|

The World's Greatest Cornet Player?

September 2003 sees the 135th anniversary of the birth of Herbert

Clarke, possibly the most famous cornet player the world has ever

seen and heard.

HERBERT

LINCOLN CLARKE was born on September 12, 1867 in Woburn, Massachusetts,

one of five sons to Eliza and William Horatio Clarke, themselves

descendants of early settlers of Plymouth, Massachusetts. Herbert’s

father was a versatile and competent musician who devoted the majority

of is expertise to the organ and composition. Three of Herbert’s

brothers, Will, Edwin, and Ernest, excelled in musical studies,

and both Edwin and Ernest performed at a professional level on cornet

and trombone, respectively. In Herbert’s early years the Clarke

family moved to Ohio, Indiana, back to Massachusetts, and at 12

years of age to Toronto, Ontario, as his father assumed various

positions as church organist, organ builder, and teacher. HERBERT

LINCOLN CLARKE was born on September 12, 1867 in Woburn, Massachusetts,

one of five sons to Eliza and William Horatio Clarke, themselves

descendants of early settlers of Plymouth, Massachusetts. Herbert’s

father was a versatile and competent musician who devoted the majority

of is expertise to the organ and composition. Three of Herbert’s

brothers, Will, Edwin, and Ernest, excelled in musical studies,

and both Edwin and Ernest performed at a professional level on cornet

and trombone, respectively. In Herbert’s early years the Clarke

family moved to Ohio, Indiana, back to Massachusetts, and at 12

years of age to Toronto, Ontario, as his father assumed various

positions as church organist, organ builder, and teacher.

Clarke’s early musical instruction as on violin, and at 13

years of age he was a second violinist in the Philharmonic Society

Orchestra of Toronto. About the same time he began to play his brother

Ed’s cornet and was soon earning fifty cents a night playing

in a restaurant band, subsequently playing in the Queen’s

Own Regimental Band as well. This early involvement was diverted

when a bout with pneumonia left Clarke unable to practice and confined

to home for several months. After his graduation from high school

n June of 1884, the Clarke family again moved to Indianapolis, save

Will, who remained to continue his employment at a Toronto department

store.

While at Indianapolis, Herbert’s thoughts again turned to

cornet playing. One of the major catalysts to this end was Walter

Rogers, two years Clarke’s senior, who was already active

in the musical life of the city. Clarke admired Rogers’ abilities

on the cornet and the two became fast friends and musical associates

for the remainder of their years. In addition to playing duets,

the formed the Schubert Brass Quartet, adding Herbert’s brothers

Ed on alto horn and Ernest on trombone. Rogers, an accomplished

violinist, also gave Herbert lessons on Viola.

After months of saving, Clarke purchased a Boston “three-star”

cornet, and after more frugality was able to have it silver plated

through a local jewelry store. Upon redeeming the cornet he was

distressed to find that the buffing of the bell had resulted in

flat spots thereon. Regardless of his disappointment he continued

his musical endeavours and succeeded Rogers as first cornetist in

England’s Opera House Orchestra when his friend accepted a

position with Cappa’s Seventh Regiment Band of New York.

Salaried $15 Per week, no meagre wage for the time, Clarke seemed

launched upon his musical career. Shortly after assuming the post,

however, brother Will offered Herbert a job as errand boy in Toronto,

and Clarke’s parents, who were hesitant regarding Herbert’s

professional ambitions in music, persuaded him to accept. Now salaried

at $10 per month, Herbert attempted to adjust to the business world

while still performing when opportunities presented themselves.

Discontent with his wages and sorely missing his active musical

involvement, he requested a raise at the store and when same was

not forthcoming he returned to Indianapolis to play viola in the

Opera Orchestra at his former wage of $15per week.

