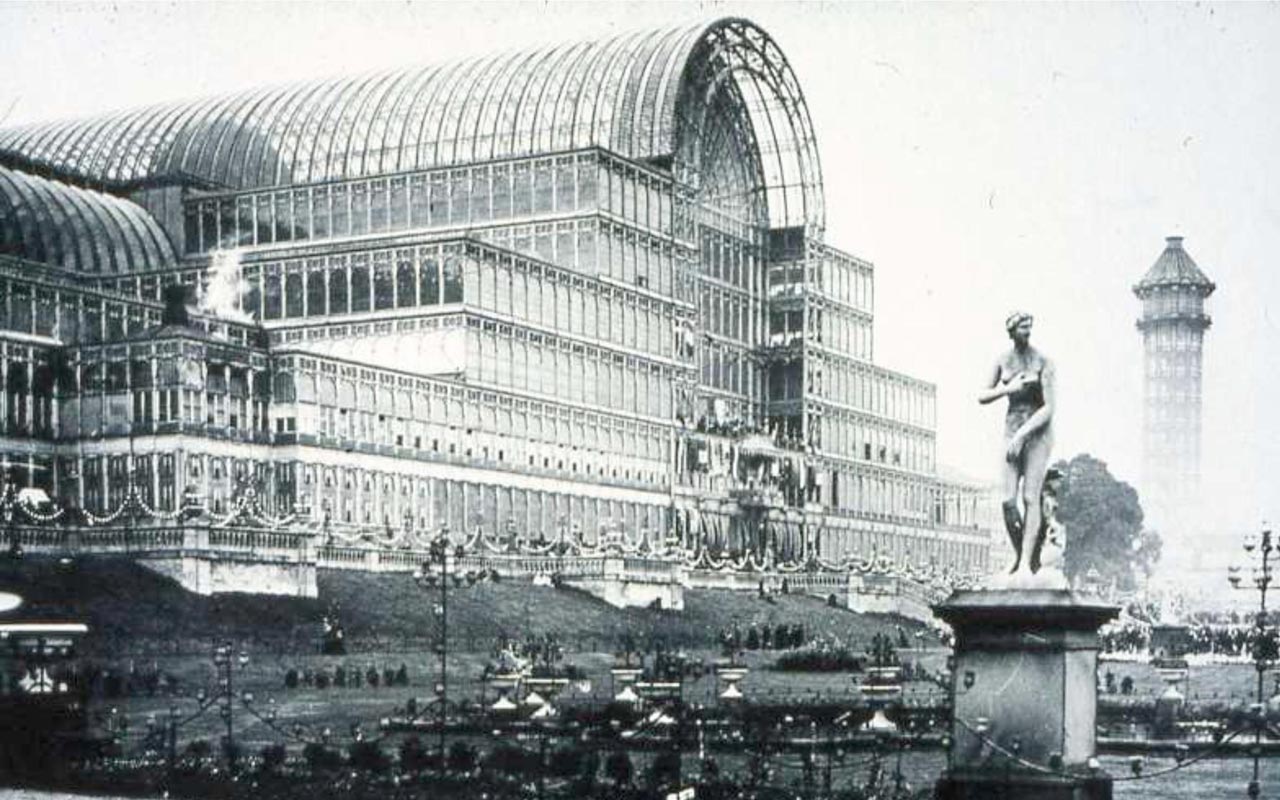

Commissioned for the 1913 National Championship at Crystal Palace (a fact perhaps only relevant to those involved in brass band contesting rather than the wider listening audience for brass band music), the work was essentially an imitation of the operatic genre of the time.

Imitation at a great original: Labour & Love at Crystal Palace

It also provided a pointer as to where brass bands were now heading in the wider musical world in the first half of the 20th Century.

Fletcher was primarily a ‘light’ classical music composer - a genre that provided the core material for brass band repertoire - and one that the general public could easily identify with.

One offs

Some later attempts were made, usually disastrously, in terms of more ambitious transcription and performance to imitate the big bands and dance bands - the undoubted ‘popular’ music of the later Edwardian age.

This was also the age of ‘original’ compositions for the medium by the likes of Elgar, Holst, Bliss et al.

Not viable

These works were invariably commissioned as test-pieces and were largely ‘one-offs’. With no offence intended, mainstream orchestral composers have generally not been persuaded to undertake a series of brass band compositions simply because ‘they wanted to’. It is not commercially viable - and everybody needs to make a living.

A missed chance of a serial brass band composer: Gustav Holst

Even after the Second World War, an examination of music publishing catalogues throws up names such as Jack Beaver, Leighton Lucas and Peter Yorke - all of whom composed primarily for light orchestra. Their original works and arrangements for brass band reflect this - clever imitations of style and character.

Distinction

There is also another distinction to be made at this point: That of the occasional listener to brass band music making and those interested in brass band contesting per se - although these may overlap.

In reality, the phrase ‘Brass Band Movement’ refers primarily to brass band contesting, and this in no way can be considered a ‘popular’ musical activity - neither now or in the past.

This links in with Jack Goldstein's well made point that brass bands in essence simply form a small part of people’s overall musical awareness, rather than a substantive part of any engaged interest.

Original creativity: Rambert Ballet with Tredegar Band in Dark Arteries

So where does this leave brass banding now?

In my opinion, pretty much where they have always been and probably always will be: A form of music making of interest to a minority of the population: No different from that experienced and enjoyed in the Victorian age.

As I have suggested in my article, the reason has been our reliance on imitation - a method of musical survival that does enough to keep its head above the water with each passing generation.

Original creativity

There have been attempts to try and employ original creativity (such Tredegar Band with the Rambert Ballet), but with imitation as the basis of our musical foundation, it is difficult to see how a genre of music specific to the brass band could ever have, or can ever become, more widely recognised.

However, this is not sounding the death-knell as others have argued.

It is simply suggesting that brass bands have always been a minority interest ensemble in the wider musical world - although now may be the last time we can take progressive steps to broaden the base of that listening appeal.

The obstacles as Jack Goldstein pointed out are many and ingrained, but as Herman Melville once said, ‘It is better to fail in originality than to succeed in imitation’.

Paul Gomersall

The Author:

Paul Gomersall

Paul was educated at St Andrews University and is a former amateur trombonist and conductor of brass bands in the North East of England. He admits to esoteric musical tastes and has been a keen and active follower of the brass band movement over the last 50 years.