2008 National Championships of Great Britain - Test Piece review

7-Oct-2008Paul Hindmarsh takes a close look at the latest testing work from the pen of Kenneth Downie.

Anyone expecting another St. Magnus, Promised Land or Gerontius will be in for a surprise when band number one begins the procession of performances at the Royal Albert Hall on the 13th October.

Anyone expecting another St. Magnus, Promised Land or Gerontius will be in for a surprise when band number one begins the procession of performances at the Royal Albert Hall on the 13th October.

Many of Downie’s larger and more ambitious works have been cast in variation form. It was Variations on Princethorpe and Purcell Variations that in effect ‘made is name’ outside Salvationist circles.

Energy and detail

Concertino is full of characteristic Downie energy and detail, but there isn’t a hymn tune in sight. The score is lean and athletic. There is a great deal of exposed chamber music-like writing – some of it technically challenging – which will present its own problems in the vast ‘open-spaces’ of the Royal Albert Hall acoustic, where performers can feel isolated and precariously ‘audible’. It is a work of ‘abstract’ music.

The forward thrust and dynamism in the writing is the outcome of the composer’s resourcefulness in manipulating his themes and involving all the players in the musical argument, rather than any specific programmatic or narrative content.

Concertino for Brass Band was originally a four-movement Concerto, commissioned by Geo-Pierre Moren and the Swiss band, Treize Etoiles, as an own choice piece for last year’s Swiss National Championship.

Movement dropped

When I asked Ken about the work, he confessed to some disappointment that one movement had to be dropped to fit into the time-scale of the National finals day: "The balance of the work has changed of course, but the opportunity to have a work used at the Royal Albert Hall doesn’t come along every day. Few people have heard the work in its original form, comparatively speaking, so the bands and the audience in London will be coming to it fresh."

To give the opportunity of full performances of the Concerto, the ‘missing’ Scherzo movement is to be published separately under the composer’s own imprint – Kantaramusik. From my reading of the score of the Scherzo, I think it is a great pity that we shall not be hearing it. It's a dynamic looking movement – very challenging, full of energy and cinematic verve and more amply scored than the other movements.

It would have made a contrast to the more rigourously composed outer movements and (in my view) created a more satisfying balance between the amount of slow and fast music in the work. The slow second movement is expansive, while the rapid moto perpetuo finale is very compact.

Different compositional approach

The three movement of the Concertino are very different in compositional approach. The opening Allegro is the most highly organised of the three and the most detailed in its fragmentary writing. I was interested to read in Ken’s note that he acknowledged a debt to Wilfred Heaton’s ‘wonderful creative methods’ in this movement: ‘ Contest Music hovers around the movement.

He told 4BR: "I often get seduced by those big, rich and sumptuous sounds on the band, but here I was trying to be more sparse and concentrated – working my themes to the full in the way that our great friend did in his music. "

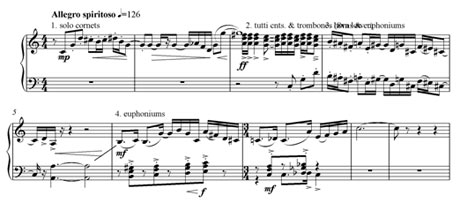

The first movement of Contest Music relies on the juxtaposition and development of a number of short, memorable and contrasting musical motifs. With due deference to Heaton, everything is derived from a series of short ideas which he sets out in one after the other as an opening gesture (to letter A in the score). As Ken told me: ‘Developing them was fun. ‘

Different element

Each motif has a different element for the listener/ player to catch hold of and trace through the movement:

1. A playful idea of the rising fifths and sharpened intervals of the first (You are not sure what the key is here);

2. A forthright sequence of fanfare triads for the second one;

3. A slippery chromatic falling theme;

4. A little tune with wide intervals and arpeggios

After displaying his ingredients, Ken then proceeds to create his recipe. His intention was for each idea to be distinct and memorable, so that their progress and interaction can be followed as they get passed round the band in a sort of evolving mosaic.

State of flux

The themes are in a constant state of flux – he sets out on developing them right away – and he hasn’t followed the conventions of sonata form (as Heaton did) in order to give the movement coherence and structure. So it will be very much up to the conductors and bands to grasp and convey the ebb and flow of the argument, as the various episodes unfold.

For example, just after rehearsal mark D, the flugel horn seems to herald a new developmental episode , where Ken turns his main theme upside down and transforms it into a short breath of wide-ranging melody.

And then this gets passed round the band and leads to the central climax of the movement, where the principle theme sounds out on the full band. Following that there is a section which concentrates on the chromatic third motif in contrapuntal and dramatic style.

