The Musical Brain - Part 2 - When Things Go Wrong

6-Dec-2009In the second part of his exploration of the musical brain, Chris Davies looks at some of the more complex issues which arise when things go wrong.

Opening the door to the Musical Brain....

Picture courtesy of Simon Bosch

http://www.digital-illustration.com.au/fsetcont.html

For those of you who read my previous article, ‘The Musical Brain: A Brief Introduction’, you should be fairly familiar with the complexity of the human brain’s musical abilities.

You should also be familiar with some of the ways in which the normal human brain operates when we are performing music-related tasks. Not all of us, however, possess a ‘normal’ brain, and this can have massive repercussions for musical abilities.

Damage

Some people suffer brain damage due to severe trauma (like head injuries sustained during a car crash), while others suffer from lesions.

Some people are born with specific brain defects, while others develop music-related problems in tandem with other conditions, like dementia or strokes.

It is often very difficult to pinpoint exactly which part of the brain has been damaged by a stroke or other trauma, because, as I mentioned last time, musical abilities are widely distributed throughout the human brain, with multiple areas involved in a single musical process.

What I hope to do in this article is give you a brief overview of some of the most fascinating conditions in which musical abilities are profoundly affected, whether positively or negatively.

Rain Man - Kim Peek

Savants and Rainmen

A ‘savant’ is someone who suffers from severe mental disabilities yet displays brilliance in at least one particular area. Kim Peek (above), the original ‘Rain Man’, is a savant, yet he is not autistic.

Despite his lack of social development, Kim is known for his calendar-calculating ability, whereby he is able to identify the exact day that fits with any calendar date in the past, but also for his stunning memory.

He is able to retain vast amounts of information from every single book he reads (practically the whole thing), and is able to finish reading each book exceptionally quickly.

He is able to read the left page with his left eye and the right page with his right eye (taking in far more information than the rest of us), and this usually takes no longer than 10 seconds a page.

Stunning abilities

Despite these stunning abilities, he has severe motor problems, and struggles to button up his own shirts. One of the reasons for Kim’s strange combination of brilliance and low IQ is the fact that he was born without a corpus callosum (the bundle of nerves that joins the two sides of the brain together).

This seems to have resulted in a vastly increased memory capacity.

Musical Savants

Although Kim Peek is a savant, he is not a musical savant. Musical savants, like general savants, have severe social deficits and a low IQ, yet have an array of outstanding musical abilities that would challenge even those of the finest musicians.

Musical savants are usually male and are often blind, and they display a truly enviable selection of skills, including perfect pitch and an extensive musical memory . Savants are usually able to play a piece of music by ear after a single hearing, and are often able to recall pieces of music after several years, without hearing it in between.

Although it is unclear exactly what causes savant syndrome, what is known is that it is associated with some kind of damage to the left brain.

During our time inside our mothers’ wombs, the two hemispheres of our brains develop at different paces, with the left hemisphere developing over a longer period than the right.

As a result of this, the left hemisphere is slightly more susceptible to damage than the right, and can often be overpowered by the more developed right hemisphere.

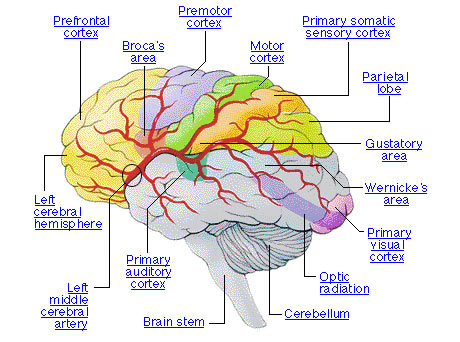

Brain mapping: What's what...

If the left hemisphere fails to develop as it should, the faculties of the right hemisphere are able to dominate. As I mentioned last time, the left hemisphere is the seat of language, and, if inhibited and underdeveloped, will be unable to provide the level of language function that you or I enjoy.

For such individuals, language skills will tend to develop in the right hemisphere, which, although still capable of linguistic abilities, is simply not as good at them.

