Scheherazade: the eyes of Caligula and the lips of Marilyn Monroe

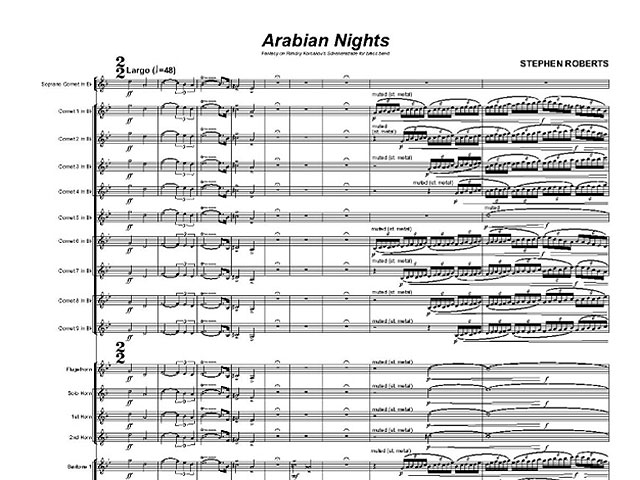

‘Arabian Nights - Fantasy on Rimsky Korsakov’s Scheherazade for Brass Band’

Stephen Roberts has returned to the historical roots of the British Open test piece – although with the addition of some very modern twists to his hybrid Victorian contesting genus along the way.

‘Arabian Nights’ certainly reflects the personality of its creator – and not just Nikolai Rimsky-Korskov, whose 1887 orchestral suite, ‘Scheherazade’, has inspired this thoroughly enjoyable set work.

Roberts’s brass band ‘fantasy’ is a colourfully dry-witted piece of arranging and composing; a fused combination of timeline genres that expertly pays homage to its origins whilst adding a personal vein of modern day virtuosity to the sultry tale of ultimate sexual capriciousness.

Lack

The composer’s musical thought processes are laid out with a welcome straight forward lack of pretentiousness.

“As a test, the fantasy presents a wide variety of moods and character as well as some deliberately written ‘awkward’ passages and tests of stamina, range and control,” he says in his preface to the score.

“Thus the goal is to produce a performance that combines musical personality, exemplary technique and impressive virtuosity!”

The man behind the Arabian Nights - composer and arranger Stephen Roberts

He has already let the bands know what he is looking for, and more pertinently, has also ensured that the most important people at any contest are fully engaged in the musical spectacle that will unfold before them.

Entertained

The paying punters will get to hear tunes they can whistle, cadenzas that will make them draw a sharp intake of breath and climaxes that will bring a shudder down collective spines.

They will leave Symphony Hall thoroughly entertained on a piece that hasn’t required bands to use a computer programme to work out its time signatures.

Isn’t this what brass band contesting, ever since the first British Open in 1853 should have been all about?

It is a return to old fashioned musical contesting challenges.

Left alone

Much like the great arrangements of yesteryear, the composer has left the best known elements alone – using his considerable skill to bring texture and balance to complex musical lines, without losing the essential expressiveness of the original structures.

We therefore get the Sultan in all his misogynistic, mean as a junk yard dog splendour; a man who revels in his spiteful mistrust of the multitude of vestal virgins that end up on his connubial couch each night.

In contrast, Scheherazade is nubile, eloquent and Machiavellian with her wits – an Arabian reminder of Francois Mitterand’s famous remark about Margaret Thatcher; the eyes of Caligula and the lips of Marilyn Monroe.

In between we have Sinbad’s Ship, the Kalendar Prince and Young Princess, the Dervish dancers, a bit of Ali Baba and the forty thieves (who actually don’t appear in any of Scheherazade’s bed time stories), a Bagdad Festival and a rip roaring trip on stormy seas.

Colouristic sections

To these are added what the composer calls ‘colouristic sections’ - tests of individual and ensemble character (fearsome cadenzas and detailed connecting link passages) that fuse together the random highlight themes to give what he calls, “...some extra virtuosity to suit the exigencies of a test piece and the character of the brass band.”

No hidden meanings

On the face of it, it is one of the most straight forward test pieces written for the British Open in many years.

There are no hidden meanings to find – just the best way to tell a great old story.

Yet the performers who underestimate its musical and technical challenges could face an even crueller chop from the three judges than any faced by the poor deflowered virgins that the Sultan sentenced to death after a one night stand.

Take the transparent complexities too lightly and a band could find itself with a one way ticket back to the Grand Shield.

Much to ponder from the start...

Self restraint

There is therefore much to ponder from start to finish with ‘Arabian Nights’.

The opening theme is straightforward enough, but the first linking section requires precision and balance, whilst the opening euphonium cadenza cries out for a sense of self-restraint (it is only marked mf).

Much the same applies to the first sighting of the heroine: quiet, elegant and a more than a little mysterious in the cornet and euphonium duet.

Precise and vibrant

The following orchestral highlights are precise and vibrant, enhanced by the composer’s dry wit (a wheezy soprano line mimics a snake charmer’s pungi, whilst the tubas wobbly like fat bellied dancers) - all bringing extra characterisation to the main solo lines (and ensemble) to bring a sense of personality to the music.

However, despite the different tempo changes and subtle dynamic markings, go too far and the music can quickly descend into parody – a pantomime performance of OTT hamming up.

Capture the perfect pace and it all leads to the cadenzas with a sense of pulsating vigour rather than uncontrollable excitement.

Here is the chance to show off – with the trombone, horns and finally euphoniums leading us into a thrill a minute ride for home – although one that takes some wonderfully realised detours along the way.

Fulcrum

However, the fulcrum of the whole work is yet to come; an extended serenade of such peaceful tranquillity that the old Sultan finally succumbs to Scheherazade’s wily tales (although in the original she has also given him three children by this stage).

It is a test of cultured piano ensemble playing as hard as any found in a test piece, ancient or modern; with a final four bar ending that must (and the composer has emphasised this) be played open.

See no, hear no evil

What will be interesting to see is if the judges back their own aural skills to penalise any bands that employ muted tricks and camouflage.

Let’s just hope they don’t take their own safety first, ‘see no, hear no evil’ option.

Chopping block

With stamina sapping and lips filled with lactic acid there remains a final sprint (although there is a subtle change of tempo to end) topped off with the now infamous top E finish from a soprano, who has to decide in the last few seconds if they really need to put their own heads on the chopping block.

It ends a truly rambunctious tale of Middle Eastern mystery in a fashion that sums up Stephen Roberts’s highly enjoyable work to a tee:

‘Arabian Nights’ demands complete mastery from the competing bands start to finish if the desire for ultimate glory is to end in contesting triumph.

Iwan Fox