A statue of greatness: The Mortimer Trophy presented to the winning conductor

Dynastic history is universally commemorated in stone not sound.

Statues, busts and sculptures perched on top of plinths and granite columns, bronze cartouche engravings recording lists of battles won and honours gained. They are the public almanacs of achievement, displays of pride as well as propaganda.

They tell us everything we are supposed to know, yet the emotions they elicit are invariably distant, lifeless and even false.

If only we could hear how that history was actually made.

Black ink

With Peter Graham’s British Open test-piece, perhaps we can: His musical commemoration of the Mortimer family replaces the chiselled gold lettering of genealogy with the black ink of brass band scoring.

No stone edifice could ever recapture the immediate emotions seared into the memory banks of those lucky enough to have heard the great Foden’s Band of the 1930s; ‘Kings of the Earth’ as they were called, playing music that ‘flowed like oil’, sonorous and refined under Fred Mortimer’s magical, if aesthetically idiosyncratic direction.

And then there was Harry; performing gossamer-light cornet solos with a sound “like an orchestral instrument – a violin, an oboe”; a player, who according to one contemporary “could get more music from a single crotchet than anyone I ever heard.”

No stone edifice could ever recapture the immediate emotions seared into the memory banks of those lucky enough to have heard the great Foden’s Band of the 1930s; ‘Kings of the Earth’ as they were called, playing music that ‘flowed like oil’, sonorous and refined under Fred Mortimer’s magical, if aesthetically idiosyncratic direction.

Carved in tonality

‘Dynasty’ is therefore a composition carved unmistakably and very deliberately in tonality, texture and shaded colour; evocative, affectionate and all together full of life.

Hard edges are replaced by soft chamfers, dynamic excess by considered volume and effect (there are only a handful of fortissimos in the whole piece and the percussion writing never dominates), needless technique by artistic refinement.

His is a subtle, perceptive aural monument to greatness.

Monument man: The composer:Peter Graham

Elegiac memories

It is a symphonic tone poem that resurrects elegiac memories both first and second hand; ones that will be readily identifiable to the rapidly diminishing ranks of those who actually heard the Mortimers in performance as to those who have since sought out their fragile shellac recordings.

The tonal inspiration – the very heart of Graham’s structure - comes from the dynasty’s most famous son – Harry (1902-1992); the prodigy turned dues ex machina

The tonal inspiration – the very heart of Graham’s structure - comes from the dynasty’s most famous son – Harry (1902-1992); the prodigy turned dues ex machina; a man crafted in musical artistry (even the chapter headings of his autobiography came from Handel’s ‘Messiah’) - the most elegant talent of his or any other banding age.

His was a golden sound that shimmered with intensity, his phrasing a thing of cultured understanding and purity.

Dues ex machina: Harry Mortimer in his playing prime

Shadow

Even his father Fred (1879-1953) ultimately stood in his shadow; so too his brothers, Alex (1905 - 1976) and Rex (1911-1999) – although each wrote their own chapters (some almost as substantive and at times as vivid) in the historical family ledger.

The chronological threads that weave the pages of Peter Graham’s composition together are sympathetically bound into seven linked sections.

They are expertly crafted in a cyclical Lisztian tone poem form of reflective pictorial mood and recall, from first entry (a four note leitmotif reminiscent of the solo ‘My Treasure’) to the ‘Messiah’ fugue and ‘Severn Suite’ climax to end.

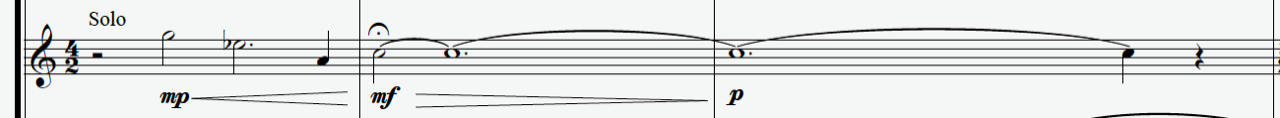

‘as if descending from the heavens': The opening to 'Dynasty' on the principal cornet

Artistic destiny

The opening (‘Harry’), sets the time-line in motion.

It gives us the emerging sense of artistic destiny led by the solo cornet, the quasi cadenza subtle in its demands as the founding father moulded the son’s God given gifts (‘as if descending from the heavens’) through music such as Flotow’s opera ‘Martha’ - a touchstone that intuitively informed the creative beauty of his playing.

The vine of musicality: Flotow's opera 'Martha'.

Haunting

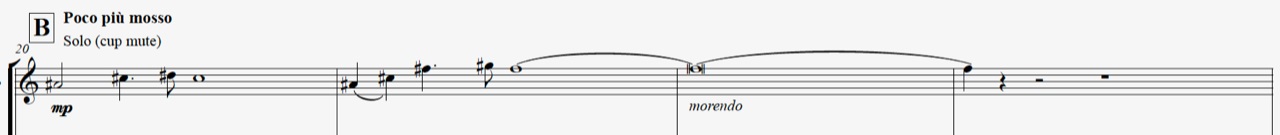

It is followed by the patriotism of misplaced First World War optimism (the haunting whistling of ‘A Long Way to Tipperary’) as Fred goes to France in 1914 - the horrors soon to engulf him with a mechanic brutality at such odds with his own musical ambitions.