Similarly, the increased activity of the right hemisphere brings with it advanced abilities in pitch discrimination and musical imagery, including perfect pitch and astonishing musical memory.

Uncontrolled

Although musical savants have excellent musical ears and memories, they are severely destitute in other musical areas. Savant pianists for example will often play the piano with their heads lent back, and they never suffer from performance anxiety.

Their social limitations mean that they are unable to understand the social factors involved in concert performance. Musical savants also tend to have a poor sense of rhythm (which is controlled more by left-brain structures than right-brain ones).

That savants also have very poor coordination, and often display uncontrolled movements down the right side of their bodies implies that damage to the left hemisphere of the brain may be responsible.

Blind Tom

One particularly famous musical savant is Blind Tom Wiggins (below), an African-American savant pianist born in 1849. Although he had an excellent musical memory and learned probably more than 7,000 pieces of music, his vocabulary was severely stunted, at around 100 words.

A regular part of his performances was ‘the challenge’, where he would reproduce brand new compositions in front of an audience by ear, to prove that his outstanding memory was not a trick.

Blind Tom Wiggins

Musical Fits

One particularly weird and wonderful case is that of ‘musicogenic epilepsy’. This is exactly what it sounds like – seizures induced by simply listening to the right combination of musical parameters.

Classified in 1937 by Macdonald Critchley, musicogenic epilepsy is a rare condition, yet several cases have since been documented in the medical profession.

In his recent book, Musicophilia, neurologist Oliver Sacks (below) reports the case of ‘Silvia N’, a lady who developed a strange seizure condition during her early thirties . She was unable to listen to her favourite music, Neapolitan songs, because they induced seizures.

These seizures were often of the ‘grand mal’ type, which involves losing consciousness and having convulsions. Her condition was so debilitating that she underwent brain surgery to correct it, and now enjoys her music without fear. Imagine not being able to listen to your favourite music for fear of having a massive fit!

Amusia

‘Amusia’, put simply, is a lack of music. We’ve all met people who claim to be ‘tone-deaf’ or ‘completely unmusical’, but we probably never thought anything of it. Recent research has shown that there is in fact a neurological condition that renders the sufferer musically destitute; in other words, their so-called ‘tone-deafness’ may be caused by neurological factors.

Amusia, as this condition has been labelled, can be either congenital (something you’re born with) or acquired (something you pick up later on, often as a result of severe head trauma).

It can be split up into 2 broad categories: ‘expressive amusia’ refers to problems when it comes to playing or reproducing music, whereas ‘receptive amusia’ refers to problems in understanding and processing music.

It’s often hard to investigate potential cases of amusia, because it is usually accompanied by other deficits (particularly language deficits – you might recall the links between music and language I discussed in my last article).

‘It all sounds like screaming to me!’

Although amusia is a pretty broad term, scientists are beginning to realise that there are many different kinds of ‘amusical’ behaviour. Some people, for example, lose their rhythmic abilities but keep their sense of pitch (and vice-versa), while others fail to hear music as music per se, hearing noise instead.

Oliver Sachs

Oliver Sacks has found a particularly interesting case of the latter in a patient he refers to as ‘Mrs. L’. She claims that she has never heard ‘music’, and, oddly, compares her experience of what the rest of us identify as music to listening to pots and pans being thrown around a kitchen .

Mrs. L is completely unable to tell whether one pitch is higher or lower than another one, and could only ever learn to play easy pieces at the piano by learning finger patterns. Interestingly Mrs. L used to tap dance, and has a sense of rhythm. She also had no difficulties when it comes to identifying the sounds of the environment around her, but she’s completely unable to identify musical sounds.

To her, opera sounds like nothing more than a bunch of people screaming on the stage . Her condition, it seems, is quite specific to musical phenomena.

Dystimbria

Oliver Sacks identifies Mrs. L’s condition as that of ‘dystimbria’, a specific variety of amusia where the sufferer’s ability to identify musical stimuli is greatly impaired, and often absent.

This is replaced with the sense that one is listening to nothing more than some kind of noise – as far from music as you could possibly get!

