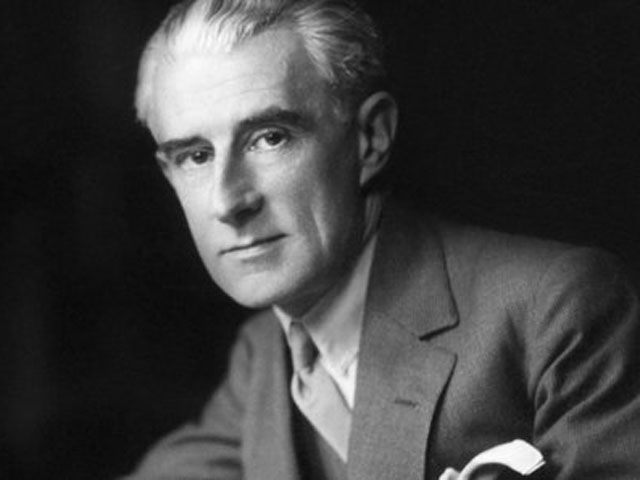

Watch out - it's Maurice Ravel

The great Igor Stravinsky once called Maurice Ravel, a ‘Swiss watchmaker’.

It’s a slightly peculiar epithet for a composer whose genius was to explore the extremes of formal and tonal ambiguity; but in a strange way it succinctly summed up the cool detachment which the Frenchman (his parents were Swiss-Basque) brought to his amazingly precise expressions of perfectionism.

Perfect balance

Much the same could also be said of Howard Snell, whose truly great arrangement of Ravel’s ‘Daphnis & Chloe’ ballet music is the brass band equivalent of a Patek Philippe watch – an almost perfect balance of form, function and aesthetic beauty.

The original ballet was commissioned in 1909 by Serge Diaghilev, with Ravel working on it like a compositional horologist until 1912.

Intriguingly, Stravinsky was at the time writing his own ballet score – ‘The Rite of Spring’, later remarking when a lasting friendship blossomed between the two of them, that Ravel ‘was the only one to understand it’.

Two suites

Unfortunately, their great works are now more appreciated in the concert hall than the theatre – with Ravel’s music split into two orchestral suites – the second of which Howard Snell has brought thrillingly to life with a revised version of his own 1998 original.

The work is really a tone poem in anything else but name – a storyboard (the narrative is a bit weird and wonderful) of vivid characterisation (which borders on the erotic) that tells the tale of two young lovers and their adventures in ancient Greece; the inspiration for which is nicked from a third century pastoral poem.

Much to explore

Much then for the conductors to explore – helped enormously by Snell’s very precise score notes, which not only explain the technical gubbins in forensic detail, but also gives fine advice on the extra curricula homework that will come in handy in the interpretation process too.

Download sales of Pierre Monteux’s recording with the LSO will have turned platinum after his very particular recommendation, whilst more than a few pocket sized French/English dictionaries will have been purchased from WH Smith too.

All in the best possible taste of course...

Daybreak

It opens with ‘Daybreak’ (Lever du Jour) - a sumptuous dawn on the Greek island of Lesbos, heralded by a smooth undercurrent of bass led tonality topped with flickering shafts of speckled sunlight from the soprano and repiano.

Distant echoes of bubbling streams (as distant as the back row cornets can make it) underpin the lyrical bucolic beauty. It’s fragile, sensuous stuff – all about awakenings of all sorts of deep seated kinds.

It’s also immensely detailed; the interlocking elements gearing the forward momentum with subtle delicacy.

Pantomime

The following ‘Pantomime’ is a bit of an early Greek version of an old Whitehall farce – all dropped trousers, mistaken identities, duality and double-entendres.

The original orchestration is at its most brilliant and exotic – yet Snell’s ability to create amazing tonality and texture from a palette a fraction of the size available to Ravel is remarkable.

Differing colours and rhythms

The use of different mutes and instrument combinations bring out the multiple dissonances with razor sharp clarity.

So too the notation, which gives rise to a peculiar rhythmic dislocation, built on precise articulation: Nested triplets (3 within 3), truncated demi-semi quavers and elongated sixes all mix in the miasma to create a spectacular sense of atmosphere and flavour.

Declarations of love, furtive passions, seduction and even attempted rape are played out in kaleidoscopic Technicolor splendour - with some of the most inventive scoring ever arranged for brass band mimicking the original almost to perfection.

Ravel and Snell bring colour to the cheeks of the lovers...

Throbbing conclusion

The ‘Final Dance’ (Danse Generale) is an animated romp that brings the story to a happy ever after conclusion.

It’s pulsating, throbbing even; the blood bubbling in the loins of the protagonists with a passion that will finally be consummated with the visual metaphors of erupting volcanoes and exploding rocket launches very much in the mind’s eye.

Strenuous, strident and completely breathtaking, it pounds towards its climax with an energy borne of rawest of emotion.

It requires an ensemble of virtuosic brilliance with the stamina of a Pamplona bull.

Spent husks

At its close, the finest performances will surely be met with a tsunami of appreciation; the players receiving it like spent husks of lovers drained of their vitality.

Not a bad outcome for a Swiss watchmaker and First World War lorry driver, but a simply fantastic one for a former trumpet player, conductor and occasional boat builder.

Howard Snell’s genius deserves every plaudit that will come its way.

Iwan Fox