During the off-season, Clarke performed with the When Clothing

Store Band. The band entered a contest on October 10, 1886 at Evansville,

Indiana, and Herbert entered the solo contest that afternoon. Clarke

relates in his autobiography:

Then in the afternoon came the cornet contest and my application

having been duly sent in I was chosen to play first. The fact that

we had won first prize in the band contest of the morning gave me

more confidence and courage than usual, and then too, the boys in

our band ‘rooted’ strongly for me which added to my

courage. The solo I had chosen was The Whirlwind Polka by Levy,

the same I had played in Canada the previous year at the time I

won the cup. After finishing the long cadenza at the beginning of

the piece I was some-what in a trance although not nearly so nervous

as on my previous occasion when I had played that number. My technique

had improved and I was not any longer the least bit afraid of the

high notes. The tip I had received from Will Mason concerning ‘brilliancy’

had its effect. Nevertheless, I was glad when it was all over. Although

the boys complimented me upon my efforts, I realised that my playing

was far from being satisfactory to myself: I had not played nearly

as well as I would have been able to play had I been in my room

all alone.

After my solo, I left the bandstand and walked to the rear of the

great audience in order that I might listen to the other contestants.

The next soloist in line to play stood up, I think his choice was

the Lizzie Polka by John Hartman and there is no question but that

he played well. I knew every note of the solo and I had to admit

that is style was splendid: quite brilliant as should be that of

a virtuoso. I felt that he surely must win the prize. This thought

affected me to such an extent that I did not wait to hear the finish

of his selection but went some distance off into the woods (the

fairgrounds where we played were on the outskirts of the city),

feeling the most disconsolate boy in the world. I knew our band

boys were set on my carrying away the prize and should I lose it

could never face them again. From the way the other fellow played,

at any rate as far as I had listened, I knew that his performance

was far superior to mine.

I must have been there fully an hour meditating on how I could

get back to Indianapolis all alone feeling discouraged, broken-hearted,

and one of our boys finally after looking everywhere had told me

to hurry to the bandstand as the judges were waiting to present

me with the prize! Imagine my surprise (and secret delight) upon

hearing the good news although I felt sorry for the other fellow

who really played well. A few moments ago I had been contemplating

suicide in its less painful forms. I could not understand my good

fortune. I cannot remember the name of the player who lost to me

and I have never heard of him since – I believe he came from

Brazil, Indiana. I was told later that although he began his solo

in a fine manner playing well throughout until nearing the end he

eventually caved in and made a bad finish.

On reaching the bandstand I was greeted with a degree of applause,

which almost staggered me – I had to be led up to the judges.

One of these made a nice speech complimenting me on my playing and

stating that I had won first prize. Turning around he introduced

me to dear old Henry Distin, a celebrated instrument maker, who

coming forward and shaking me by the hand then presented me with

the award, a baby cornet, one of his own make – the smallest

B-flat cornet ever made measuring only 6½ inches long, 5

inches high with an oval bell and gold plated and elaborately engraved.

Mr Distin, enthused over my playing as being remarkable for a boy,

asked me to play some suitable song on the small instrument. Again,

completely staggered and unable to open my mouth in response, I

took the cornet and endeavoured to play it. I was astonished by

the power possessed by the miniature instrument: it made a hit with

everyone, both audience and bandsmen. It was the only one of its

kind that Henry Distin ever made, and I still have it by me, a carefully

cherished possession.

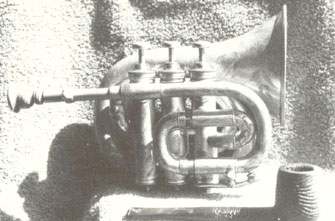

Pocket cornet in B flat made by Henry Distin and won in a cornet

contest by Clarke plating Levy's Cornet Polka in 1886

The euphoria was short-lived, however, for upon returning to the

opera house for the next season it was discovered that the management

planned to replace the violin (Edwin) and viola (Herbert) positions

with a piano. The orchestra went on strike and supported Ed and

Herbert to the end that the whole ensemble was ultimately fired.