Screaming on stage - Opera?

Congenital Tone-Deafness

In 2002, Isabelle Peretz and her colleagues at the University of Montreal in Canada discovered that in many cases people can be born with amusia, and that it may not necessarily arise from brain damage that occurs after birth.

One particular case study they investigated was that of ‘Monica’, a lady in her early forties who had major problems when it came to pitch discrimination. Peretz played a selection of pitches to Monica, each one different from the last, whether higher or lower.

If the note played was lower than the previous one, Monica was simply unable to hear a difference, but she was slightly better when the shifts were dramatic (such as from a low note to a very high note).

‘Focal Dystonia’

Of particular relevance for brass players is the case of ‘focal dystonia’. The condition, investigated by Eckart Altenmuller over the last decade or so, is the result of problems with the ‘sensorimotor cortex’ in the brain. It is here that various ‘maps’ of the body can be found.

Usually, various parts of the body are represented in the brain in their own distinct areas so the brain can send clear signals from the sensorimotor cortex when we wish to move. Each finger, for example, has its own distinct map in this cortex, which enables us to move a single finger in a complex way at any given time.

Sufferers from focal hand dystonia are often unable to do this.

The separate ‘maps’ in their brains for each finger have started to overlap with one another, making it extremely difficult to execute complex finger patterns on their instrument. This problem is generally specific to a single task, and often doesn’t affect others.

Obsession

The problem is often acquired when musicians, who can often be extremely ambitious and devoted to their practising, try to correct long-standing problems in a sudden burst of creativity.

It is most common among those with perfectionist, and often obsessive musical personalities. A pianist, for example, may try practising a particular scale constantly, only to find that they lose control over one of their fingers, and become unable to send signals to it.

This can often get worse if the subject continues to practise, and can spread to other fingers, rendering the subject unable to play things they’ve been able to play for years.

Schumann

Manic Depression

There’s always been a link between creativity and severe depression. Schumann (above), for example, was a manic depressive, and this had a profound impact on his compositional output. Sufferers from manic depression tend to alternate between periods of ‘mania’ (where the mood is significantly elevated) and periods of depression (where they are often suicidal). Schumann’s compositional activity was directly affected by this disorder.

In both 1833 and 1854 he suffered episodes of depression and attempted to commit suicide. Schumann wrote 2 pieces in 1833 and nothing in 1854, whereas in 1840 and 1849 (‘hypomanic’ years), he wrote around 50 pieces in total.

Andy Billups

New Area

Scientific research is revealing a great deal not just about musical skills and their localisation in the brain, but also the ways in which things can go wrong and the effects that this can have.

We now know that tone-deafness may be a neurological condition, and that people who were once referred to as ‘idiot savants’ have remarkable musical skills that any musician would be envious of.

Science can now explain why famous guitarists like Billy McLaughlin and Andy Billups (otherwise known as ‘Ms Zsa Zsa Poltergeist’ of ‘The Hamsters’ - above) simply had to give up playing because of a lack of finger control, and how music can cause people to have some of the most intense seizures possible.

Stay tuned for more music and science!

Next time: ‘The Science of Music Teaching’.

Chris Davies

Footnotes:

Jourdain, R., Music, the Brain, and Ecstasy: How Music Captures Our Imagination (New York: Morrow & Company Inc.), 199.

Sacks, O., Musicophilia (Picador, 2007), 27.

(Ibid), 107.

(Ibid), 105.

Read Part 1 of this series:

‘The Musical Brain: A Brief Introduction’

A bit more about Chris Davies:

Chris Davies is a postgraduate at the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama, and is currently playing horn with the Cory Band. He graduated from Oxford University in 2009 with a ‘first’ in music, is an Associate of Trinity College London, and a Licentiate of the Royal Schools of Music.

He’s currently involved in a research project at the biosciences department at Cardiff University with Dr. Alan Watson and Kevin Price (Head of Brass at the RWCMD), studying breathing strategies in music performance. He studies tenor horn with Owen Farr, is a composer and a conductor.