A composer of horizons and vision

Chris Thomas: Could you tell us something about your working methods.

Do you tend to have a ‘vision’ of a piece in its entirety before you commit anything to paper?

Nigel Clarke: I think my working method has developed substantially in recent years. I’ve found an approach that is not easy and very time consuming, but does achieve results.

It’s much like a sculptor: The music is inside the slab of marble and it’s a matter of finding it; then, shaping, continually sanding away and finally spending many weeks, days and hours polishing it.

I always write about a specific subject and I almost always write for musicians that I know and trust.

These days I also almost always write outside of my comfort zone.

I was a late starter in many ways and I try to make every work count rather than repeating ideas and techniques: This is what I mean by not making my task easy.

I do not really see myself exclusively as a brass and wind composer, but an all rounder. This I believe helps me a lot as I’m able to deploy writing methods for brass and wind that I might also use for strings or film.

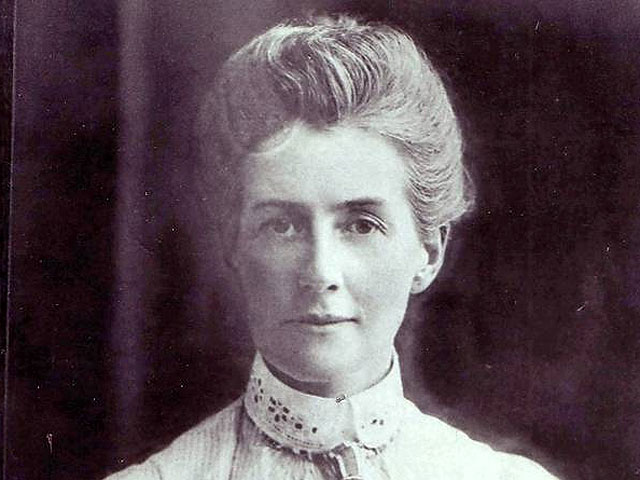

Musical inspiration: Edith Cavell

Chris Thomas: The titles of your works nearly always exhibit strong visual associations, even if they are not strictly programmatic.

Do you find that you need an external stimulus to get you started on a piece or does the music sometimes come before the title?

Nigel Clarke: I spend a lot of time hunting out themes that interest me. For example I’m interested in the First World War nurse Edith Cavell who was executed only about a mile from our family house in Brussels.

I plan to write a work for flugel horn and strings in the coming months on that subject.

'Mysteries of the Horizon’ refers to a series of paintings by René Magritte. I really wanted to write a work that had Belgian blood flowing through its veins, and this subject was perfect for me.

I spent many hours in the Magritte Museum in Brussels and also worked closely with soloist Harmen Vanhoorne and Brassband Buizingen, the band of which he is principal cornet and I’m Associate Composer.

Each of the four movements was named after one of his paintings: ‘The Menaced Assassin’, ‘The Dominion of Light’, ‘The Flavour of Tears’ and ‘The Discovery of Fire’.

In the last few years I’ve collaborated with a British poet and author based in Brussels, Martin Westlake.

This collaboration has been inspiring and I’m delighted that on my recent double disc CD by Brassband Buizingen, each composition is preceded by a poem especially commissioned to go alongside each work.

Most recently I designed my latest wind orchestra work ‘Storm Surge’ to have specially written words by Martin that are read over the music at the beginning of the work. I really feel that has added to the power of the piece.

The premiere was given by the Marinierskapel der Koninklijke Marine (the Marine Band of the Royal Netherlands Navy) under the baton of its Director of Music Peter Kleine Schaars in the De Doelen Concert Hall, Rotterdam.

Working with different genres: With the Royal Netherlands Navy

Chris Thomas: And in these visual associations there is perhaps a direct link to your music for film?

Nigel Clarke: I’m not really sure how true that is, as I’ve always written music around subjects that interest me. I have never been the sort of composer that would write ‘Sonata No 1’ or ‘Theme and Variations’. That just isn’t me.

It might be fair to say that I like to evoke images, ideas and atmospheres when I write.

That surely is no different to Gustav Holst writing ‘The Planets’ or Arthur Honegger’s piece about the journey of a steam locomotive, 'Pacific 231’.

Chis Thomas: How was it that you first become involved in writing film music?

Nigel Clarke: It was really by accident.

A former Principal of the Royal Academy of Music, Sir David Lumsden, recommended me to a producer who was looking for a composer for a film called, ‘Jinnah’ which featured Sir Christopher Lee in the title role.

