Although it is a matter of debate to exactly when the ‘modern’ brass band took full fledged form in metamorphosing from its embryonic beginnings into the mature body we recognise today, the mid to late Victorian era certainly encompassed its fundamental change.

The fusion of mass production processes, financial, social and cultural elements brought structure and uniformity – bringing together emerging, if haphazard strands into a fully identifiable and ultimately standardised body of music making.

By the 1850s the idiosyncrasies of the serpent, clavicorn, bass horn and keyed bugle were on the point of obsoletion, the ophicleide soon to be surpassed by the advent of the bass saxhorn - the euphonium.

At the great ‘National’ brass band contest of 1860 the writing was on wall. The ‘Best Ophicleide’ player from the Cyfarthfa Band was presented with a brand new euphonium for his efforts.

Musical coelacanth

Today, the keyed bugles and rudimentary saxhorns are still performed on by the likes of the Wallace Collection – reanimated from their entombed amber stasis like the revived dinosaurs of ‘Jurassic Park’.

Only the ophicleide survives – a musical coelacanth; a living fossil to be found swimming in occasional orchestral waters.

Only the ophicleide survives – a musical coelacanth; a living fossil to be found swimming in occasional orchestral waters.

The cornet, dominant by the late 1840s, became the ubiquitous virtuoso instrument – and in the hands of the finest players its scope for tonal melodic expression was matched by its facile technical security.

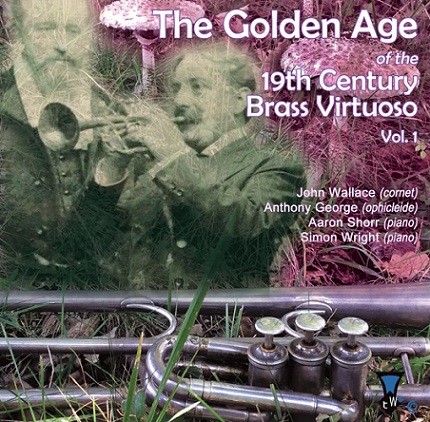

Musicality met ingenuity in almost perfect form – its popularity secured by legendary players performing solos of wide ranging invention and dexterity. And, as John Wallace’s splendidly intuitive renditions shows (on an 1862 Bayley Acoustic model), the reasons are obvious.

He steps back in time with such ease of stylistic understanding and artistry you could be forgiven for thinking he did the recording in a frock coat and Isambard Kingdom Brunel stove pipe top hat.

Restored genius

As for the ophicleide – we can only revel in the present day artistry.

Anthony George is a splendid exponent of a lineage that reaches back to the great Sam Hughes, who performed with the Cyfarthfa Band and by the mid 1850s was a member of the Royal Italian Opera Orchestra.

However, unlike John Hartmann and Alex Owen whose names still hold resonance today, Hughes died in impoverished obscurity in 1898.

Anthony George is a splendid exponent of a lineage that reaches back to the great Sam Hughes, who performed with the Cyfarthfa Band and by the mid 1850s was a member of the Royal Italian Opera Orchestra.

It was his misfortune to become arguably the greatest player of his generation at a time when the instrument reached its pinnacle of design, but had passed its peak in popularity. George’s operatic rendition of ‘O Ruddier than the Cherry’ (Hughes’ showpiece) pays a wonderful homage in restoring his genius.

In fact everyone associated with this 2015 project (recorded in a Victorian hall with accompanists playing on an 1844 piano) does the same.

Iwan Fox

To purchase: https://thewallacecollection.world/portfolio/twcfr2020003-gav1-cd/

Play list:

1. Zerlina Polka (Émile Ettling)

Wallace/Wright

2. Scene et Bolero op. 288 (Joseph Labitzky)

George/Shorr

3. Grand Fantasia Alexis (John Hartmann)

Wallace/Wright

4. The Death of Nelson (John Braham)

George/Shorr

5. Souvenir de la Suisse Polka (Alessandro Liberati)

Wallace/Wright

6. O Ruddier than the Cherry (George Frideric Handel)

George/Wright

7. Goodbye Sweetheart, Goodbye (Alexander Owen)

Wallace/Wright

8. Incidental Music for Macbeth (Matthew Locke)

George/Wright

9. Sweet Spirit Hear My Prayer (William Weide)

Wallace/Wright

10. The Watch on the Rhine (John Hartmann)

Wallace/Wright