4BR Time Team - Wingates Band and the Pretoria Pit disaster

5-Nov-20104BR recalls the story of one of the worst pit disasters in history, and how it almost destroyed one of the most famous bands of the Edwardian era - Wingates Temperance.

1910/2010: A centenary commemoration

Centenary anniversaries are not always occasions for great celebration in the banding movement: They are also dates for sombre commemoration too.

The 21st December this year is one such date.

Explosion

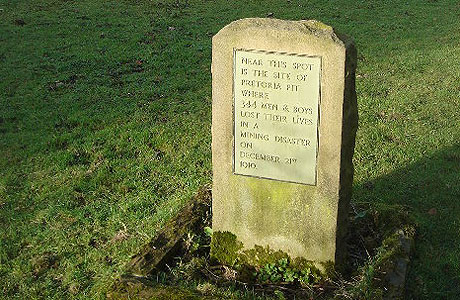

In the metronomic passing of a few seconds of time as the clocks in the mining cottages of Westhoughton ticked past 7.50am on a Winter morning in 1910, 344 men and boys lost their lives to a massive explosion deep in the bowels of the local Pretoria coal mine.

It was to become the third worst disaster in British mining history – a black edged obituary notice in a remembrance book of mourning headed only by the catastrophes of Senghennydd in South Wales and Oaks Colliery in Barnsley.

Until that fateful day, the South Lancashire town was famous as the home of perhaps the finest brass band of the first decade of the 20th century – Wingates Temperance.

Double champions

Founded in 1873, they had created history in 1906 and 1907 by becoming the first ‘Double Double’ National and British Open Champion under the direction of the great William Rimmer.

At the time of the disaster they were still one of the leading bands in the country, although a number of the ‘Double’ players had left to join rivals such as Horwich Old, whilst Rimmer himself had retired from conducting all together.

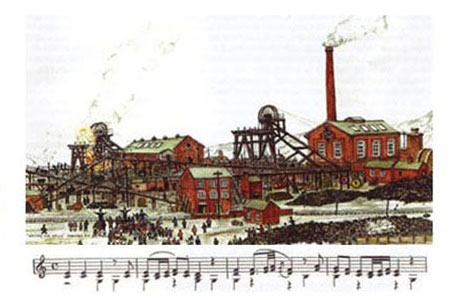

Wingates Temperance Band: 1907 Double Double Champions

Of those who played in the 1907 Belle Vue winning contest, only 8, according to the official September Contest player list were still with Wingates three years later.

However, led by the equally great Alexander Owen they had just won 4th prize at the 1910 September Belle Vue event, and according to historical records, were still winning prize money to the tune of £1,440 and 12 shillings in 1907 alone, and playing to audiences of over 50,000 on their annual tours to Scotland. .

Livelihoods

Buoyant, confident, financially sound (they owned their own bandroom), the band that met for rehearsal on the night of the 20th December 1910 comprised a significant number of players whose livelihood was linked to the Pretoria Pit, which had opened for full production in 1903.

All that changed in the crepuscular darkness that fateful following morning: 889 men and boys comprised the day shift workforce that day – now 344 of them were dead.

By the time the dust had settled amid the remnants of broken bodies and anguished cries of fear, at least seven band members had lost their lives, with possibly a further five associated with the band amongst the victims.

Such was the scale of the disaster they were still exhuming bodies from the pit three months later.

Wingates Victims

The seven confirmed band victims were:

William Cowburn, aged 40; Band Chairman and Bb bass player, who left a widow and seven children. His eldest son aged 16 died in the explosion too.

Albert Lonsdale, aged 37; Secretary and soprano cornet player, who left a widow and seven children.

Samuel Farrimond, aged 37; Eb bass, who left a widow and three children. His brother and son also died in the disaster.

Thomas Farrimond, aged 40; Librarian and percussionist, who left a widow and seven children.

Fountain Byers, aged 33; A former member, playing with Horwich Old Band at the time of the disaster. He left a widow and a son aged 7.

John Bullough, aged 55; A founder member of the Wingates Band and a former euphonium player. He left a widow and daughter aged 16.

Edward Halliwell Green, aged 22; Repiano cornet player and unmarried.

It is also believed but not confirmed that five other men; Jesse Chadwick, Thomas Smith, Richard Jolley, Joseph Hilton and Isaac Ratcliffe – who had at some time prior to the disaster been associated in some capacity with the Wingates Temperance Band, also lost their lives.

Deeply personal

Details of their deaths are heart rendering – and deeply personal in their intimacy.

Albert Lonsdale’s wife identified his body only by the unusual shape of his fingernails; Fountain Byers fought against horrendous burns for a whole day – his dying words to his wife – ‘Jesu, lover of my soul’. He was buried on Christmas Day.

The body of Thomas Farrimond was the last to recovered from the pit the following February.

As was the case in the mining industry of the Edwardian era, the families were left with next to nothing to survive on; Thomas Farrimond’s widow Alice and seven children had to live on the equivalent of a 65p allowance per week.

However, the men's musical contribution to the Wingates Temperance Band was commemorated.

The headstone of Albert Lonsdale featured an engraved cornet; that of Thomas Farrimond, a bass drum.

The Pretoria Pit and the Dead March from Handel's Saul

The aftermath of the disaster saw the Pretoria Pit resume full production as early as the following January, although the band took a considerably longer time to recover its former position of strength.

Remarkably, they played hymns at numerous funerals in the weeks that followed –‘The Dead March’ from Handel’s ‘Saul’ performed to the sound of muffled drums as the remaining players wore black arm bands out of respect to their colleagues.

Recovery

Slowly but surely Wingates Temperance recovered, and by the following summer of 1911 they were performing local concerts, and although they did not perform at the September Belle Vue contest, a few weeks later under Owen’s direction they came 3rd at the National Finals at Crystal Palace.

Although never again the all conquering force they were before the disaster, they still won at Belle Vue in 1918 (under J.A Greenwood), ironically thanks to the fact that they were able to compete throughout the First World War due to the ‘reserved occupation’ status of the mining industry – although the pits of the era were no less hazardous than the Western Front.

The final resting place: All that remains of the Pretoria Pit

According to the player list from that 1918 event, no less than 8 Wingates players were members of the band that performed at the same contest just weeks before the 1910 disaster.

What thoughts must have crossed their minds in victory that day?

2010 commemoration

Further Belle Vue victories came in 1921 and 1923, although the National title eluded them until 1931.

And despite further success in the decades that followed, that mark of history from the 21st December 1910 remains with the band to this day.

100 years after the Pretoria Pit disaster the lives of the 344 miners will be commemorated by a special concert in the town on Saturday 20th November, where the Wingates Band will launch their new CD entitled, ‘Perspectives of Pretoria’, featuring a new commission from the pen of Lucy Pankhurst called, ‘In Pitch Black’.

This emotive, atmospheric work relates the story of the immediate aftermath of the explosion; terrifying and claustrophobic to start, before gaining reference through the lasting tragedies of loss and mourning, to the finally realisation that hopefulness remains despite the sacrifice made.

A century after the horrific disaster left its indelible imprint, a community and its band, will remember.

Iwan Fox