To cut a very long story short I became part of a film writing partnership with an ex-student of mine, Michael Csanyi-Wills.

We have written over ten feature film scores together, recording several with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and the London Symphony Orchestra as well as other leading symphony orchestras.

Poet, author and collaborator Martin Westlake

Chris Thomas: Where a film score such as your ‘The Little Vampire’ necessitates a very different language to some of your concert music, do you find it natural to genre or style hop and what particular challenges does it present?

Nigel Clarke: As a composer it is an area of writing in which you are a servant to the visual image, often taking on the role of the third actor (an actor you cannot see) in helping to tell the story.

I don’t find this as rewarding as I once did, as you are often asked to write in the language of other film composers, who in turn are also writing in someone else’s style. Consequently, I regard this field as the work of an artisan rather than artist.

There are however always exceptions like Erich Korngold, Bernard Hermann and of course John Williams.

At the end of the day it has been an extreme thrill to record with our country’s finest talents in Abbey Road Studios. But it ‘ain’t art. It’s a highly specialised skill!

In many ways, film music has become a mostly generic language. For that to change it might need a different approach to the music from the director.

Writing film music often means writing short sequences of music where large-scale structure is not imperative to the overall design of the music.

I’m harsh with my judgement of modern film music where sometimes dozens of named and unnamed writers are contributing to the finished product.

I rarely see the inventive qualities of the composer of yesteryear. What I do not understand is why people buy music that is so derivative.

Why not go to the original where real creativity lies?

Chris Thomas: Would you therefore say that the strict discipline necessary for writing for film has had an impact on your wider music generally?

Nigel Clarke: Absolutely:

It’s broadened my musical vocabulary vastly and has also helped give me the ability to deploy ideas from different musical genres at will.

Violinist Peter Sheppard Skaerved

Chris Thomas: Your catalogue includes many works for brass and wind band but it is clear from your collaboration with the violinist Peter Sheppard Skaerved that you have always wanted to remain creatively active across a range of genres.

Was it a conscious decision early on that you didn’t want to risk being stereotyped as a composer active in one particular field?

Nigel Clarke: Working with Peter is a sheer joy and has been the source of my most personal and original music. What I think I am trying to say here is it allows me to be me!

We spend months getting excited about ideas, trying out fragments and then letting the music grow before finally settling on a definitive composition.

We have also been lucky to travel all over the world writing and performing new work, from the Gobi Desert and the Balkans to more locked away and hidden parts of the United States of America.

My work with Peter has never been about performing in famous iconic venues. In fact the opposite is true, taking music to unusual locations where the audience has none of the expectations you would find in more traditional settings.

Another example of this is not performing in concert halls but ‘up close and personal’ in private homes. In fact, the string quartets of the past were often not designed to be played in grand concert halls at all but in much more intimate settings.

My belief is that we should experiment more with musical settings; the results are often surprising.

Working with Peter means that the impossible becomes the possible!!

Relaxing Belgian style with Luc Vertommen and Harmen Vanhoorne

Chris Thomas: Peter Sheppard Skaerved also figures significantly on a Naxos disc of your works that include the wind band piece ‘Samurai’ and ‘The Miraculous Violin’, effectively a concerto for violin and string orchestra.

How specifically has Peter influenced you as a composer since your early days together at the RAM?

Nigel Clarke: I wrote my first larger scale multi-instrumental work for Peter’s (at the time) string orchestra ‘Parnassus’.

In fact, the work was of the same name. We did not collaborate on that work; I simply handed over the composition and attended rehearsals.

These days we spend hours playing with ideas, seeking out musical possibilities and seeing how they can be coloured, using different fingerings, bowings, bow positioning etc.

This approach now infects everything that I do. It has also worked well in my collaboration with conductor Luc Vertommen and Brassband Buizingen.

Chris Thomas: Although there is music for string orchestra in your catalogue, there is nothing for full symphony orchestra.

Is there a reason for this and do you intend to write for symphony orchestra in the future?

Nigel Clarke: If your life style choice is to write for brass band, symphonic winds and occasionally educational music, it probably means you will not be taken seriously as a composer of major concert hall music.

Perhaps this statement should start a debate. Yes, John McCabe, Edward Gregson and Judith Bingham have been able to make that transition but most don’t and the opportunity is probably not open to them.

The same could be said of film music composers where as I mentioned before, the music tends to be quite derivative these days and therefore not in demand in the symphonic concert hall.

4BR Interview: Nigel Clarke - Part 1: http://www.4barsrest.com/articles/2014/1443.asp#.U1Y_pvldUg8