Mr. T.R. Brush of the When Clothing Company formed the Alliance

Orchestra and Swiss Bell Ringers in an attempt to save the day,

but after a short tour financial woes overtook the enterprise and

the group disbanded leaving Herbert and Ed both unemployed.

Disheartened, the young cornetist joined his parents in Rochester,

New York, seeking yet another business opportunity. After weeks

of unemployment, Clarke joined the Academy of Music Theatre Orchestra

on viola and played variety shows. He was able to play cornet in

a band drawn from the pit orchestra, to play solos at Ontario Beach,

and other miscellaneous engagements.

Finally the offer of Clarke’s first fully professional position

s a cornet soloist with a yearly salary arrived with an invitation

to join the Citizen’s Band of Toronto under the direction

of an old friend, John Bayley. Accepting the opportunity, Clarke

entered upon a whirlwind musical life which found him performing

with the band plus the Philharmonic Society and the Claxton Music

Store Orchestra, teaching violin at the Trinity College at Port

Hope, maintaining a large class of cornet pupils and conducting

both a band and an orchestra. In addition, he studied harmony and

composition and began to compose and arrange in serious manner.

In the meantime, Ernest Clarke had attained a trombone position

with the famed Patrick Gilmore Band, and when a solo cornet vacancy

occurred in that organization he encouraged Herbert to audition.

Herbert did, and after gruelling and lengthy interview, was named

to the position. At last engaged in the finest musical circles,

Clarke toured with the group for several months.

The

untimely death of Gilmore in September of 1892, however, left Clarke

unemployed, and he returned to New York City where his friends Walter

Rogers, still with Cappa’s Band, assisted him in securing

free-lance engagements. A call from John Philip Sousa brought Clarke

to that illustrious organization as solo cornetist in 1893. Despite

the long tenure which Clarke enjoyed with Sousa, the latter was

unable to afford is musicians full-time employment, and this allowed

Clarke to perform intermittently with the bands of Frederick Innes

and the reformed Gilmore Band under Victor Herbert. The

untimely death of Gilmore in September of 1892, however, left Clarke

unemployed, and he returned to New York City where his friends Walter

Rogers, still with Cappa’s Band, assisted him in securing

free-lance engagements. A call from John Philip Sousa brought Clarke

to that illustrious organization as solo cornetist in 1893. Despite

the long tenure which Clarke enjoyed with Sousa, the latter was

unable to afford is musicians full-time employment, and this allowed

Clarke to perform intermittently with the bands of Frederick Innes

and the reformed Gilmore Band under Victor Herbert.

Two temporary engagements during this period of a different nature

were that of second trumpet in the New York Philharmonic and slightly

later as principal trumpeter of the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra.

In the first of these engagements Clarke used the cornet while in

the second he temporarily adopted the trumpet.

The years from the turn of the century until 1921 found Clarke

continuing to perform, testing cornets for the Conn Company in Elkhart,

Indiana, beginning to write his four instructional methods for cornet

(Elementary Studies, Setting Up Drills, Technical Studies, and Characteristic

Studies), and most importantly, recording extensively. He was by

now playing largely his own compositions, and these likewise comprise

the majority of his records. In several instances, he recorded his

own compositions repeatedly: Bride of the Waves five times, Sounds

from the Hudson twice, and Carnival of Venice twice. Regarding the

Sounds from the Hudson, Clarke had completed the composition while

on a return voyage from England with Sousa and had named the selection

Vase Brilliante. While waiting to dock at New York, however, Clarke

changed the name to Sounds from the Hudson at the suggestion of

Mr. Sousa.

He twice recorded the Russian Fantasie of Jules Levy, Clarke’s

childhood idol, and by the same composer the Whirlwind Polka, long

a staple in Clarke’s repertory. Although Clarke’s name

is generally associated with technical virtuosity, he also recorded

and performed many purely melodic selections. Ah! Cupid by Victor

Herbert conforms to this category and is included on this album.

