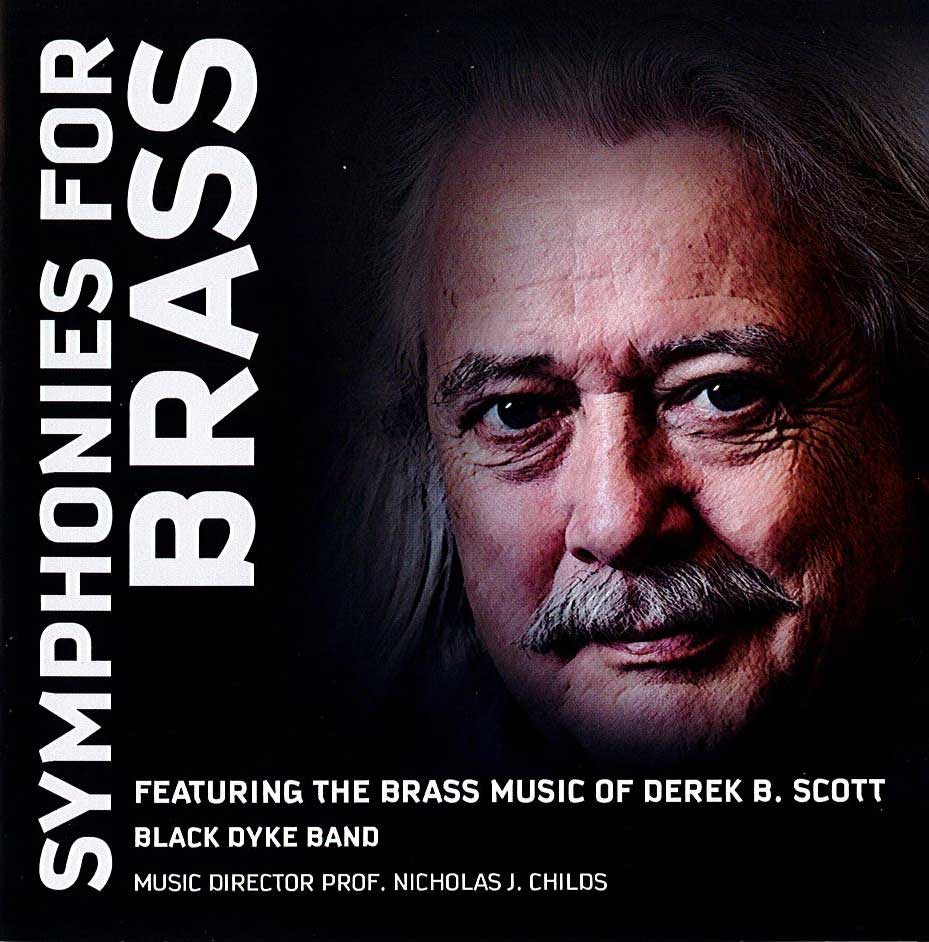

You can almost be guaranteed that an academic with a PhD in the sociology and aesthetics of music, who has composed a concerto for the Highland bagpipes and written a book entitled ‘From the Erotic to the Demonic’, would come up with compositions for the brass band medium that are a bit different from the norm.

That is certainly the case with Derek B. Scott.

He was appointed Professor of Critical Musicology at the University of Leeds in 2006, although the works featured on this release precede that appointment - four of the five written when he held the same position at the University of Salford.

It’s not clear if he intends to write for brass bands again, but it would be a great pity if he wasn’t persuaded: We could certainly do with more voices with his particular, and at times, peculiar stamp of individuality; the academic rigour laced with acerbic observation.

Case in point

The quirky ‘Wilberforce March’ (Op.10a) stretching as far back as 1978 is a case in point.

Taken from his operetta inspired by the life and work of the anti-slavery pioneer and the subsequent Abolition of Slavery Act in 1833, it’s a compact amuse-bouch with a bittersweet aftertaste; the transparent style, with its brace of related but divergent contrasting themes, underpinned by a deeply serious message of intent.

A much lighter form of professorial cleverness is to be found in ‘Perpetuum Mobile’ (Op. 29) - the type of musical retirement present given to colleagues who really wouldn’t appreciate a carriage clock to while away the hours of new found leisure.

Meanwhile, ‘Dafydd y Garreg Wen’ - originally for voice, but later for brass band, is a death bed fantasia whose melancholic undercurrents are turned into a triumphant acclamation that wouldn’t have been out of place being sung at Cardiff Arms Park; the terminally ill ‘David of the White Rock’ rousing himself for one last chorus before joining the tenor section of great ‘Choir Invisible’ in the heavens.

Meanwhile, ‘Dafydd y Garreg Wen’ - originally for voice, but later for brass band, is a death bed fantasia whose melancholic undercurrents are turned into a triumphant acclamation that wouldn’t have been out of place being sung at Cardiff Arms Park; the terminally ill ‘David of the White Rock’ rousing himself for one last chorus before joining the tenor section of great ‘Choir Invisible’ in the heavens.

Symphonies

It is however the two contrasting symphonies that offers an intriguing insight into his structural approach to the medium.

‘Symphony No 1’ (written in 1995) is derived from seemingly fragmentary material moulded with an intuitive feel for different genres (reflecting in many ways the breadth of his academic research) - from the contrasting dialogue observed in the opening ‘Allegro Moderato’ and ‘Adagio’ to a waspish ‘Scherzo’ and a fluid, minor-keyed finale that grows in complex intensity.

The step between that and ‘Symphony No 2’ written in 1997 is as substantial as it is diverse; the work much more richly developed in tonality and technical complexity, linked to 18th century symphonic form but given an inventive twist with its motifs and material inspired directly or indirectly from conflicting tensions - from the picturesque and bucolic to the ferocious and spiteful.

You are left wondering what developments he would have explored with a third outing.

Hopefully he can be persuaded to allow us to find out.

Iwan Fox

To purchase: https://www.blackdykeshop.co.uk/symphonies-for-brass---the-music-of-derek-scott-229-p.asp

Play list:

1. Wilberforce March (Op. 10a)

2-5. Symphony No 1 for Brass and Percussion (Op. 23)

6. Dafydd y Garreg Wen (Op. 25)

7. Perpetuum Mobile (Op. 29)

8-11. Symphony No 2 for Brass and Percussion (Op. 26)