There’s also a feeling of recapitulation later on (from bar 113). As Ken conceded: " Although I wasn’t consciously trying to construct a movement in sonata form, the classical shapes are there in the background."

At the end, as the music dies down, the main ideas come back in reverse or inversion, so that the movement’s musical arch has an elegant symmetry about it.

Restless energy

The overall effect of this movement is one of restless energy ( to my inner ear – not having heard it played yet!). While most of the players are involved in the musical argument at some point, no one gets to say their piece for very long. There is much for the conductor and musicians to do by way of binding the often fragmentary textures into a satisfying whole.

Ken’s admiration for the formal elegance and musical symmetries of the first movement of Contest Music is clearly evident:: "That movement is highly organic and woven together. It’s just brilliant. I Wilfred saying to me that he couldn’t always pin down how much of the creative process was totally conscious and how much just happened. Sometimes you are not even aware of what you have done until someone like you points it out. Things seems to take on a life of their own!"

Concious

However, much of the working out in the Concertino is completely conscious.

For example, the opening phrase of the slow movement is loosely connected to the opening themes of the first. The slow movement is in a free, lyrical form, with three paragraphs that present contrasting ideas. There are two elements to the first paragraph, forming a little A-B-A shape.

Although marked Lento espress, the little melodic fragments that get passed round the band will need to maintain a sense of growth. Over indulgence of the expressive moment will impede the organic flow of the harmonies. The second episode is more hymn-like in character, beginning on bass trombone and third cornet!

As Ken observed: " When you’re writing for a competition and you want to keep everyone interested!"

Notable lack

In fact the work is notable for a lack of solo moments for the principal players.

This work was not composed as a set test piece and thus the composer was not tempted to halt the progress of his music by including set-piece solos or cadenzas. This is a Concerto/Concertino for the whole band, and in that sense it ‘doffs its cap’ in the direction of celebrated works like the Concertos for Orchestra by Bartok, Kodaly or Lutoslawski in giving everyone a moment in the spotlight.

The melody of the third section (at letter O) is given to the whole solo cornet section in ‘conversation’ with euphoniums and then trombones.

Adjudicators will be listing for the ideal beauty, balance and blend of tone here. After that (at letter P), in the most extended ‘solo’ moment of the whole work, the principal cornet and euphonium are heard in duet: Ken says: "I had in mind here the kind of thing that Shostakovich did in his Fifth Symphony where flute and solo horn engage in a lyrical duet with wide leaps in the melody."

There is a lovely, restrained character about this movement – the loudest dynamic is mezzo forte – and it includes those subtle shifts of harmony and colour that I and countless others so enjoy Ken’s hymn-tune settings.

Urgency

The running semi-quavers and stabbing chords of the fast and furious rondo-finale present a very different kind of challenge. In the ample Albert hall acoustic, clarity and precision will be essential at the speed the Ken demands. And he does not expect this high-energy tempo to yield until the final pages: "‘I am hoping that a sense of urgency is maintained right up to the coda, with the opening idea acting as a refrain binding it all together."

Anoraks

And for the anoraks, I’m grateful to John Ward (of the British Bandsman and repiano player with Desford) for pointing out a Downie musical joke that Wilfred Heaton would have been proud of.

At bars 20 Ken has sneaked in a quotation from an old Salvation Army song, In the strength of the King. The words of the quote are ‘We’re a band that shall conquer the foe’! . The chorus, which I remember singing many times as a kid in the SA is, ‘I believe we shall win if we fight in the strength of the King’.

Big finish

The Concertino has the kind of big finish that writers brought up in the Salvation Army are particularly good at. Ray Steadman-Allen and Leslie Condon are masters of the elaborate hymn-tune finish (Think of The Holy War or The Call of the Righteous) Others like Ken have taken on that mantle and even the finish of Edward Gregson’s latest work, Rococo Variations, has something of the same spirit lurking in the background.

Here in the Concertino’s concluding peroration, Ken reprises the main theme from the first movement.

To my ear it follows naturally, because all the themes he has used to share a family likeness: Ken adds: "And because the running semi-quavers underpin everything anyway, I am hoping that this will provide a degree of continuity and logic for the listeners and players. I am certainly expecting the best bands to provide a terrific wall of sound at the end."

Different concept

Ken is aware that the Concertino (even in its truncated form ) is very different in concept and character from his other recent big pieces:

"People are always ready to categorise you, but I don’t think that the brass band audience has heard all the sides of me yet. I’m looking forward to writing a lot more and, yes, there will be surprises for people along the way. It is easy for players to fasten on to a few things and it’s comfortable for listeners to pin labels to you, but I hope all involved at the Royal Albert Hall next month will approach my work with open minds."

Paul Hindmarsh