In addition to the solo recordings, he made several for duet, trio,

and quartet as well, involving other leading brass players of the

day including Walter Rogers, Hermann Bellstedt, and the famed trombonist

Arthur Pryor.

Clarke, who had observed Jules Levy playing after his prime, resolved

not to follow suit and said that he would retire from extensive

concertizing at the age of 50 regardless of his degree of success

at the time. While he did occasionally record and perform after

age 50, he began to concentrate on conducting and teaching, opening

his own school or cornet playing in Chicago. In addition, a long

friendship with the trombonist instrument maker, Frank Holton, developed

a collaboration resulting in the Holton-Clarke cornet.

While

pursuing this diverse livelihood he was invited to become permanent

conductor of the Anglo-Canadian Leather Company Band of Huntsville,

Ontario. The Membership was comprised of employees of the company

though Clarke was allowed to import former associates including

Walter Rogers to upgrade the calibre of the band. In 1921, while

visiting his brother Ernest in New York, he made his last commercial

recordings and performed a few solos in the Milwaukee area with

Holton’s band. While

pursuing this diverse livelihood he was invited to become permanent

conductor of the Anglo-Canadian Leather Company Band of Huntsville,

Ontario. The Membership was comprised of employees of the company

though Clarke was allowed to import former associates including

Walter Rogers to upgrade the calibre of the band. In 1921, while

visiting his brother Ernest in New York, he made his last commercial

recordings and performed a few solos in the Milwaukee area with

Holton’s band.

In 1923, doctors felt that the health of Mrs. Clarke, Lillian (Hause

1872 – 1930), was being adversely affected by the inclement

weather in Ontario. Released from obligations in Huntsville, he

moved to Los Angeles intending to teach cornet but was approached

in October of that year by the city manager of Long Beach regarding

the possibility of conducting the Long Beach Municipal Band. Accepting

the offer, Clarke conducted the aggregation until 1943, performing

only rarely with them, and then, not the virtuoso repertory of his

youth. Following a two year decline in health, Herbert L. Clarke

died on January 30, 1945 in Long Beach. In accordance with Clarke’s

wishes, he was buried next to his wife in the Congressional Cemetary

in Washington, D.C. – near the grave of his lifelong friend,

John Philip Sousa. His musical instruments, manuscripts, and memorabilia

joined those of Sousa in the Department of Bands at the University

of Illinois. This resulted through te influence of A. Austin Harding,

then Director of Bands at Illinois and longtime personal friend

of both Clarke and Sousa.

From surviving recordings, it may be documented that Clarke brought

a refinement of style to the art of cornet solo playing which had

not been fully achieved by his predecessors. While earlier players

articulated harshly and were primarily concerned wit technical display,

Clarke maintained a lyricism and melodic flow, even in extremely

difficult technical passages.

Thus far, the major emphasis of these notes has been the life and

lasting influence of one person, Herbert L. Clarke. However, it

is only recently that 20th Century listeners have approached the

19th century virtuoso solo at all. In this instance, while Clarke

was a tour de force, it is crucial to realise that he is and was

the tour de force of a whole musical phenomenon. Contemporaries

of Clarke who enjoyed if not equal at least competitive prominence

included Herman Bellstedt, Del Staigers, Edwin Goldman, Walter Rogers,

Frank Simon, and Walter Smith, all cornetists who, alongside Clarke,

were but major figures in a large musical tapestry.

Credits:

These notes were made by Gerald R. Endsley for the release of the

LP entitled “Herbert L. Clarke with the Sousa Band and the

Victor Orchestra produced by Crystal Records in 1979. In was also

produced in association with the International Trumpet Guild.

Crystal Records were based at the time of the recording at 2235

Willida Lane, Sedro Woolley, Washington. USA 98284.

Many thanks to Sian Pocknell who took the time to produce the article

from the original for 4BR.

© 4BarsRest

back

to top back

to top

|

|