Wartime optimism comes with the haunting whistling of ‘A Long Way to Tipperary’

The interregnum that followed was filled with a deliberate forgetfulness (for a time at least) - the music recalling Harry’s stint learning his craft in local theatres playing along to silent movies and variety hall acts, the music free-wheeling and exciting, yet still underpinned by a sense of serious artistic merit (he joined the Halle Orchestra in 1927).

Peak of conquest

During the second decade of this period the Mortimers’ reached their peak of conquest; Fred leading a Foden’s Band without parallel to a double hat-trick ‘Journey’ of success at the National Championships (he would not allow his band to battle against the proletarian pleasure sounds of the Belle Vue fun fair attractions) with playing that combined brilliance with beauty - not over-stated or overblown - the epitome of cultured muscularity; lean, lithe and endlessly adroit.

This was the ‘Golden Age’ of the Mortimer family – father conducting sons ‘Together’ on ‘Severn Suite’ to their first success together in 1930 – six more to follow soon after.

This was the ‘Golden Age’ of the Mortimer family – father conducting sons ‘Together’ on ‘Severn Suite’ to their first success together in 1930 – six more to follow soon after.

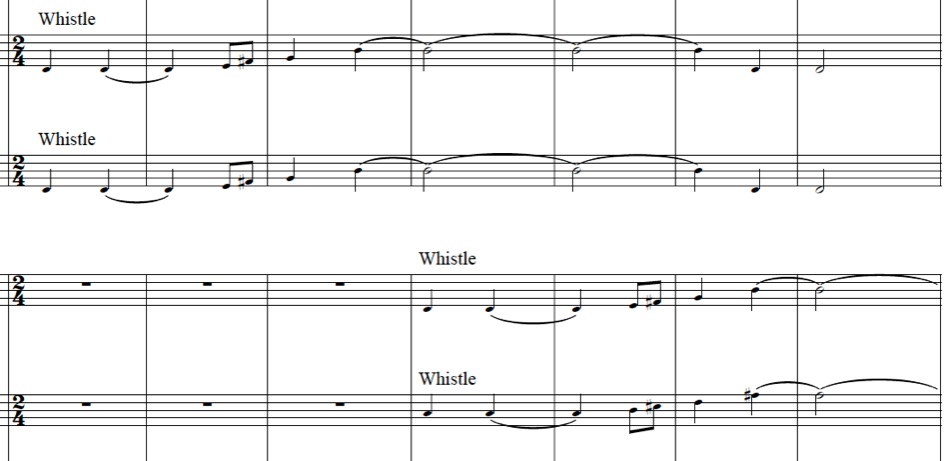

Here Peter Graham cleverly intertwines fact and fiction very much of his own – using an excerpt from Jack Beaver’s ‘Sovereign Heritage’ as a quartet cadenza mechanism (Foden’s won on the piece at the Nationals in 1954, the young composer hearing it on his first trip to Belle Vue for the British Open in 1972) to play out a fantasy of history of his own.

A Sovereign touch - part of the quartet work for solo cornet and repiano

End of an era

‘Farewell’ marks the end of the era with Fred Mortimer’s death in 1953.

A tender homage to ‘Severn Suite’ forms the cortege music drawing the music forward (and it is music that the composer has deliberately written not to become bogged down in over-sentimentality or saccharin coated artifice).

Fred Mortimer with his favourite trophy...

Echo

Harry, Alex and Rex had already set out on new lives for themselves – ones that were at times quite distant from each other (also listen out for the tiny echoing fragment of the most famous of cornet solos – like a last goodbye).

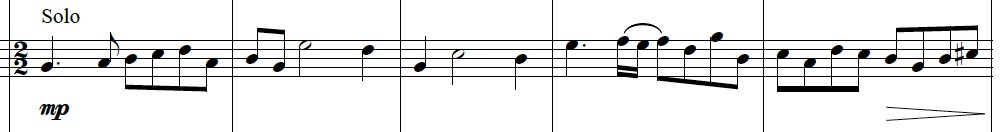

The work could close in no other way than to quote freely from Handel’s ‘Messiah’ – the music that more than any other informed Harry’s appreciation of artistic beauty (he finally got to conduct it with massed brass bands and choral society late in his life).

A fugal ‘Amen’ of finesse led by the Eb tuba builds in intensity (but with controlled dynamics and acceleration) to the inverted touch of majestic ‘Martha’.

The opening to the fugue - played by the Eb tuba..

Noble recall

The noble recall of ‘Severn Suite’ (played at a single forte that shimmers with intensity) leads into a final homage - although of a different kind (one that offers more than a nod to Harry’s entrepreneurial spirit of adventure as the driving force behind the post war British Open) and a hint of Gilbert Vinter’s ‘John O’Gaunt’ leading into a glorious Allagando apotheosis.

‘Dynasty’ is a work that has already surprised many, and will surely do the same at Symphony Hall.

In a test piece era of brittle edged bombast, corpulent excess and self indulgent emotion it is a pertinent and expertly crafted reminder of what history will always record as the greatest achievement of any brass band - that of the timeless beauty of its sound.

Iwan Fox